Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) was originally developed by Dr. Marsha Linehan to treat chronically suicidal women with Borderline Personality Disorder (Linehan, 1993a, 1993b). Several research studies have demonstrated that DBT reduces suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors, emergency department visits, hospital admission rates and lengths, and levels of depression and anger. To date, DBT in its original and adapted forms is the psychotherapy with the strongest evidence base for this population (Bohus et al., 2004; Carter et al., 2010; Clarkin, Levy, Lenzenweger, & Kernberg, 2007; Koons et al., 2001; Linehan, Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon, & Heard, 1991; Linehan et al., 1999, 2002, 2006; McMain et al., 2009; McMain, Guimond, Streiner, Cardish, & Links, 2012; Verheul et al., 2003).

Most studies of DBT have focused on women, because in clinical settings Borderline Personality Disorder is more commonly diagnosed in women than in men. However, there is preliminary evidence that supports the use of DBT for men with similar problems. DBT has been adapted (Dimeff & Koerner, 2007) for a wide range of difficult-to-treat populations, such as for people with eating disorders, people with substance use disorders, people in correctional settings, suicidal adolescents (Miller, Rathus, & Linehan, 2007), people with treatment-resistant depression, and people with intellectual disabilities.

Overall, DBT and its adaptations are designed for people with complex, severe problems who engage in impulsive and self-damaging behaviors in response to overwhelming emotional dysregulation. DBT targets the combination of emotional dysregulation and impulsive behavior, which is a hallmark of Borderline Personality Disorder but also occurs in other circumstances, particularly when several challenging disorders co-occur. Problems that are associated with emotional dysregulation and behavioral impulsivity can be addressed independently of diagnostic labels; therefore, in practice it is probably not essential to have a particular diagnosis in order to offer DBT or to integrate DBT techniques into other approaches.

In this introductory section, we provide a brief overview of DBT and then discuss some concepts and techniques from it that may be integrated into general psychotherapeutic treatment when it is not possible to provide the full model. Research is currently under way to examine whether specific elements of DBT are effective in the absence of the full treatment package. To date, there are preliminary data supporting the use of DBT skills training on its own (Soler et al., 2009), as well as selected DBT-informed principles or strategies (Turner, 2000).

STRUCTURE AND THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

Treatment Modes and Their Functions

In its standard outpatient format for the treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder, DBT consists of four concurrent modes of treatment delivery: weekly individual therapy, weekly group skills training, between-session phone coaching, and weekly therapist-consultation team meetings. In standard DBT programs, clients receive these four components in an outpatient setting over the course of 1 year.

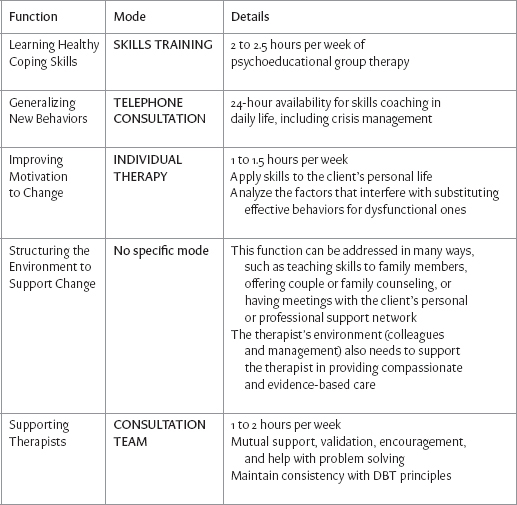

Successful treatment for complex, multidisordered individuals with emotional dysregulation must fulfill five functions: learning new skills, generalizing new behaviors, improving motivation to change, ensuring the individuals environment supports change, and supporting therapists. Each of the four DBT treatment modes addresses one of these functions. In addition, various family or social network-oriented interventions may be used to assist individuals in shaping their environments to reinforce desired changes and avoid reinforcing problematic behaviors (see Table 1).

Table 1. Functions and Modes of Dialectical Behavior Therapy

Adapting DBT for inpatient, residential, or day treatment settings requires finding creative ways to ensure that these functions are fulfilled (for information on DBT adaptations, see Dimeff & Koerner, 2007). In fact, anyone wishing to provide effective assistance to a person with severe emotional dysregulation should keep all five functions in mind and devise a treatment plan that addresses them as well as possible. Some settings may not be able to provide a skills group, for example, but an individual therapist may be able to incorporate teaching skills into individual treatment sessions. If couples counseling is not available, an individual therapist may be able to work on interpersonal skills to improve relationships within a clients social network. If 24-hour phone coaching is not available, perhaps coaching calls could be taken during more limited hours, or the therapist could help the client teach a friend or family member how to offer effective skills reminders during a crisis.

Theoretical Basis of DBT

DBT evolved out of Linehans efforts to apply Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to women who have histories of chronic self-harm and suicidality. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is informed by Learning Theory, from which one can extract three fundamental principles:

learning may be conditioned by association (classical conditioning),

learning may be reinforced by consequences (operant conditioning), and

learning may occur through observing others (modeling).

Linehan discovered that Cognitive Behavioral Therapys focus on change, including efforts to correct thinking errors, was experienced by clients as invalidating, which led to an increase in anger and therapy dropouts. She felt that the emphasis on change needed to be balanced by an emphasis on acceptance. To find this balance, she incorporated features of Rogerian client-centered therapy, Western contemplative practices, and especially Zen mindfulness into the treatment.

Next, in order to integrate these two oppositeschange and acceptanceLinehan borrowed from dialectical philosophy, which describes the process of combining elements from opposing poles in order to form a creative synthesis.

Thus, the three theories that inform DBT are the following:

Learning Theory, with its emphasis on identifying all the variables that promote or hinder change;

Zen philosophy, with its emphasis on accepting each moment as it is; and

Dialectical philosophy, which emphasizes that reality is composed of apparent opposites and which proposes searching for ways that two opposing ideas can both be true.

DIALECTICAL BEHAVIOR THERAPY: SELECTED TECHNIQUES

In the accompanying DVD and learning guide, we describe two techniques to help therapists maintain compassion for clients with severe emotional dysregulation, as well as four sets of strategies that may be used in individual sessions with clients. For a complete description of all therapist strategies in DBT, therapists should refer to the treatment manuals Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder (1993a) and Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder (1993b) by Marsha Linehan.

The Biosocial Theory and Assumptions About Clients

Zen philosophy emphasizes the value of a nonjudgmental and compassionate attitude. It is essential that clients learn to be nonjudgmental and compassionate toward themselves, and that therapists adopt similar attitudes toward their clients. Compassion may be defined as being empathic toward anothers suffering and wanting to help. A compassionate approach does not have to be unfailingly soothing and supportive: at times, an empathically derived wish to help can require confrontation. Nonetheless, negative emotions such as frustration or anger must be expressed in a way that is genuine yet avoids being hostile or rejecting.

Next page