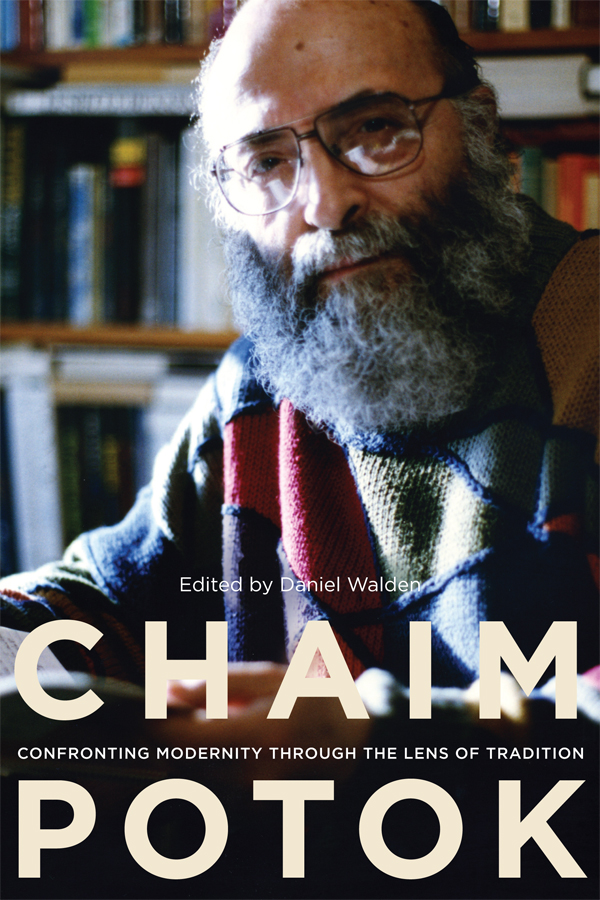

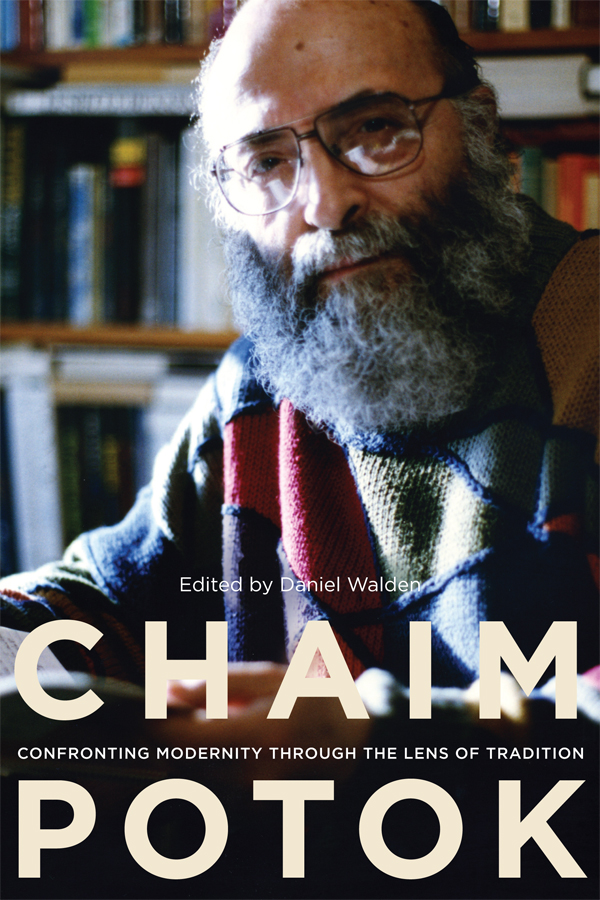

CHAIM

POTOK

Edited by Daniel Walden

CHAIM

CONFRONTING MODERNITY THROUGH THE LENS OF TRADITION

POTOK

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS

UNIVERSITY PARK, PENNSYLVANIA

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chaim Potok : confronting modernity through the lens of tradition / edited by Daniel Walden.

p. cm.

Summary: A collection of essays exploring the work of Jewish American novelist Chaim Potok, with emphasis on his efforts to reconcile the appeal of modernity and the pull of traditional JudaismProvided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-271-05981-5 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Potok, ChaimCriticism and interpretation.

2. Judaism and literatureUnited StatesHistory20th century.

3. Jewish fictionHistory and criticism.

4. Jews in literature.

5. Modernism (Literature).

I. Walden, Daniel, 1922 .

PS3566.O69Z63 2013

813.54dc23

2013002342

Copyright 2013 The Pennsylvania State University

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 16802-1003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material,

ANSI Z39.481992.

This book is printed on paper containing 30% post-consumer waste.

For my wife,

lover, friend, and rock for

fifty-six years, Bea Walden (19272011).

And for my children, grandchildren, and

great-grandchildren.

