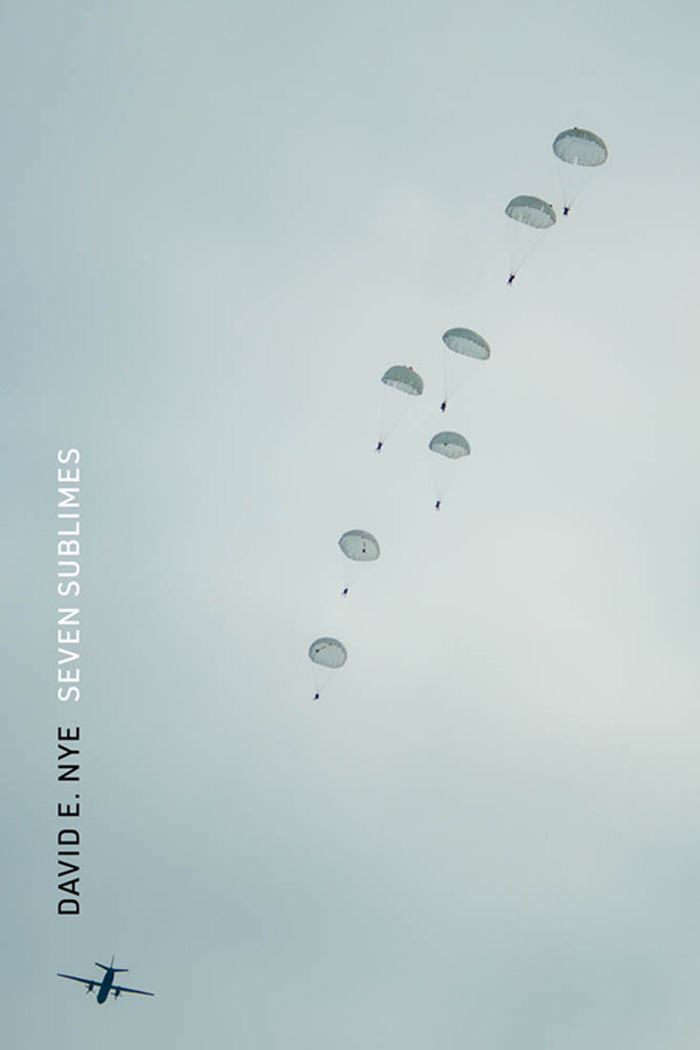

Seven Sublimes

Seven Sublimes

David E. Nye

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2022 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

This book was set in ITC Stone and Avenir by New Best-set Typesetters Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Nye, David E., 1946- author.

Title: Seven sublimes / David E. Nye.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021033922 | ISBN 9780262046923

Subjects: LCSH: TechnologySocial aspectsUnited States. | TechnologyUnited StatesPsychological aspects. | TechnologyUnited StatesHistory. | Sublime, The.

Classification: LCC T14.5 .N933 2022 | DDC 303.48/3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021033922

10987654321

d_r0

Contents

Preface

The sublime is a widely shared emotion that all human beings, regardless of their race, gender, or nationality, are capable of experiencing, for they all are endowed with the same bodily senses. When W. E. B. Du Bois visited the Grand Canyon, the railroads forced him to travel in a segregated railway car because he was Black, but this did not prevent him from appreciating its grandeur. Du Bois declared unequivocally, I believe that all men, black and brown and white, are brothers, varying through time and opportunity, in form and gift and feature, but differing in no essential particular, and alike in soul and the possibility of infinite development. His meditation on the enormous chasm concluded with these words: It is notit cannot be a mere, inert, unfeeling, brute factits grandeur is too sereneits beauty too divine! It is not red, and blue, and green, but, ah! the shadows and the shades of all the world, glad colorings touched with a hesitant spiritual delicacy. Du Bois understood that the capacity to experience the sublime is universal.

