First published 2002 by Pearson Education Limited

Published 2014 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2002, Taylor & Francis.

The right of Johanna Alberti to be identified as Author

of this Work has been asserted by her in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

ISBN 13: 978-0-582-40463-2 (pbk)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the British Library

Typeset in 11/13pt Baskerville MT by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong

The author would like to acknowledge Clive Emsley as the initiator of this volume. He also read it through in draft and offered encouraging and constructive comments which were immensely valuable. She is delighted to acknowledge extensive assistance from Sam Alberti in checking all things checkable on the world wide web. Irene Dunn at the Robinson Library, University of Newcastle, has been, as always, unfailingly helpful.

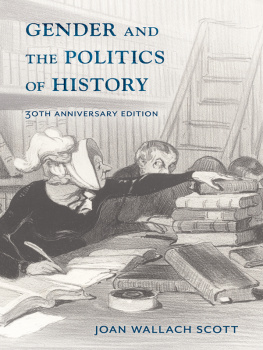

This book examines the writing of historians of women from 1969 to 1999. The title of the book reflects a change in the angle from which the history of women has been viewed during this period. Gender, Jane Flax has declared, is a category that feminist theorists have constructed to analyze certain relations in our cultures and experiences. The concept must therefore reflect our questions, desires, and needs.1 The questions, desires and needs which led to the widespread use of the word gender in studies by historians of women are varied and complex. Joan Scott suggested that one motivation was the desire to gain academic legitimacy because the term womens history contained a threat to the widely accepted view that women were not Valid historical subjects, and was associated with the assumed stridency of feminism.2 Her own use of the term was fuelled by a determination to transform the discipline of history. Later chapters will explore in more detail the emergence of gender history from womens history.

In this introduction I want to provide some sense of the writing that has preceded the work of historians of women during the past thirty years. The context, in which the wave of writing which this book covers took place, was one in which men dominated writing of history and defined what historians should and could do. The customs of history writing and the justification for the historians craft, which were current when the work covered by this book began, will be given a necessarily cursory summary. Alongside this narrative will be placed a selection of the ways early historians of women have been presented to the modern reader by the current generation of historians of women. There is included within this selection a more detailed description of the writings of three women historians of women who wrote in the first half of the twentieth century: Alice Clark, Ivy Pinchbeck and Mary Beard. My purpose is to place some of the ideas put forward by recent historians of women within a broader context.

The form in which history writing has appeared differs from one period to another. History as we practise it today has its roots in the nineteenth century: historians of the generation who were teaching in the sixties the early period of the expansion of university education in the Western world based their practice firmly on nineteenth-century traditions. In particular, the historian Leopold von Ranke has cast a long shadow over the work of historians since the second half of that century. Ranke worked at a time when historians were faced with a deluge of information.3 His most innovative conception for the practice of history was his insistence that historians should use contemporary documents. Reacting against the writing of history which drew moral lessons about the past, he asserted that the task of the historian was to view the past in a detached manner. If this task was rigorously pursued then he believed that it was possible to narrate the events of the past wie es eigentlich gewesen (as they actually happened.) The historian, in this perspective, is simply a mirror for the events of the past, albeit one that selects what it reflects. This approach to history is one that has persisted.

Rankes assertion of the ability of historians to reinscribe the past on to the pages of the present co-existed with another way of seeing the work of a historian which has had less of a powerful influence in the last one hundred years, but has never been totally superseded. However, history as a creation of the historian, a story or a tale, literary history, has deep roots in the earliest known human cultures. In this tradition the quality of the telling is vitally important, although no tale is told without a purpose. Usually histories were used by those with religious or secular power to justify their positions. But groups of people without much power could also use the telling of history for their own purposes. This is a tradition to which the writing of the history of women has strong links. Bonnie Smith has written that Without a historian any group remains oppressed, living in silence, bonds, and suffering, until that moment when, as in Whig history, a historical narrative reveals its struggle for liberation. Smith sees the history of women as sharing many traits with Whig history of the past or working-class and black history today, the history of women maintains its affinity, however, weakened, with an epic or romantic tradition.4

Bonnie Smith and other historians of women have been concerned to trace the roots of their practice in an earlier age. Smiths goal in doing this was to link women scholars to the historiography of women by tracing a kind of genealogy of womens historiography parallel to that of better-known men. She has provided a thorough and assertive examination of the contributions of womens historians to history writing. Nathalie Zemon Davis traced the history of women in history back to Plutarchs little biographies of virtuous women, a