Groves, Leslie R., 1896-1970.

Now it can be told.

Copyright 1962 by Leslie R. Groves

Introduction copyright 1983 by Edward Teller

Published by Da Capo Press, Inc.

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

INTRODUCTION

Recently, several television dramas have examined the personalities and events of the atomic bomb project in Los Alamos, and interest in this watershed project has grown markedly. The recent seven-hour BBC production is perhaps the best of the offerings, but even there, historical inaccuracies and skewed perspectives are abundantly present. The readers of General Grovess own account are to be complimented for choosing to learn directly from one of the major participants. History in some ways resembles the relativity principle in science. What is observed depends on the observer. Only when the perspective of the observer is known can proper corrections be made.

General Groves was, perhaps above all else, a most straightforward man. He said what he thought with little consideration for the effect his opinions might have on others. Deviousness was totally foreign to his nature. Vannevar Bush, the head of all scientific wartime projects, interviewed General Groves prior to his appointment to the Los Alamos project. Bush suggested to the office of the Secretary of State that Groves might lack sufficient tact for such a sensitive role. It is typical of Groves that he has reported this opinion in his book.

The general was a direct man of practical action. His strengths included not only enormous dedication and a great capacity for work, but also an unconcerned approach to complicated problems. He very often managed to ignore complexity and arrive at a result which, if not ideal, at least worked. Groves was also incredibly versatile, a quality required for such an unprecedented job as organizing the enterprise that led to the first atomic bomb. He had to worry both about the diffusion of uranium hexafluoride molecules and about the problems faced by the wives in Los Alamos. (As Groves mentions, contrary to local gossip, Los Alamos was not an establishment for the care of pregnant WACs). He organized the intelligence effort to determine the Nazi prospects of building an atomic weapon of their own, and he influenced, perhaps not in the right way, the decision to drop the bomb on Hiroshima.

For Groves, the Manhattan Project seemed a minor assignment, less significant than the construction of the Pentagon. He was deeply disappointed at being given the job of supervising the development of an atomic weapon since it deprived him of combat duty. He started with, and partially retained, thorough doubts about the feasibility of the project. Yet in convincing the leaders at DuPont that they should participate, he appeared totally confident in order to overcome the incredulity of those overly sane chemical engineers. I would ascribe his behavior in this case less to a lack of openness than to his unwavering sense of duty as an Army officer.

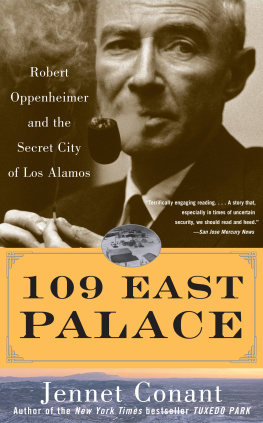

Groves, as history records, was eminently successful as the military director of the Los Alamos Lab. Perhaps his most outstanding decision was the choice of J. Robert Oppenheimer to administer the scientific work at the laboratory. In the fantastic story of the atomic bomb, this less obvious, less remembered but no less vital story of the highly effective cooperation between two individuals, poles apart in every way, remains unique.

Oppie clearly saw the importance of the project and envisioned the new age that would arise from the old. While Oppie resembled General Groves in the intensity of his effort and dedication, his gentle demeanor, social grace even his physique showed a marked contrast to the Generals. But the greatest difference between the two men lay in the complexity of their personalities. Oppenheimer was so extraordinarily complicated and clever that he could mask these qualities with an appearance of simplicity. Grovess astuteness is most clearly demonstrated in that, despite opposition from the military security division whose value and function he supported and even overestimated, he selected Oppenheimer as scientific director. The contrast and cooperation of Groves and Oppenheimer is the most striking human story in the Manhattan Project.

Much of my life has been spent in laboratories of similar size and complexity to the Los Alamos Laboratory. I have known many directors intimately. For a short time, I was even a director myself. I know of no one whose work begins to compare in excellence with that of Oppenheimers.

Oppie knew in detail the research going on in every part of the laboratory, and was as excellent at analyzing human problems as the countless technical ones. Of the more than 10,000 people who eventually came to work at Los Alamos, Oppie knew several hundred intimately, by which I mean that he understood their relationships with one another, and what made them tick. He knew how to lead without seeming to do so. His charismatic dedication had a profound effect on the successful and rapid completion of the atomic bomb.

Some of Oppenheimers qualities come through in the recent BBC production. However, General Groves, in this television drama, is rather inadequately presented. (Even his girth was underestimated.) Obviously no one with so little intelligence, as the General Groves presented by the BBC, could have met the massive responsibilities of providing shelter, equipment, and materials with so little delay and impediment to the project. I must confess, however, that between 1943 and 1945 General Groves could have won almost any popularity contest in which the scientific community at Los Alamos voted.

I remember a meeting early in 1943 at which Oppie announced a revision in security clearance procedures, made necessary by the fact that so many of us could not be cleared under the usual regulations. The new rules called for us to clear one another by vouching for our good intentions and backgrounds. Someone piped up, Does that mean that clearance will be based on our scientific good names? Oppie responded, Grove doesnt believe we have any other. We laughed. General Groves, or His Nibs as we called him, could hardly have been completely unaware of Oppies and our attitudes. He chose to disregard them.

No one should be surprised that a group of independent scientists found General Groves and his regulations irritating. Secrecy runs contrary to the deepest inclinations of every scientist; we were willing to make sacrifices, even when they seemed ludicrous, because of the war. But military regulations affected every detail of our lives and, worse, they were worded as if we lacked the common sense of a five-year old. I recall a directive issued in early 1945 during the only serious water shortage at Los Alamos. The order did not carry General Grovess signature, but we all attributed it to him. It detailed the ways in which the shortage would be met and concluded with the memorable sentence: Residents will not use showers except in case of emergency.