CONTENTS

The Three-Pronged Dialectic: Understanding Conflict

in Potoks Early Fiction

I would like to thank all those who worked with me for more than thirty-six years to make Studies in American Jewish Literature the great journal it became, and to acknowledge that that work helped prepare me for this volume on Chaim Potok. I wish to thank the contributors to this book, who stayed with me through the years. I also thank all those at the Pennsylvania State University Press who helped bring this publication to fruition, including director Patrick Alexander, editor-in-chief Kendra Boileau, and manuscript editor Julie Schoelles. I am grateful to Hannah Berliner Fischthal, whose typing ability and emotional support were invaluable. Finally, Id like to express my thanks and admiration for the help Adena Potok has extended and to Chaim Potok for being Chaim Potok.

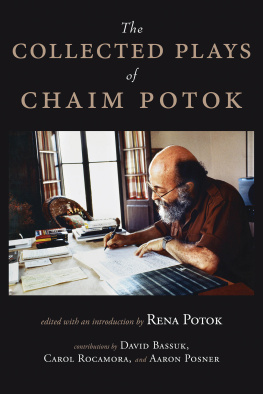

Chaim Potok was a world-class writer and scholar, a Conservative Jew who wrote from and about his tradition and the conflicts between observance and acculturation. With a plain, straightforward style, his novels were set against the moral, spiritual, and intellectual currents of the twentieth century. His characters thought about modernity and wrestled with the core-to-core cultural confrontations they experienced when modernity clashed with faith. Potok was able to communicate with millions of people of many religious beliefs all over the world, because, unlike his major predecessors, he wrote from the inside, inclusively.

Beginning with The Chosen and continuing through The Promise, MyName Is Asher Lev, The Gift of Asher Lev, The Book of Lights, and Davitas Harp, Potok wrote very American novels. They were understandable and attractive to one and all. As , which he resolved by embracing both modernity and observant Judaism. In his view, Judaism was a tradition integrating into the American culture, not opposed to it. He kept his focus on working out his characters identity as American.

Through his novels, Potok was a major voice in American literature because he was the first Jewish American novelist to open up the Jewish experience to a mass audience, to make that world familiar and accessible as the outside world increasingly became willing to acknowledge that Jews are a multiethnic, multiracial, and multireligious people. Potok touched chords felt by many and diverse peoples with his probing and wonderfully written evocations of the world that he knew.

Herman Harold (Chaim Tzvi in Hebrew)

By the time Potok was eighteen or nineteen, as he transitioned from the Hebrew high school to the university, he began to experience a significant change. He came to realize that he and his people were at the core of a subculture in America and that the new and exciting interpretations and ideas he was discovering and experiencing were from the core of the majoritarian culture that he came to call Western secular humanism. Having been formed by his very Jewish world of the Bronx, his encounter with this umbrella culture resulted in his becoming a Zwischenmenschthat is, a between person.

One of the triggers that gave rise to his life as a writer was his discovery of the world of Evelyn Waugh when he was sixteen. Having been raised in a fundamentalist tradition, Potok found that Brideshead Revisited had a galvanic effect on him. I will never forget the effect this book had upon me, he once told me. I found myself in a world of a barest existence of which I knew nothing about before. Brideshead Revisited was about upper-class British Catholics. But, Potok explained, I lived more deeply inside the world of that book than I lived inside my own world for the length of time it took me to read that book. What had Evelyn Waugh done to him? How did a writer, Potok mused, utilizing the faculty of [the] imagination, so fuse words and imagination onto empty sheets of paper that out of that fusion comes a world more real to the reader than the world in which the reader is actually living, his or her day-to-day life? What power there is in that creativity!.

Potok had made contact with modern literature. It is a literature whose practitioners are, by and large, in rebellion against the world that raised them, nurtured them, and taught them their primary system of values. Within that context, Potok attempted to track one element of this confrontation: ideas from the heart of one culture crashing up against ideas from the heart of another culture. He called it a core-to-core confrontation of cultures.

Potok recalled that another trigger occurred while he was serving as an American chaplain in Korea. After visiting the memorial to the dropping of the atom bomb in Hiroshima, Japan, he began to explore the world of Asia through the medium of storytelling. In the strict The teacher sensed rightly, coming from an Eastern European tradition, that Potok had made contact with an element from the umbrella civilization that was inimical to his traditionsomething adversary to the essence of the Jewish tradition he cherished. He was right.

Inherent in the modern literary tradition is a particular way of looking at the world and sensing rightly or wrongly the games that people play, the hypocrisies that enable us to make our way in the world, and the mechanisms that we use to live every day. Potok decided that there were three avenues he might take: break with the tradition that gave him life, give into it, or live in constant tension with it, as he put it in 1982. So he read Joyce, Waugh, OConnor, Mann, Flaubert, Jane Austen, Upton Sinclair, and Mark Twain, even as he studied the Talmud. He was committed to the possibilities of communicating his own narrow world through fiction as objectively as he could, while presenting and exposing Orthodoxy, especially ultra-Orthodoxy, in as critical a way as Waugh had presented Roman Catholicism.

Next page