Preface

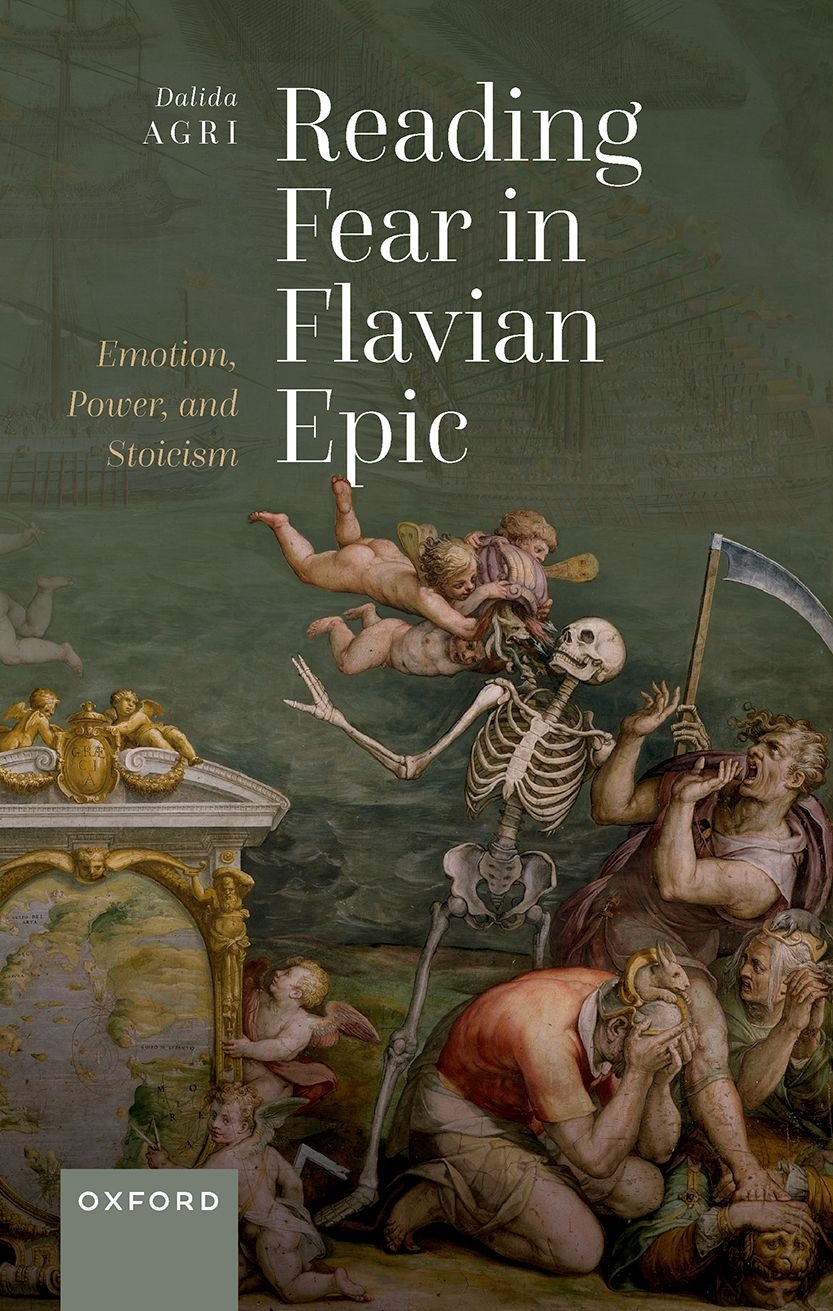

The purpose of this book, its structure and arguments are all laid out in the Introduction. Here I wish to say a few words about the book and acknowledge the people who have contributed to it through their time and support. This is a project that has long been brewing, and which has taken several forms before settling into the one fleshed out in this volume. A few years ago, this book started as a chapter on fear within a greater project on emotions in Flavian epic. Very quickly, fear took over and it became clear that this is a topic demanding its own space. There is still much to do on the subject of emotion and the adopted angle is one among many. A lot of the ancient material that I have come across still resonates with domestic and global political events incurred in recent times, reminding me how lucky we are to be still able to study these texts and read the world around us in a way that helps keep the fear at bay.

