IMAGES

of America

THE MANHATTAN PROJECT

AT HANFORD SITE

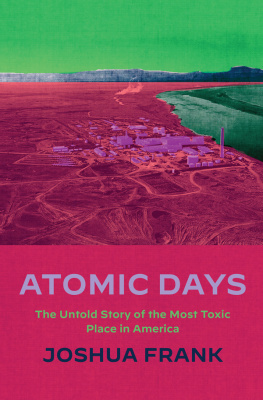

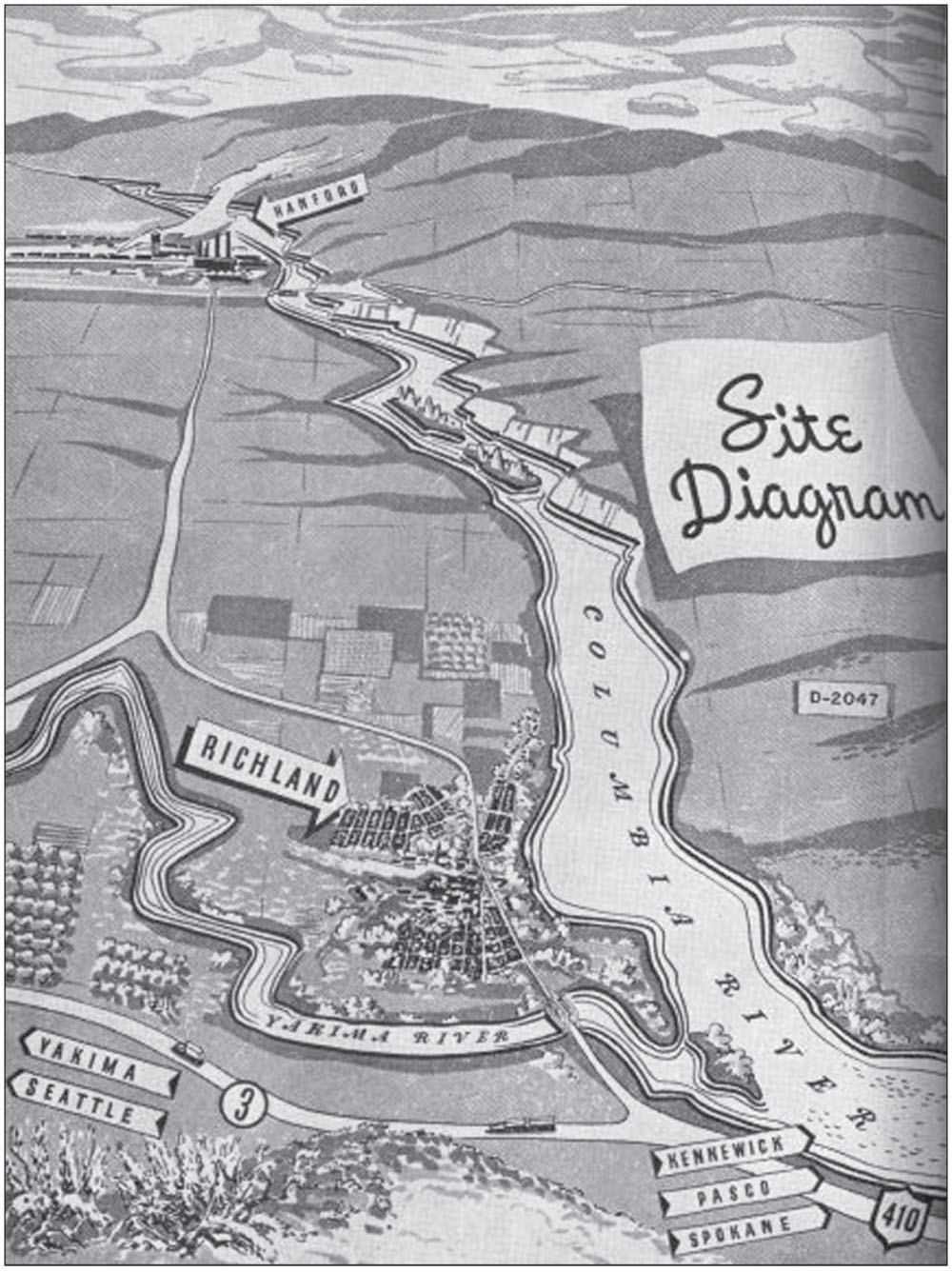

The Hanford Site, selected as part of the supersecret World War II Manhattan Project, was 670 square miles of isolated land in the desert of southeastern Washington. (Courtesy of US Department of Energy Declassified Document Retrieval System.)

