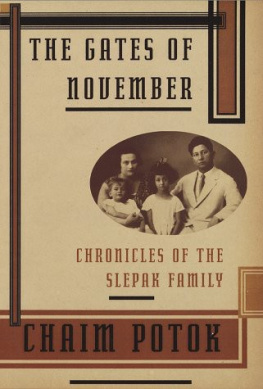

Chaim Potok

The Gates of November

1996

The story of the dissidents in the former Soviet Union is one of the few truly noble astonishments of the twentieth century. Some, like Andrei Sakharov, were of heroic stature even before they chose the path of opposition. Others, like Volodya and Masha Slepak, came to greatness only after they stepped forward. Clearly, all the dissidents could not be present in these pages. It is to each and every one of them that I dedicate this book.

A tedious season they await

Who hear November at the gate.

Alexander Pushkin

History brought together on the same soil two vigorous peoples, Russians and Jews, whose bitter destiny it was to be ruinously at each others throats.

Present-day Russia had its origins in unruly Slavic and Finnish tribes who migrated southward sometime in the eighth century of the Common Era, agreed among themselves to be ruled by a northern tribe known as the Scandinavian Rus (some claim the Rus came as conquerors), and created a state known as Kievan Russia, with Kiev on the Dnieper River as its leading city.

As for the Jews-tombstone inscriptions indicate that there were Jewish communities on the shores of the Black Sea as far back as the third century before the Common Era. In the early centuries of the Common Era, Jews began to flee toward what are now Georgia and Armenia from the persecutions of the Greek Orthodox Church of Byzantium. And there appears to be some truth to the legend that around 740 the pagan kingdom of the Khazars, an Asiatic tribe situated on the shores of the Caspian Sea, converted en masse to Judaism.

Shortly before the year 1000, the Kievan ruler Vladimir formed an alliance with Byzantium and adopted Greek Orthodox Christianity as the official religion of his state. Together, they crushed the Jewish kingdom of the Khazars, whose populace was absorbed into the world of the Kievan Rus.

Along with Greek Orthodoxy, there arrived from Byzantium a new architecture, music, art, churches, a clergy, laws, an educational system-and a hatred of and contempt for the Jew. It was a loathing pure and unmitigated; it suffused the entire Kievan polity, ruler and clergyman and nobleman and serf. It continued for centuries, from the height of Kievan Russias power to its disintegration in civil wars and final conquest by Mongols in 1240; then, untouched by the softening admixture of Renaissance and Reformationist ideas which swept through Europe but barely engaged Russia, it persisted into the Muscovite state, which began its expansion under Ivan III and Ivan IV in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and finally into the dynasty of the Romanovs, founded in 1613.

Demon, ogre, heathen, and killer of Christ-that was how the Russian saw the Jew. The Orthodox empire of Muscovite Russia remained virtually without Jews-until 1772.

In the reign of Catherine II, Poland fell to the three powers surrounding it: Germany, Austria, and Russia. Jews had been living in Poland since the Middle Ages, at the invitation and under the protection of Polish kings and nobles. By 1795 the portions of Poland procured by the distant progeny of the Kievan Rus had brought under the dominion of Muscovite Russia the largest Jewish population in the world.

It is estimated that in 1850 there were about 2,350,000 Jews in Russia. They lived in a restricted region known as the Pale of Settlement: almost a million square miles from the Baltic to the Black Sea; two thousand townlets and cities in twenty-five provinces, the Jews one-ninth of the population. By the close of the nineteenth century Jews in the empire of Russia numbered around 5,000,000.

Official policies toward them vacillated from seeming benevolence to outright cruelty, one tsar granting them rights which the next tsar would withdraw. In essence, the Russians would have preferred that they simply vanish. Tsarist policy was tersely stated in 1895 by Konstantin Pobedonostsev, head of the Holy Synod, the governing body of the Russian Orthodox Church, under Alexander III (reigned 1881-1894), and the tutor of Nicholas II (reigned 1894-1917): One-third will die out, one-third will flee the country, and one-third will dissolve into the surrounding population-by which he meant, will convert.

The response of the Jews to tsarist persecution ran the gamut from an intensification of separateness by religionists to attempts at participation in Russian culture by assimilationists to the joining of the ranks of socialists and revolutionaries by increasingly disenchanted and enraged youth. The government-organized pogroms following the assassination of Alexander II in 1881 bitterly disillusioned many Jews who had chosen the path of assimilation. They began to turn their energies inward-to the revival of Jewish nationalism; to a culture of their own in a Jewish homeland; to the creation of a new literature in Yiddish and in a miraculously reborn and modernized Hebrew.

The rule of the tsars came to an end early in 1917 with the abdication of Nicholas II. Quiescent for three decades following the November 1917 Bolshevik Revolution (October according to the old Julian calendar then still in use in Russia), the rooted Russian hatred of the Jew surfaced in an especially insidious form during Stalins final years and led, ultimately, to the turbulent and fateful events that befell the individuals whose lives are in the pages of this book.

History also brought me into the Russian world of Volodya Slepak and his wife, Masha.

Russia was very much a part of my familys life during my early New York years: detested by my parents in the 1930s; a needed ally during the Second World War; a sudden enemy once again afterward. Russian literature, art, music-intoxicating. Russian power-reptilian. It seemed a vast and sealed dark land, the Soviet Union, and it was only after the death of Stalin and in the aftermath of the Khrushchev years that there began to be heard the thin, small voices of Jews who were still alive behind the Iron Curtain. From books like The Jews of Silence by Elie Wiesel and Between Hammer and Sickle by Ben Ami (pseudonym of Lova Eliav); from the occasional visitor to the Soviet Union; from the diplomats who talked off the record; from the reports of perceptive journalists-from those sources and others came news of a nascent dissident movement inside one of the most repressive of modern states. Certain names began to move into prominence, among them that of the Slepaks. They had applied for exit visas from the Soviet Union in April 1970, had been repeatedly refused, and stood during the seventies at the center of an increasingly vocal and visible dissident movement.

In the early 1970s I lived in Philadelphia, which had become a major center of activity in the struggle to free Soviet Jews. By the late 1970s the rescue of Soviet Jewry was very high on the agenda of world Jewry. What the KGB and the Politburo regarded as a well-organized, sophisticated international network of Jewish smugglers and spies intent upon the destruction of the Soviet Union, Jews knew to be a fragile lifeline made up mostly of ordinary men and women determined to aid a suffering branch of their people.

From time to time I would hear about the Slepaks. It seemed that the constant refusal to grant them exit visas was connected to some kind of secret work in which Volodya Slepak, a highly trained electronics engineer, had once been engaged. There were also rumors that he was being deliberately held back by his father, who, it turned out, had once been high in the ranks of those legendary Bolsheviks who had fathered the Russian Revolution. An Old Bolshevik in the Slepak family! How had he survived the Stalinist purges of the thirties that had cut like scythes through Old Bolshevik ranks?

Next page