This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 2013 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

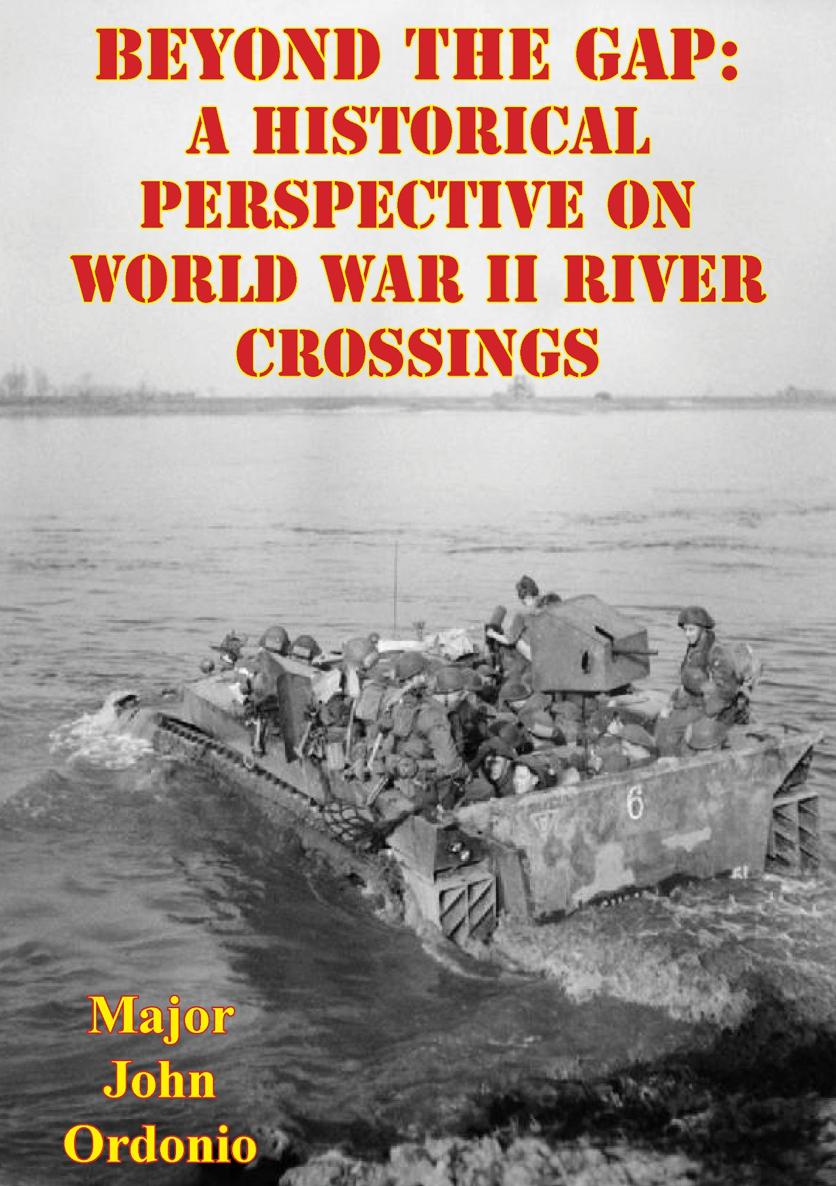

BEYOND THE GAP: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ON WORLD WAR II RIVER CROSSINGS,

By

Major John Ordonio

ABSTRACT

Crossing a river against a defending enemy force is a difficult and complex task for any army. History has shown that preparation is necessary to avoid disasters during this type of operation. In 2003, the Third Infantry Division crossed the Euphrates River because it was prepared for this task and possessed the necessary equipment. Since then, no other divisions or corps has executed river crossing operations.

While the United States Army focused on counterinsurgency operations during the last twelve years, it underwent significant changes to adapt to meet the adversities on the battlefield. It transformed its war-fighting organizations, trained its corps and divisions with computer simulations, and relegated field training to brigade and below units. In addition, its current doctrine now refers to river crossings as the deliberate wet gap crossing. Because of these changes, many questions arose as to the present corps and divisions preparedness to do large-scale operations, to include its ability to plan, prepare, and execute the deliberate wet gap crossing. If called today, could these organizations conduct this complex operation? Examining river crossings in Europe during the Second World War was appropriate for insight into how the previous generation of corps and divisions prepared and executed such a complex task. After analyzing how these units were able to cross the numerous waterways in Europe, the present Army should consider reassessing its doctrine, training, and organization and equipment to prepare its units for future deliberate wet gap crossings.