I feel immense gratitude to everyone who helped along the way, read parts of the manuscript and offered feedback. First, I wish to thank Roy Gibson, for his incredible support and words of wisdom, a source of strength over the years; Ruth Morello, my friend and partner-in-crime at Manchester, not only for sharing books and insights into the elusive art of academic writing, but also for reading an early draft, and, as always, suggesting clever ways to improve it. My warmest thanks go to Susanna Braund for her thoughtful feedback on and encouragements. I am extremely grateful to Charlotte Loveridge at OUP, for her care and diligence in relation to the submission and consideration of the manuscript, and to her team throughout the process that led this book to see the light. I am exceedingly indebted to OUPs two anonymous readers who contributed so much to improve the book throughout the review process, providing excellent suggestions, support, and commitment to see this book through all the way to publication. Theodore Antoniadis, one of the two anonymous readers, and who waved his anonymity, deserves special mention for extending his help beyond the call of duty, even offering last-minute advice. Very special thanks to Chris Leckey and Amy Mockridge, my former brilliant discipuli at Manchester, for reading and commenting upon early drafts, and for their intellectual enthusiasm, which was most heartening and stimulating, as we would find ourselves digressing on the ancient world, tyrants, Stoicism, and psychoanalysis at ungodly hours. Chris also proved tremendously helpful with last-minute editing. Finally, I am most grateful to my husband, Arman Kevric, for so elegantly stepping into the role of my very own Maecenas, for being a constant source of intellectual challenge and stimulation, for reading very early drafts and pushing me to think harder about the nature of ideas, effective communication, and for whom we really write.

Contents

For most classical texts, I have used the Loeb edition, except for Senecas De Clementia, for which the 2009 edition by S.M. Braund is preferred (see item as listed in the Bibliography). Translations are my own, unless otherwise stated. Abbreviations for ancient authors and their works generally follow the list in Hornblower, Spawforth, and Eidinow (eds), the Oxford Classical Dictionary (4th edition, Oxford). The following abbreviations are used for works that are the subject of an individual chapter in this book and for frequently cited texts:

Virgil, Aeneid

Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica

Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica

Lucan, Bellum Civile

Homer, Iliad

Ovid, Metamorphoses

Silius Italicus, Punica

Seneca, Epistulae Morales

Statius, Thebaid

For journals and periodicals, I have mostly used the abbreviations in LAnne Philologique. Note also:

Aufstieg und Niedergang der rmischen Welt (Festschrift J. Vogt), ed. Temporini H. and Haase W. (1927). Berlin and New York: de Gruyter

The Cambridge Historical Journal

American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition: Washington DC, 1980 = DSM-III

Forcellini E., Totius latinitatis lexicon (Padua 18641913)

Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics

Lewis C.T. and Short C., A Latin Dictionary (1879)

Oxford Latin Dictionary, ed. Glare P.G.W. (Oxford, 196882)

Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta, ed. J. von Arnim (Leipzig, 1905, repr. Stuttgart 1964)

Thesaurus Linguae Latinae (Leipzig, 1900)

The ubiquitous figure of the tyrant in the Flavian epics reveals a sustained poetic interest in the tyrants psychology and their relationship to power. Fear, surprisingly, is the one crucial emotion that has received the least attention, despite its importance in ancient constructions of tyranny, and the obsession with fear in Flavian epic discourse on tyrants and their passions.

In the Rome of the early Empire (first century ad ), such an obsession neatly squares with the dependence on fear as a governing principle, the shift of imperial power into monarchy, often akin to the rule of tyranny, a stream of emotionally unstable emperors, the end of a dynasty and the advent of a new one. Of course, the civil wars of ad 69, the notorious Year of the Four Emperors, re-opened a wound in the Roman psyche. In Flavian epic, the recurring image of the rulers lack of grip over his passions inevitably leads to violence, civil strife, and political turmoil. This is already foreshadowed in a number of Senecas plays,