This book focuses less on formal philosophy than on personal experiences, such as visiting a national park, skyscraper, disaster site, battleground, or virtual reality. To experience the sublime, it is not necessary to travel to famous locations. During travel restrictions due to the pandemic in 20202021, many people discovered solace and inspiration in local microadventures. They camped in nearby parks; they climbed trees; they disrupted routines; they stared at the night sky; they took walks in unfamiliar places. They discovered that much of the work of cultivating awe is in paying attention to the small details around us. Recent studies confirm what philosophers have long said: confronted with the sublime, people commonly feel a sense of humility. These experiences of awe reduce self-interest and increase social cohesion. The sublime is a powerful individual moment, but it also has cultural effects, helping to hold groups together. This is a useful starting point for an historical assessment of the sublime, considered not as a static category but as an evolving realm of experiences with at least seven distinct forms.

Acknowledgments

In 1994 I thought that my American Technological Sublime (MIT Press, 1994) provided the epitaph for the technological sublime. I was wrong. Instead, for the last quarter century new objects have been considered sublime. This general interest by itself might have prompted me to write a book, but I was spurred on by three invitations. In the fall of 2017, the University of Lodz in Poland invited me to give the keynote address at a conference on the technological sublime. The following year, the journal Azimuth: Philosophical Coordinates in the Modern and Contemporary Age requested a contribution to a special issue, published in 2018 as What Comes after the Technological Sublime? Finally, the journal ISIS asked me to review Alan G. Grosss The Scientific Sublime.

When I talked about writing a study of new forms of the sublime with Katie Helke, my editor at the MIT Press, she immediately encouraged me. Three institutions then helped make it possible. In 2017, the University of Minnesota appointed me Senior Research Fellow in the history of technology, provided a congenial workspace at the Charles Babbage Institute, and granted me access to library and archival resources. At the same time, the University of Southern Denmark allowed me to retain access to its library after retirement. In 2019, I worked out the structure of the project during a summer residency at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in Amsterdam. Three members of its staff were particularly helpful: Trinette Zecevic-Boulogne, Astrid Schulein, and Ruud Van Veen.

Because writing a book is largely a solitary affair, occasional discussions with colleagues were not just helpful but vital. Many offered advice or pointed me to useful materials. At Virginia Tech, Richard Hirsh listened to an account of the project in 2018 and took an interest in its development. At the University of Maryland, Thomas Zeller discussed his work on constructed sublime experiences on scenic highways in Germany and the United States. At the University of Minnesota, Douglas Lewis for half a century has patiently tried to improve my understanding of philosophy, while the late Alan Gross, whom I first met when the project was well along, suggested sources for chapters 4 and 5. At Minnesotas Charles Babbage Institute, Tom Misa and Jeffrey Yost suggested materials that improved chapter 6. My Danish colleagues Jrn Brndal, Thomas rvold Bjerre, Niels Bjerre Poulsen, Anders Bo Rasmussen, and Anne Mrk drew my attention to historical examples. At the University of Munich, Klaus Benesch shared his thoughts on cyborgs and his expertise in literary and cultural history, while Temple Universitys Miles Orvell directed me toward photographic representations of the sublime. Richard Haw shared with me his wide knowledge of New York City and nineteenth-century technology. Years ago, Professors Jeff Bolster and Marty Melosi were senior Fulbright scholars in Odense, and they provided insights into environmental history that proved useful in writing chapter 8. None of these fine scholars, nor the three anonymous peer reviewers selected by MIT Press, are responsible for errors or misconceptions that may remain.

This book is gratefully dedicated to Helle Bugge Bertramsen Nye, who believed in it from the start and endured my talking about it until the end.

Tangible Sublimes

1

Natural

What is it like to experience the natural sublime? Charles Dickens could answer that question based on travel experiences. Arriving at Niagara Falls, he saw first, two, white, great clouds rising up slowly and majestically from the depths of the earth, and coming closer he heard the mighty rush of water and felt the ground tremble underneath my feet. He climbed down the steep bank to the foot of the American falls, deafened by the noise, half-blinded by the spray, and wet to the skin. Boarding a small ferry that crossed the river to the Canadian side, he felt stunned, and unable to comprehend the vastness of the scene, until he stood on Table Rock and was enthralled by the cataracts full might and majesty. He remained at Niagara for ten days, viewing it from every angle and at different times of day. The experience engulfed his senses, and it filled him with a sense of peace, as the strife and trouble of daily life receded from my view. Had Dickens stayed until winter, he might have seen the great falls transformed into a great wall of ice, with water falling behind it (figure 1.1).

Next page