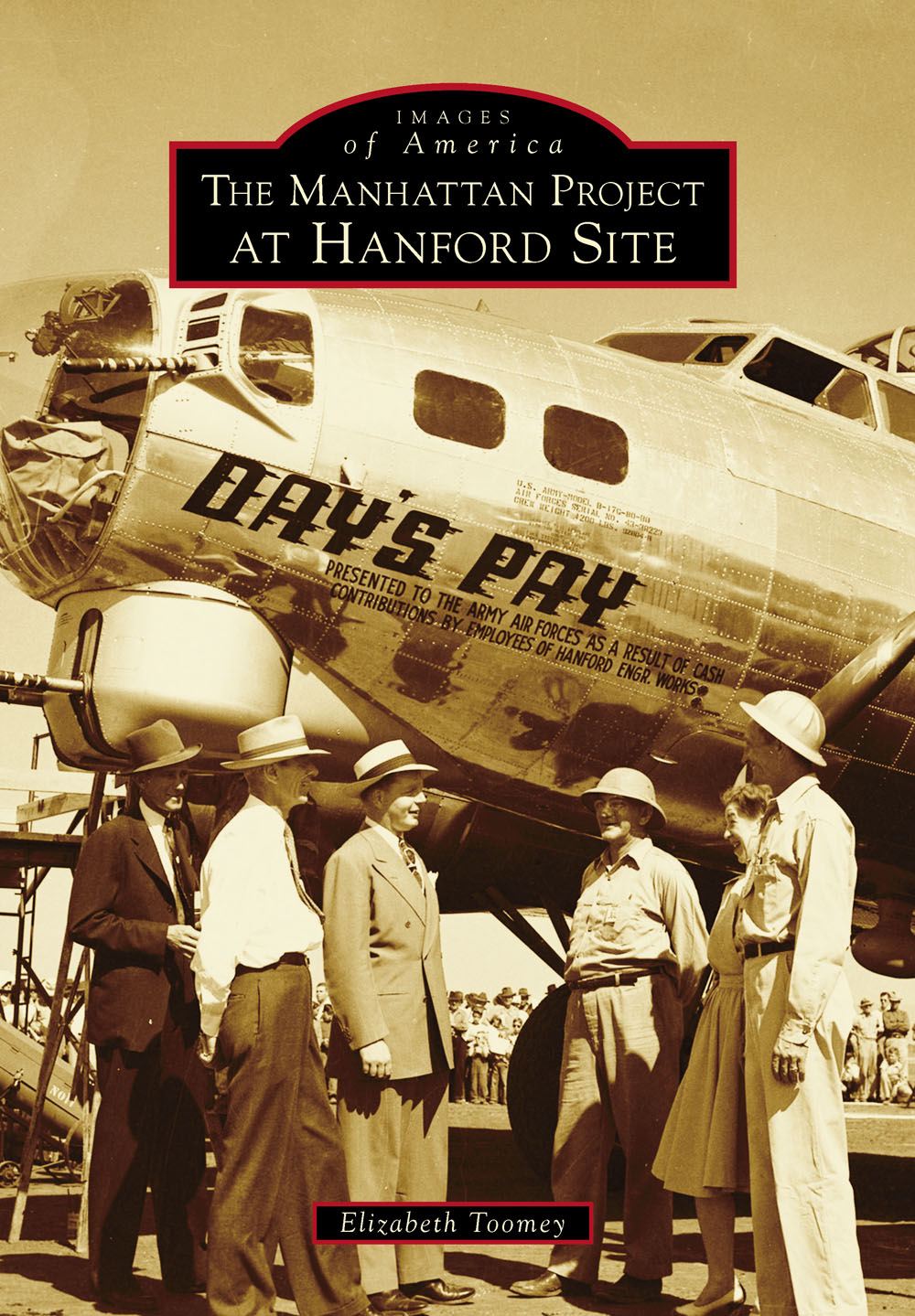

ON THE COVER: The B-17G Days Pay is pictured at the Hanford Airport on July 23, 1944. (Courtesy of US Department of Energy Declassified Document Retrieval System.)

