Published by Echo Point Books & Media

Brattleboro, Vermont

www.EchoPointBooks.com

All rights reserved.

Neither this work nor any portions thereof may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any capacity without written permission from the publisher.

Copyright 1971, 2020 Terence McLaughlin

Dirt

ISBN: 978-1-62654-945-4 (casebound)

978-1-62654-946-1 (paperback)

978-1-64837-102-8 (eBook)

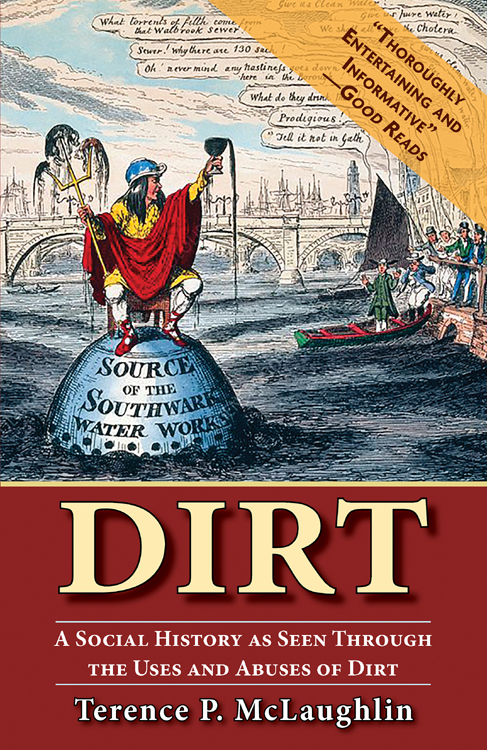

Cover design by Kaitlyn Whitaker

Cover image: Londons water supply, 1828 caricature by George Cruikshank; courtesy of Science Photo Library Historical artwork by the British caricaturist George Cruikshank (1792-1878), showing people protesting against sewage polluting Londons water supply. At centre, John Edwards, the owner of the Southwark Water Works is sitting on a toilet with a chamberpot on his head, on a globe in the Thames, raising a goblet of polluted water to the crowds on the river bank. Dead animals are on the trident in his hand. Sewers bring excrement into the river, and washer women (left) attempt to clean clothes. In the background is London Bridge and the sailing ships and buildings of early 19th century London. Unlike the owners of other water companies, Edwards had failed to improve the sourcing and quality of the drinking water he supplied, despite an 1828 report calling for reforms.

To Eve

Who first made history interesting

1. Introduction

Dirt is evidence of the imperfections of life, a constant reminder of change and decay. It is the dark side of all human activitieshuman, because it is only in our judgements that things are dirty: there is no such material as absolute dirt. Earth, in the garden, is a valuable support and nourishment for plants, and gardeners often run it through their fingers lovingly; earth on the carpet is dirt. A pile of dung, to the dung-beetle, is food and shelter for a large family; a pile of dung, to the Public Health Inspector, is a Nuisance. Soup in a plate, before we eat it, is food; the traces that we leave on the plate imperceptibly become dirt. Lipstick on a girls lips may make her boy-friend more anxious to touch them with his own lips; lipstick on a cup will probably make him refuse to touch it.

Because of this relativity, because dirt can be almost anything that we choose to call dirt, it has often been defined as matter out of place. This fits the earth (garden)/earth (carpet) difference quite well, but it is not really very useful as a definition. A sock on the grand piano or a book in a pile of plates may be untidy, and they are certainly out of place, but they are not necessarily dirty. To be dirt, the material also has to be hard to remove and unpleasant. If you sit on the beach, particularly if you bathe, sand will stick to you, but not many people would classify this as dirt, mainly because it brushes off so easily. However, if, as often happens, the sand is covered with oil, tar, or sewage, and this sticks to you, it is definitely dirt.

Sartre, in his major philosophical work on Existentialism, Ltre et le Nant, presents a long discussion on the nature of sliminess or stickiness which has quite a lot to do with our ideas of dirt. He points out that quite small children, who presumably have not yet learned any notions of cleanliness, and cannot yet be worried by germs, still tend to recognize that slimy things are unpleasant. It is because slimy things are clinging that we dislike themthey hold on to us even when we should like to let them go, and, like an unpleasant travelling companion or an obscene telephone caller, seem to be trying to involve us in themselves.

If an object which I hold in my hands is solid, says Sartre, I can let go when I please. Yet here is the slimy reversing the terms I open my hands, I want to let go of the slimy material and it sticks to me, it draws me, it sucks at me. Its mode of being is neither the reassuring inertia of the solid nor a dynamism like that in water which is exhausted in fleeing from me. It is a soft yielding action, a moist and feminine sucking, it lives obscurely under my fingers.

This is the feeling of pollution, the kind of experience where something dirty has attached itself to us and we cannot get rid of the traces, however hard we try. Ritual defilement is one aspect of this feeling, and one which provides an enormous field of study for anthropologists (when they are not engaged in their favourite activity of reviling one another), but powerful irrational feelings of defilement exist in the most sophisticated societies. Try serving soup in a chamber-pot. However clean it may be, and however much a certain type of guest may find it amusing, there will be a very real uneasiness about the juxtaposition. There are some kinds of dirt that we treat, in practice, as irremovableas in the case of the old lady who was unlucky enough to drop her false teeth down the lavatory, where they were flushed into the sewer. When a search failed to find them, she heaved a sigh of relief. I would never have fancied them again, she said, and most people would agree. Even things which in themselves are clean, but can be associated with dirt, tend to be suspect. Vance Packard, in The Hidden Persuaders, quotes the sad story of a company who tried to boost their sales of soup mix by offering free nylon stockings. The scheme was a complete fiasco. people seeing the offer were offended. Subconsciously they associated feet and soup and were alienated because they didnt like the idea of feet being in their soup. Faced by such reactions from industrialized society, we are in a better position to understand such primitive taboos as the fact that, for instance, a women of the Lele tribe who is menstruating must not cook for her husband or even poke the fire that is used for cooking.

Sartre, in his analysis, goes on to discuss the fear and disgust inspired by slimy things. When we touch them, they not only cling to us, but the boundary line between ourselves and the slime is blurredif we dip our fingers in oil or honey (Sartres favourite exemplarit is difficult to tell whether he likes honey or dislikes it so intensely as to have a fixation about it) it hangs in strings from our fingers, our hands seem to be dissolving in it:

To touch slime is to risk being dissolved in sliminess. Now this dissolution by itself is frightening enough but it is still more frightening in that the metamorphosis is not just into a thing (bad as that would be) but into slime.

There is a feeling of helplessness when you are faced by something slimy: the real horror to some of eating oysters is that, once the thing is in your mouth, there is no way of avoiding eating all of it. Other food of a strange character may be sampled in nibbles or sips, and if it is too distasteful you can stop; oysters take over the situation as the dominant partner. The same applies to the raw herrings beloved by the Dutch.