INTRODUCTION

It was a summer morning in 1944. As the sun rose and embraced the grassy farmland, a distant sound of rolling wheels and rumbling metal suddenly stopped as an army division approached a gushing river that blocked it. Shortly thereafter, dismounted reconnaissance forces emanated from this formation and slowly crept through the open fields searching for enemy presence near this obstacle. Overhead, friendly airplanes circled above, photographing potential crossing points. The enemy defenders, hidden on the other side, protected the far bank with a combination of machine guns, tanks, and artillery. As the division mustered its troops and bridge equipment for the assault crossing, bombers emerged below the clouds and dropped their explosive payloads on heavy bunkers while the artillery struck at hidden enemy armored vehicles with multiple fragmenting shells. As the sun began to set, the division covered its movement by firing white smoke rounds to obscure the enemys view. While the engineers and the infantry troops hauled the inflatable boats and bridge pieces to the crossing sites, the enemy fired desperately through the thick cloud. Under cover, the infantry rowed across the river, leaped out of their assault boats, and took up hasty defensive positions on the far side. With the infantry in position, the engineers pieced together the puzzle of parts, and began emplacing the bridge across the gap. While the engineers worked, the rest of the division slowly made its way towards the embankments through a moonlit maze of roads and checkpoints. Other soldiers, tasked with controlling traffic, met the vehicles at the entrance of each bridge, inspected them, and informed the drivers to move slowly across the spans. By high noon the following day, 2,000 vehicles and 14,000 troops had crossed this barrier and were continuing to advance against the enemys main force. {1}

Crossing a river, defended by an enemy force, is a difficult and complex task for any army organization. It involves many diverse activities, besides physically crossing it and synchronizing many units with different capabilities. One method to visualize the crossing process is to organize conceptually the battlefield into three related parts: the deep area, a close operations zone, and a rear or security area. {2} The activities that take place on the river as the force approaches the crossing area, and on the opposite side once the unit has arrived at its banks is the deep area. In this zone, the enemy force opposes the friendly advance, defends the water line, and provides artillery fire and logistics support for the defenders. It is here where the enemy awaits the crossing units in defensive positions.

As the unit approaches the river, the commander has options to affect his opponent and facilitate the actual crossing. Two of the most important tasks are conducting reconnaissance and attacking the enemy with indirect fires. The overall crossing force commander directs his units to conduct reconnaissance to discover information on the enemy and terrain in the crossing area. {3} Ground organizations, such as patrols and mounted cavalry scouts, probe the hostile defenses. He sends aircraft to photograph and observe the defender as well as identifying potential places to cross the river. They seek good crossing points along the river appropriate for launching assault boats and rafts and then building the bridges. These areas require good routes to and from the crossing site and terrain that allows for covering fire and defending the enclave on the far side. Detailed reconnaissance allows the crossing force to attack enemy positions, headquarters, and supply facilities with indirect fires and aircraft. Indirect fires are those weapons, such as howitzers and mortars, which do not rely on a direct line of sight to aim and fire. Aircraft can find and destroy enemy positions. In addition to the fighters and bombers available in World War II, modern commanders can also utilize attack helicopters and remotely piloted aircraft. Thus, reconnaissance and indirect fires are important in the deep area because they set the conditions for the operation.

It is during close operations that the actual crossing takes place, and it includes all activities conducted on the river. Most important during this phase is protecting the precious crossing equipment. These boats, rafts, and bridges are a limited resource, difficult to replace, and the defenders most important target. Therefore, the first action of the crossing force is to establish a bridgehead on the far side of the river. A bridgehead is the area, on the enemy side, that protects the crossing points. {4} It must be free of enemy presence and be large enough to position anti-aircraft and anti-armor units to contribute to the crossings defense, and provide sufficient space to organize the vehicles as they cross from the friendly side. The bridgehead commander has many tasks during this phase. In the beginning, he organizes the ground troops and engineers into assault forces. These forces traverse the river in boats, defeat the defending enemy, and establish defensive positions. Their primary task is to defend the engineers who are directing the actual crossing. The engineers usually begin the process by moving boats to the river and building rafts. They start to ferry combat vehicles and more troops across to provide more support to the infantry, who continues to attack and clear the area of enemy forces. While the infantry is expanding the bridgehead, engineers and military police set up the routes and checkpoints on both sides of the river to guide the division during the crossing. Once the assault force has secured the bridgehead, engineers begin to build the bridges. When they complete this task, units move towards the river, and pause at certain checkpoints. From here, engineers organized units into crossing groups to regulate the flow of traffic across the bridge, and to ensure they do not congregate on the far side and become a target for enemy aircraft or artillery. When the entire division is on the opposite side, commanders ensure that all units reorganized into their tactical arrays, refueled, and ready to continue the mission.