IMAGES

of America

THE MANHATTAN PROJECT

AT HANFORD SITE

Elizabeth Toomey

Copyright 2015 by Elizabeth Toomey

ISBN 978-1-4671-3444-6

Ebook ISBN 9781439654255

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015939362

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To my mother, Diana, who brought World War II and the occupation to life through her stories as a Japanese linguist for the US Army Intelligence

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

An early love of World War II history that was fostered by my parents, Paul and Diana, who served as Japanese linguists in the US Army Intelligence during the war and the Occupation of Japan, and a career that led to managing the REACH museum project, resulted in the writing of this book. The REACH opened on July 4, 2014, dedicated to sharing our communitys stories. One of those stories was our historic role in the secret Manhattan Project. Site W, as Hanford was known, developed plutonium for the Fat Man bomb, which led to Japans surrender. It was a turning point in world history and one of the most incredible stories of all time. Hanford was critical to the war effort, encompassing massive construction, patriotism, secrecy, urgency, research, and innovation that began the Atomic Age. The narrative herein is based on publicly available historic research conducted by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, HistoryLink.org, Port of Pasco, University of Washington, Boeing, ALCOA, US Department of Energy (and its predecessor agencies), Bureau of Reclamation, Bonneville Power Administration, Mick Qualls, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, Franklin County Historical Society, Kadlec Hospital, Wanapum Band, Atomic Heritage Foundation, and other open source materials available on the web.

This publication is intended to serve as a companion piece to the REACHs exhibit on the Manhattan Project-Hanford Engineer Works. Special thanks to my husband, Jim, and kids Chris, Megan, and Shannon for supporting my weekend job writing this book; Dan Ostergaard for assistance with photograph identification; Nancy Bowers, REACH volunteer, for extraordinary editing and selection of photographs; Dianna Millsap at the REACH for project management and coordination, selection of photographs, and moral support; not to mention the rest of the REACH staff who put up with one more project to help in our storytelling efforts. Catherine Johnson-Pearsall (CJP) allowed access to her private collection of photographs taken by Robley Johnson, the official Hanford photographer during the Manhattan Project and beyond.

Unless otherwise noted, the photographs used in this publication are from the public domain, which to the best of my knowledge either have no registered copyright or the copyright has expired. Quotes from Robley Johnson are from an interview by Ted Van Arsdol, entitled Robley Johnson Remembers, 1991. We believe this story will fascinate and inspire you as much as it has inspired us.

INTRODUCTION

There are very few moments in US history that have captured the hearts and minds of American citizens more than World War II. Studying the Good War reveals to those who came later that it was at once both frightening and exciting. There was an important role for everyone to play, whether it was to serve in the military, work in a factory, grow a victory garden, volunteer at a USO hall, buy a war bond, or even embrace rationing. Americans exemplified patriotism in every aspect of their lives. And for some, it meant working on the most secret project in American history.

Early in 1939, the worlds scientific community discovered that German physicists had learned the secrets of splitting a uranium atom. Fears soon spread over the possibility of Nazi scientists utilizing that energy to produce a bomb capable of unspeakable destruction. Scientists Albert Einstein, who fled Nazi persecution, and Enrico Fermi, a physicist who left Fascist Italy for America, encouraged the United States to begin atomic research. They agreed that the president must be informed of the dangers of atomic technology in the hands of the Axis powers. Fermi traveled to Washington, DC, in March to express his concerns to government officials. Le Szilrd, who had left Hungary, wrote a letter to President Roosevelt that was signed by Albert Einstein urging the development of an atomic research program later that year. Roosevelt saw neither the necessity nor the utility for such a project but agreed to proceed slowly.

In late 1941, the American effort to design and build an atomic bomb received its code name, the Manhattan Project. Secrecy was paramount. Neither the Germans nor the Japanese could learn of the project. President Roosevelt and Winston Churchill also agreed that Joseph Stalin would be kept in the dark. Consequently, there was no public awareness or debate. Only a small privileged cadre of inner scientists and officials knew about the atomic bombs development.

The Manhattan Project operated like a large construction company. It purchased and prepared sites, let contracts, hired personnel and subcontractors, built and maintained housing and service facilities, placed orders for materials, developed administrative and accounting procedures, and established communications networks. By the end of the war, $2.2 billion ($26 billion in todays dollars) had been spent. What made the Manhattan Project unlike other companies performing similar functions was that, because of the necessity of moving quickly, it invested hundreds of millions of dollars in unproven and hitherto unknown processes and did so entirely in secret.

The Manhattan Project might have been a massive construction project, but it was a military operation from the get-go. It was funded by president and commander in chief Franklin D. Roosevelt, led by Secretary of War Henry Stimson, and administered by Gen. Leslie R. Groves of the US Army Corps of Engineers. It took scientist J. Robert Oppenheimers galaxy of luminaries to solve the science of atomic bombs; it took Americas leading industrial powerhouses to engineer the solutions; it took career bureaucrats at all levels of government to remove the obstacles and smooth the path forward. But it took a uniquely military perspective on what General Groves called the exigencies of warthe understanding that a Fascist world was a very real possibility and that the development of overwhelming, coercive power was the only way to guarantee quick and decisive victory to get the job done. The Manhattan Project took the United States from theoretical physics all the way to a working atomic bomb in under three years time.

Next page