Table of Contents

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press

London, England

Copyright 1992 by Robert Serber

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Scrber, R. (Robert)

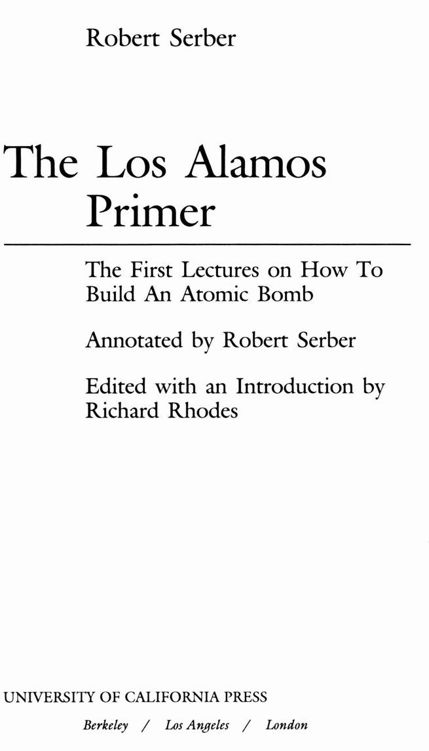

The Los Alamos primer : The first lectures on how to build an

atomic bomb / Robert Serber: annotated by Robert Serber;

edited by Richard Rhodes.

p. cm.

Based on a set of 5 lectures given by R. Serber during the first

two weeks of April 1943 as an indoctrination course in

connection with the starting of the Los Alamos Project.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-07576-4

1. Atomic bombUnited StatesHistory. 2. Manhattan

Project (U.S.)History. 3. Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory

History. 4. PhysicistsBiography. I. Rhodes, Richard. II. Title.

QC773.A1S47 1992

623.45119dc20 9114068

CIP

Printed in the United States of America

17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) ( Permanence of Paper ).

Richard Rhodes: Introduction

In late March 1943, in a dark time of world war, young scientists began arriving in Santa Fe, New Mexico, prepared to work on a new secret-weapons project just getting under way nearby. Officially they had been informed only that the projects successful culmination would probably end the war. Unofficially they understood that the work for which they were volunteering to live behind barbed wire for years to come, to return home only in cases of dire emergency, to delay finishing their doctoral studies or beginning their careers, was unprecedented and millennial; unofficially they whispered that they had signed on to attempt nothing less than inventing, designing, assembling, and testing the worlds first atomic bombsreleasing explosively for the first time the enormous energy confined within the nuclei of atoms. Other secret installations around the United States employing tens of thousands of workersat Oak Ridge, Tennessee; in Chicago at the University; on a barren site beside the Columbia River at Hanford, Washingtonwould painstakingly accumulate the few kilograms of exotic metals that the weapons would require; but the eager young team at Los Alamos would construct the actual weapons themselves.

Signing on to invent and craft new weapons of unprecedented destructiveness may seem bloodthirsty from todays long perspective of limited war and nuclear truce. Those were different times. War was general throughout the world, a pandemic of manmade death. Hundreds of thousands of other Americanssiblings and classmates and friendswere risking their lives on the front lines of North Africa and the Pacific islands. The death toll had already accumulated into the millions. There was reason to believe that the Germans might be at work on an atomic bomb, might even be ahead in the race, and the prospect of a Third Reich victorious with nuclear weapons chilled the soul. A new weapon in the American arsenal so destructive that it might frighten the belligerents into surrender seemed to many, in Winston Churchills postwar phrase, a miracle of deliverance.

The Army loaded the volunteers into olive-drab staff cars and jitneys and hauled them northwest of the New Mexico capital into the desert country beyond the Rio Grande. The vehicles negotiated a vertiginous unbarricaded road up the sheer wall of a canyon and came out onto a high, pine-forested plateau that jutted from the collapsed cone of the largest extinct volcano in the world. Los Alamos, the mesa was called, named for the cottonwoods that grew in the steep canyons that guarded its fastness. The construction site at the west end of the plateau, where a secret laboratory was being built, was a messheavy trucks and graders mucking through spring mudbut a core of handsome chinked-log buildings left over from the boys school that had formerly occupied the site offered sanctuary.

There was no time to waste. If the project on the Hill, as the place came to be called, would in fact end the war, then its challenges would be measured in human lives. While construction proceededwooden laboratories like stretched army barracks going up south of the school buildings across the main road, long vacuum tanks and massive electromagnets arriving shrouded on laboring flatbed trucksdiscussion at least could begin. It would continue, unceasing and obsessive, for two and a half years, to culminate in a vast, blinding fireball that turned a cold desert night into day.

The several dozen young Americansgraduate students and recent postdocswho came to Los Alamos found themselves working with distinguished men of science whom many of them knew only from their textbooks: J. Robert Oppenheimer, the secret laboratorys new director, a wealthy, cosmopolitan New Yorker who had come back from study in Europe in the late 1920s to found the first great American school of theoretical physics at the University of California at Berkeley; Enrico Fermi, the Italian Nobel laureate, one of the three or four greatest physicists of the century; I. I. Rabi, an American Nobel laureate, small and witty, who visited the Hill as a consultant but devoted his primary energies to working on radar at MIT; Edward Teller, a deep-voiced, excitable Hungarian theoretician of great versatility; Hans Bethe, an emigr from the anti-Semitic persecutions of Nazi Germany who had puzzled out the chain of nuclear reactions that fires the stars. Despite this leavening of older men (Oppenheimer was thirty-eight), the groups average age was only twenty-four.

An Oppenheimer protg, Robert Serber, a slim young Berkeley theoretician, quiet and shy but very much in command of his subject, began the work of the new secret laboratory with a series of lectures. Serber had guided a secret seminar at Berkeley the previous summer that invented and explored the ideas he was about to discuss; Oppenheimer, Bethe, and Teller were among the participants at the summer meetings in the conference room of Oppenheimers Berkeley office. Now at Los Alamos, with chalk in hand and a blackboard set up behind him, Serber proceeded to open the door to a new world.

The object of the project, the young theoretician began, scanning the expectant faces, is to produce a practical military weapon in the form of a bomb in which the energy is released by a fast neutron chain reaction in one or more of the materials known to show nuclear fission. That was news as well as confirmation, and his listeners let out their breaths. Those who had worked on the secret project elsewhere were amazed and delighted. Previously, to preserve military secrecy, they had only been allowed to know what immediately affected their work; now, as Oppenheimer had promised when he invited them to work at Los Alamos, they would know all. The barbed wire that would fence them in, the travel restrictions that would confine them there in the middle of the wilderness for the duration of the war, would also allow them scientific freedom of speech. Oppenheimer had convinced the army that open discussion, the lifeblood of science, was the only way to get the job done.

Bob Serber delivered five lectures in all. The raw new library rang with debate. Crew-cut Edward Condon, the associate director of the secret laboratory, kept notes. From day to day Condon and Serber worked up the notes into twenty-four mimeographed pages dense with formulas, graphs, and crude drawingsthe essence of what anyone in the world knew at that point about a secret new technology that would change forever the way nations thought about war. Puckishly, the two physicists titled the document the Los Alamos Primer. New recruits would be handed a copy as they arrived on the Hill (and arrive they did in the months to come, the Hill population doubling every nine months until it numbered more than five thousand by August 1945, the end of the war).