Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Photo credits on .

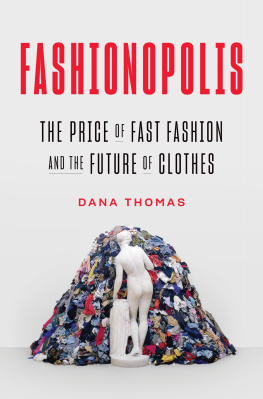

Names: Thomas, Dana, 1964 author.

Title: Fashionopolis : the price of fast fashion and the future of clothes / Dana Thomas.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019019278 (print) | LCCN 2019022421 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735224018 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780735224025 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Clothing tradeMoral and ethical aspects. | Clothing tradeTechnological innovations. | Sustainable development.

Classification: LCC HD9940.A2 T46 2019 (print) | LCC HD9940.A2 (ebook) | DDC 338.4/7688dc23

Introduction

W HEN A MERICAN First Lady Melania Trump traveled to visit migrant children in a Texas detention center in 2018, she was enrobed in an olive-drab anorak by the Spanish fast-fashion retailer Zara, with these words scrawled, graffiti-like, in white, on the back:

I REALLY DONT CARE, DO U?

Pundits opined that the jacket broadcasted how Mrs. Trump truly felt about the locked-up kids. Or her public duties. Or her marriage. Her husband tweeted that it was her view of the Fake News Media. Her spokeswoman claimed: There was no hidden message.

She was right, in a sense. The message was loud and clear. And its a devastating reflection of how we live now.

The jacket was, in effect, the most existential garment ever designed, made, sold, and worn.

Zara is the worlds largest fashion brand. In 2018, it produced more than 450 million items. Its parent company, Spain-based Inditex, reported 25.34 billion, or $28.63 billion, in sales for 2017, of which Zara made up two-thirds, or approximately $18.8 billion.

The jacket, which came from the companys Spring-Summer 2016 collection, retailed for $39. To be able to sell clothing that cheaply and still reap a sizable profit, production is outsourced to independently owned factories in developing nations, where there is little or no safety and labor oversight and wages are generally poverty level, or lower.

At the time workers were cutting and sewing Mrs. Trumps jacket, Amancio Ortega, the octogenarian cofounder and former chairman of Inditex, was the second-richest person in the world (after Bill Gates), with a net worth of $67 billion.

The jacket itself was made of cotton. Conventionally grown cotton is one of agricultures most polluting crops. Almost one kilogram (2.2 pounds) of hazardous pesticides is required to grow one hectareor two and a half acresof the fluff.

It was dyed and lettered with coloring agents that, while decomposing in landfill, would poison the earth and groundwater.

On averageaveragethe piece would be worn seven times before getting tossed. Though given the criticism hurled at Mrs. Trump for donning it on that visit, she would likely never put it on again. So, like most clothing today, to the dump the jacket would go.

I really dont care, do you?

E ACH DAY , we wake up and pose an elemental question:

What am I going to wear?

Much thought goes into the decision: How do I feel? Whats the weather? What do I have to do? What do I want to say? To project?

Clothes are our initial and most basic tool of communication. They convey our social and economic status, our occupation, our ambition, our self-worth. They can empower us, imbue us with sensuality. They can reveal our respect, or our disregard, for convention. Vain trifles as they seem, Virginia Woolf wrote in Orlando, clothes... change our view of the world and the worlds view of us.

As I sit here and write this, Im wearing a black cotton jersey dress with a white pointed collar and shirt cuffs, made in Bangladesh. I spotted it on a Facebook ad, clicked through, and within days it was delivered to my home. It is flattering and fashionably on point. But did I think hard about where it came from when I ordered it? Did I consider why it only set me back thirty bucks? Did I need this dress?

No. No. And nope.

I am not alone.

Every day, billions of people buy clothes with nary a thoughtnor even a twinge of remorseabout the consequences of those purchases. In 2013, the Center for Media Research declared that shopping was becoming Americas favorite pastime. Shoppers snap up five times more clothing now than they did in 1980. In 2018, that averaged sixty-eight garments a year. As a whole, the worlds citizens acquire 80 billion apparel items annually.

And if the global population swells to 8.5 billion by 2030, and GDP per capita rises by 2 percent in developed nations and 4 percent in developing economies each of those intervening years, as experts predict, and we dont change our consumption habits, we will buy 63 percent more fashionfrom 62 million tons to 102 million tons. This is an amount, the Boston Consulting Group and the Global Fashion Agenda report, that would be the equivalent of 500 billion T-shirts.

All this is by design. In airports, you can pick up an entire new wardrobe on the way to the gate. In Tokyo, you can score a tailored suit from a vending machine. Love that outfit on Instagram? Click-click, and its yours. Walk into a fashion store: techno thumps; surfaces gleam; the light is desert-sharpah, the better to see the abundance of offerings. A freneticism sets in. Price, curiously, becomes moot. Youre so beguiled, and so overstimulated, you forget to consider such fundamentals as quality. Its like a sex shop, a former fashion magazine editor mused as we discussed it over lunch in Paris one day. Or a Vegas casino, I countered. You spend freely, recklessly even, and though youve probably been rooked, you feel like youve won.

The expectation is to keep up with the ever-changing trends[to] respond to the constant noise that says, Come buy something else, Dilys Williams, director of the Centre for Sustainable Fashion at the London College of Fashion, told me. The original, pre-industrial definition of fashion was to make things togethera collective that is a convivial, sociable process we use to communicate with each other. The current definition is the production, marketing, and consumption of clothesan industrialized system for making money.