The Queens Hand

THE MIDDLE AGES SERIES

Ruth Mazo Karras, Series Editor

Edward Peters, Founding Editor

A complete list of books in the series

is available from the publisher.

The Queens Hand

_________________

Power and Authority in the Reign

of Berenguela of Castile

Janna Bianchini

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANI A PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2012 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bianchini, Janna.

The Queens hand : power and authority in the reign of Berenguela of Castile / Janna Bianchini. 1st ed.

p. cm. (The Middle Ages series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4433-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Berengaria, Queen of Castile and Leon, 1181?

1246. 2. QueensSpainCastileBiography.

3. Castile (Spain)HistoryHenry I, 12141217.

4. Castile (Spain)HistoryFerdinand III,

12171252. 5. SpainKings and rulersBiography.

6. WomenHistoryMiddle Ages, 5001500.

I. Title. II. Series: Middle Ages series.

DP139.5.B53 2012

946'.302092dc23 2012007856

[B]

For Natka: each day with you is a blessing.

Contents

A Note on Names

Medieval historians always have to wrestle with the problem of rendering medieval names into modern prose. My method has been to name people and places according to the language presently spoken in their region: French in modern France, Spanish in modern Spain, and so on. Of course, even this has its challenges. Popes and emperors appear in their standard Anglicized forms. The names of places across present-day Spain appear in Castilian; so do the names of Castilian and Leonese people. The names of people from Aragn-Catalua are given in Catalan, partly to reflect the language many of them spoke, and partly to help readers distinguish among the seemingly infinite number of royal Alfonsos who populate twelfth- and thirteenth-century Iberia. In Castilian the name is Alfonso; in Catalan, Alfons; and in Portuguese, Afonso.

Standardizing medieval names according to modern norms inevitably costs some authenticity, however. For example, the men I identify here as Rodrigo or Rodrguez often spoke of themselves as Ruy or Ruiztheir names are written that way in some medieval charters. More often, though, scribes recorded them as Rodericus or Roderici, and I use the more Latinate form of the name for that reason. Similarly, I have used the Anglicized version of a few European place names, most notably Castile and Navarre, for the sake of readability in English.

The names of royal women reflect the language of the kingdom into which they married, rather than the one in which they were born. A queen usually spent most of her life in her husbands homeland, and became part of its history. So we have Blanche of Castile, rather than Blanca, and Leonor of England, rather than Eleanor.

Finally, readers should note that in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Castilian and Leonese noble families had not yet acquired stable patronyms. The great families were beginning to be identified with specific locations Haro, Lara, Castro, and so onand I use these names far more extensively than the magnates themselves did. Noble children identified themselves primarily by their fathers name, which means patronyms changed from generation to generation. Thus Diego Lpez was the son of a man named Lopeadding ez to a name signified child of. This can become confusing, because Castilian and Leonese families tended to recycle names. Diego Lpez might name his oldest son after his father, Lope, so that the son would be known as Lope Daz. Lope Daz might name his oldest son after his father, creating another Diego Lpezand so on.

In all these cases, I have done my best to marry readability and authenticity. If the marriage sometimes flounders, the responsibility is mine.

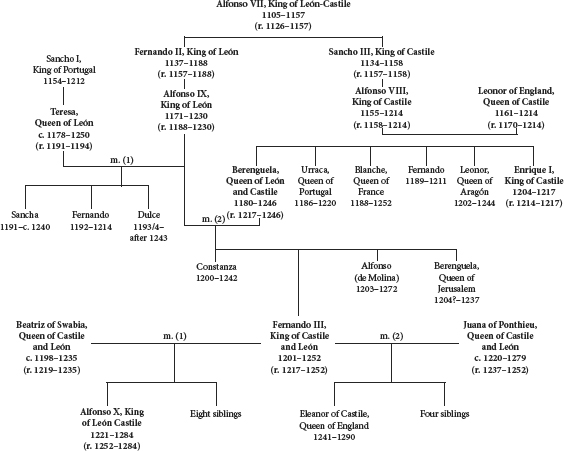

Figure 1. The royal houses of Len and Castile.

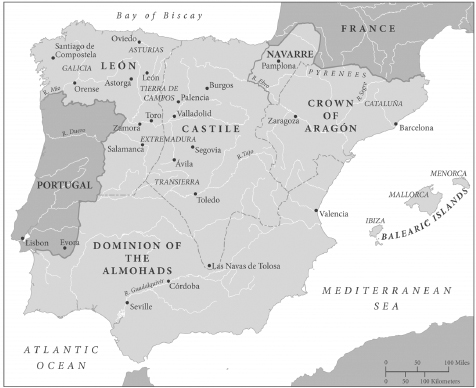

Figure 2. Iberia in the early thirteenth century.

Introduction

Berenguela of Castile is not a household name. Even in her native Spain, and even among historians, mention of her is often greeted with a puzzled smile. Compared to her grandmother Eleanor of Aquitaine or her sister Blanche of Castile, she is at best an obscure figure in the already shadowy ranks of medieval queens.

During her lifetime, though, Berenguela was one of the most powerful women in Europe. Contemporary sources, both narrative and documentary, praise her accomplishments and authority in terms rarely accorded to women. They leave no doubt that Berenguela was responsible for major events in thirteenth-century Spanish history, from the conquest of Muslim Crdoba to the unification of the kingdoms of Castile and Len.

Her fall from such prominence to such obscurity is not altogether mystifying. Like most medieval women, she was a casualty of gender bias in the work of medieval, early modern, and modern historians. To some extent, she was also affected by what was, until quite recently, a disdain for Iberian history on the part of European and North American scholarsalthough those attitudes cannot explain her near-total absence from Spanish historiography as well. In the Spanish context, the most important obstacle to a full recognition of her significance was that she had a sonand not just any son. She was the mother of Fernando III, San Fernando, the crusading saint-king whose spectacular successes in the Reconquista could have made him a legend all by themselves. Combined with his canonization as a Catholic saint, they instead made him a figure of such cultural stature that it can be difficult to tease the historical fact of his life away from its mythos. That mythos does not easily accommodate anyone elses contributions to its heros legacy certainly not his mothers.

It is not my purpose to degrade Fernando IIIs achievements. I want only to consider the early thirteenth century from a different angle, one that centers on Berenguela rather than her son. It is not possible to understand the history of Castile and Len as long as the history of women is excised from it. But to say that Berenguelas pivotal role during her sons reign subtracts anything from Fernando IIIs own significance creates a false dichotomy. History is not a zero-sum game. In Berenguelas case and that of many other women, however, it has been treated as one; Fernando IIIs success has been allowed to eclipse his mothers. And her career deserves to be studied in its own right.