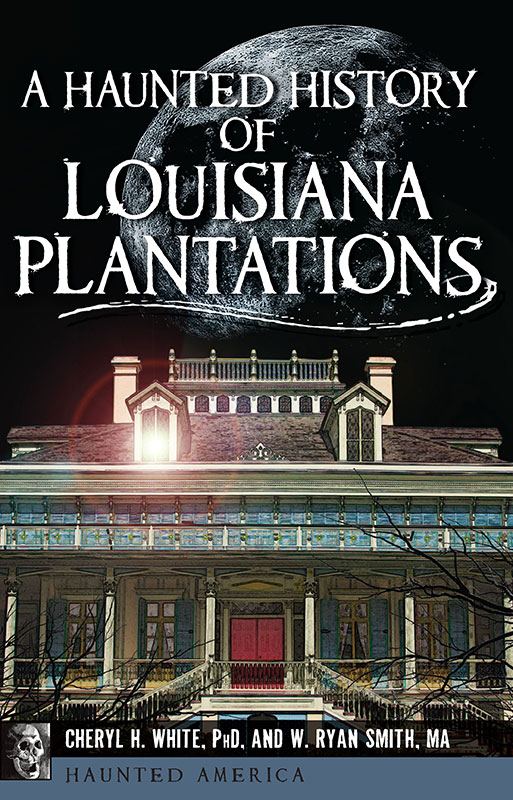

Published by Haunted America

A Division of The History Press

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2017 by Cheryl H. White and W. Ryan Smith

All rights reserved

First published 2017

e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978.1.62585.402.5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017940958

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.875.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are many people, places and agencies that helped make this work possible and to whom we owe special gratitude. Thanks to the history majors and graduate students of Louisiana State University at Shreveport, especially Mitchell Baxter, Ashley Dean, Catherine Green, Joanna Hunt and Ciara Mathis. A special thanks also goes to Bess Maxwell and Connie Williamson of Louisiana Spirits for their assistance with some of the paranormal aspects of this book.

Much gratitude is owed to the people interviewed for this work in gathering the oral histories, legends and folklore of these beguiling Louisiana plantations, including Mr. Dustin Fuqua, Judge Henley Hunter, Mr. Tommy Whitehead, Mr. Jim Blanchard, Mr. Kevin Kelly and those tour guides we will forever know by first name only. They gave the most precious resource possible for our sake: their own time.

There are also institutions that merit acknowledgement, including Cane River Creole National Historical Park, the Association for the Preservation of Historic Natchitoches, the San Francisco Plantation Foundation and the River Road Historical Society. The Noel Library at Louisiana State University at Shreveport provided resources and inter-library loan support, as did the library of Tulane University in New Orleans.

We are grateful to the tireless staff of The History Press, especially our editor, Candice Lawrence.

Finally, we would like to extend a special note of gratitude to mutual friend Father Peter Mangum for making the introduction that began a fun and fascinating collaboration!

CHAPTER 1

IN HOUSES WHICH ARE OLD

A PRIMER TO THE LOUISIANA BIG HOUSE

In houses which are oldthe forms of whose very walls and pillars have taken body from the thoughts of men in a vanished timewe often sense something far more delicate, more unwordable, than the customary devices of the romanticist: the swish of a silken invisible dress on stairs once dustless, the fragrance of an unseen blossom of other years, the wraith momentarily given form in a begrimed mirror. These wordless perceptions can be due only, it seems, to something still retained in these walls; something crystalized from the energy of human emotion and the activities of human nerves. Clarence John Laughlin, author, Ghosts Along the Mississippi

The landscape of Louisiana today is dotted with visible reminders of a long-lost age, particularly in those areas along the old arterial rivers of the state. The age of the great plantation echoes across more than a lifetime of separation, with profound cultural and historical impacts that once wrought the states identity from the primitive colonial past and continue to shape its character today. The fabled antebellum period throughout the Deep South was home to an economic system that would quickly pass into the pages of history, but not without leaving behind a rich and intriguing narrative.

After the Civil War, the plantation estate remained for a timeevolving, flexing, straining but not breaking until it was at last vanquished by mechanized farming through the slow and strangling death of the last great holdouts to the Industrial Revolution. That resulting heritage, this residue of the agrarian country estates, the enslaved families, those peeling faades and crumbling pillars contain a shared memory that perpetuates still. The plantation encounter today is framed within the context of a distinctively original folkloreoccasionally light and interesting, often mysterious and dark but universally compelling. There is in them something at once horrific and grand, something both pure and irreverent, both stately and remote, something uniquely Louisianan.

It is through that colorful lens of haunted folklore that this work seeks to tell some familiar history in a new way. Scattered throughout the plantation chronicles of Louisiana are tales of ghosts said to haunt stately mansions, evidence of lively superstitions of both slave and free populations. There are vestiges of fascinating social reactions indicative of a bygone era, all of which frame a way of life that breathed its last as the cacophony of the petroleum-powered farm-all tore open the alluvium in neatly furrowed lanes. Certainly, there are many footprints through time that shape this particularly unique journey of Louisiana history, most of which are rooted in the very land itself, with both ancient and contemporary cultural influences.

Long before the Europeans set eyes on Louisiana, the vast wilderness of marshy swamps and bayous throughout the south and deep timber forests of the north was home to Paleo-Amerindians. The now-identified major tribes of the Caddo, Tunica, Natchez, Atakapa, Choctaw, Houma and Natchez settled the region millennia before Sieur de La Salle claimed all the lands drained by the great Mississippi River in the name of French King Louis XIV in 1682. There can be no question that their culture, even in assimilation with that of new peoples, would leave an imprint on the future. Throughout much of the French colonial period in Louisiana, the native population far outnumbered the European expatri. Yet with inevitable conquest and colonization, the unique civilizations of these ancient people were threatened to near-extinction. Soon enough, the arrival of the French, Spanish and African peoples would gradually but dramatically transform the subsistence farming and nomadic lifestyles and small-scale farming of the natives into a much larger and commercially successful agricultural economy.

Colonial authorities issued grants of large sections of land in Louisiana (concessions) to people of already distinguished wealth and influence. These earliest Europeans would produce a distinct class known as Creolesthose born in Louisiana of either French or Spanish descentwhile intermarriage with Africans would beget the Creoles of Color. Many people settling in the new territory of Louisiana received smaller plots of land known as habitations, usually only a few acres, which were gradually consolidated by agreement into larger farms. With the passage of time and influence of new technologies, both of these kinds of land grants resulted in the development of what would become a plantation system, distinguished from farms primarily by sheer acreage and gross crop production. These were truly for-profit enterprises. While many people believe that such plantations were always characterized by large stately mansions surrounded by thousands of acres of rich land, this is not really an accurate depiction of the typical planters built environment. Most dwellings were not as grand as popular culture has portrayed them to be, but of those that were, the surviving ones are nothing short of wonders. These houses form the crux of the mystifying landscape of planter society. Louisiana is fortunate to have many diverse examples.

Next page