ISBN for this digital edition: 9780-8263-2495-5

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Szasz, Ferenc Morton, 1940

The day the sun rose twice.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Atomic bombNew MexicoLos AlamosHistory.

2. United States. Army. Corps of

Engineers. Manhattan Engineer District.

3. Los Alamos (N.M.)Description.

I. Title.

II. Title: Trinity Site nuclear explosion, July 16, 1945.

QC773.A1S93 1984 623.45119 84-7587

1984 by the University of New Mexico Press

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 847587

ISBN-13: 9780-8263-0768-2

ISBN-10: 08263-0768-X

Preface

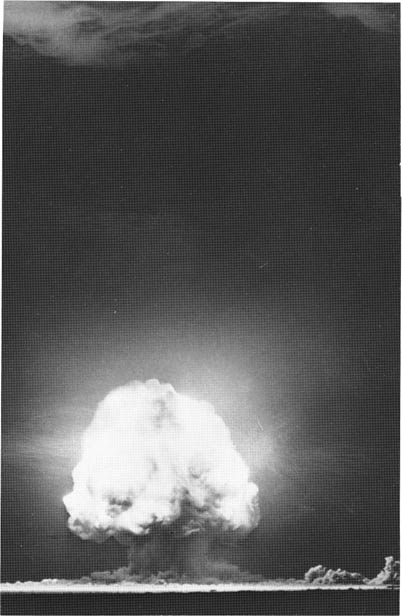

Herman Melville once wrote, To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme. The judgments on the book will be left to the reader, but I have no doubts about the power of the theme. This is the story of the worlds first nuclear explosion. It occurred at 5:30 A.M. on July 16, 1945, about 120 miles from Albuquerque, New Mexico. Its legacy is much in evidence today.

As usual, I am indebted to a great number of people for their aid in the preparation of this study. To begin with, I would like to give special thanks to the archivists and librarians who so patiently replied to my endless stream of requests: Walter Bramlett, Tony Rivera, Bill Jack Rodgers, Elaine Ruhe, Dan Baca, and Alison Kerr of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, New Mexico; Hedy Dunn of the Los Alamos Historical Society; Stanley Hordes and his staff at the New Mexico State Archives and Records Center, Santa Fe, New Mexico; Edward J. Reese of the Modern Military Headquarters Branch of the National Archives, Washington, D.C.; David Warringer and Richard V. Nutley of the Department of Energy, Coordination and Information Center, Las Vegas, Nevada; Mitch Tuchman and Bernard Galm of the UCLA Oral History Program and Anne Caiger of the UCLA University Library, University of California at Los Angeles; Elizabeth B. Mason of the Columbia Oral History Program, Columbia University, New York City; Frances M. Seeber of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, New York; Benedict K. Zobrist of the Harry S Truman Library, Independence, Missouri; Richard L. Ray of the National Atomic Museum, Albuquerque; and Spencer Wilson, Professor of History at the New Mexico Institute of Technology, who also doubles as the head of the Socorro Historical Society. I would also like to offer a special word of appreciation to Dana Asbury of the University of New Mexico Press and to Dorothy Wonsmos, head of the Interlibrary Loan Division, Zimmerman Library, University of New Mexico.

Personal interviews provide the most rewarding aspect of research in modern American history. I would like to thank the following people for taking time to share their recollections with me: Herbert L. Anderson, Hans A. Bethe, Berlyn Brixner, Ted Brown, Norris Bradbury, Holm Bursum, Jr., Roy W. Carlson, Sam P. Davalos, Neil Dilley, Frank DiLuzio, Hymer L. Friedell, Robert W. Henderson, Louis Hempelmann, Jr., Jack M. Hubbard, McAllister Hull, Jr., Leo M. Jercinovic, Kermit H. Larson, Dorothy McKibbin, John Magee, George Marchi, Lilli Marjon, James F. Nolan, Frank Oppenheimer, Lois Page, Thomas Treat, Stanislaw M. Ulam, Marvin and Ruby Wilkening.

Mel Merritt, Al Solomon, and Charles Wood always had valuable advice on whom to interview next. Louis Hempelmann, Jack M. Hubbard, Kermit Larson, John Magee, Noel Pugach, Jack Reed, Richard Robbins, Jr., and Donald Skabelund did yeoman work in giving a critical reading to various sections of the manuscript.

Kenneth T. Bainbridge critiqued an entire draft and provided valuable personal insights. I would also like to thank Kermit Larson for lending me his copies of the UCLA Trinity surveys, Mrs. Stafford Warren for allowing me to read her husbands reminiscences, Kenneth T. Bainbridge for letting me read his Columbia oral history, and Barton C. Hacker for lending me the draft version of his Elements of Controversy: A History of Radiation Safety in the Nuclear Weapons Testing Program. I would like to credit L. George Moses and George Lubick of Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, and Alfred Castle and William Gibbs of the New Mexico Military Institute in Roswell for permitting me to test out some of my early ideas on their unsuspecting students. Marion Honhart and, especially, Penelope Katson should be lauded for their efforts in deciphering my handwriting, some of which, I discovered, I couldnt read myself.

A special mention of thanks should go to Jack M. Hubbard, now retired in northern California. Hubbard graciously allowed me full access to his diary and his film record of the Trinity shot, and patiently answered all my questions about meteorology.

I also owe a word of appreciation to Eric, Chris, and Maria. They listened to a steady barrage of Los Alamos stories at dinner with only an occasional murmur of complaint. Chris even donated part of her Christmas vacation to help compile the bibliography. Finally, my thanks again to Margi, for her encouragement, her companionship, her mastery of the historical craft, and her sound editorial judgment. Her constancy in this regard is, as Shakespeare phrased it, a wondrous excellence.

THE

DAY

THE SUN

ROSE TWICE

Introduction

In December of 1945, the Indian pueblo of San Ildefonso, New Mexico prepared to celebrate its annual deer dance. That year they invited a square-dance club from nearby Los Alamos to join them, for the citizens of the famous Atomic City were soon preparing to leave the area. The Anglos from the Hill supplied several cases of Coca Cola while the Indians provided posole, green chile stew, and other native dishes. After the guests performed several square-dance routines, the Indians responded with one of their ancient dances. Finally, to the unusual accompaniment of accordion and Indian drums, the two groups danced together. In the midst of the festivities, the governor of the pueblo climbed on a bench and shouted above the din. This is the atomic age, he cried. This is the atomic age.

It was, indeed, the atomic age, and it had its beginnings on July 16, 1945, about 180 miles south of San Ildefonso in an area of the central New Mexico desert the Spanish termed Jornada del Muerto. The scientists called it Trinity Site, and this is how it appears on most modern maps.

The name Trinity is not well known by the general public. It evokes no image of recognition as do, say, Gettysburg, Pearl Harbor, or Harpers Ferry. A book entitled The Story of Trinity might well be misfiled in the religion section of many bookstores.

Yet New Mexicos Trinity falls into a far different category. As the site for the worlds first successful atomic detonation, it threw open doors that can never again be closed. What happened at Trinity that Monday morning must go down as one of the most significant events in the last thousand years.