First published 1977 in Great Britain by Frank Cass and co.ltd

Published 2019 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1977 by Tony Barnett

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

c/o Biblio Distribution Center

Typeset by Preface Ltd., Salisbury, Wilts.

ISBN 13: 978-0-7146-3060-1 (hbk)

Acknowledgements

The financial support for this research was provided by a generous grant from the Social Science Research Council during 1970 and 1971. A smaller grant from the Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies of the University of Durham enabled me to make a brief return visit to the Gezira in 1972.

I am indebted to many individuals for help with this book, not least to the people of Nueila village and the officials of the Sudan Gezira Board. A number of people helped me to clarify my ideas on parts of the book, notably Talal Asad, Herbert Farbrother, Gavin Williams and Shahida A1 Baz. The maps and diagrams were drawn by Barbara Satchell.

My greatest debt is to my wife, Marilyn, who worked with me in the field, and collected much of the data upon which this book is based.

Nueila is a real village, but I have changed the names of many of the people in order to preserve a degree of anonymity.

With regard to the transliteration of Arabic words, I have not followed any standard system. I have, however, tried to be consistent.

Needless to say, any errors of fact, analysis or interpretation are my own.

T. Barnett

Norwich

1977

Chapter 1

Background to the Gezira Scheme

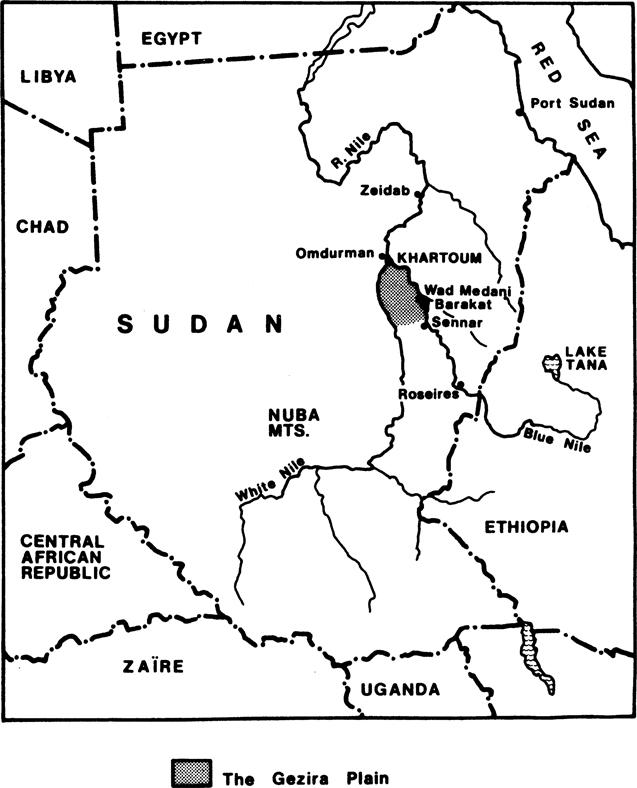

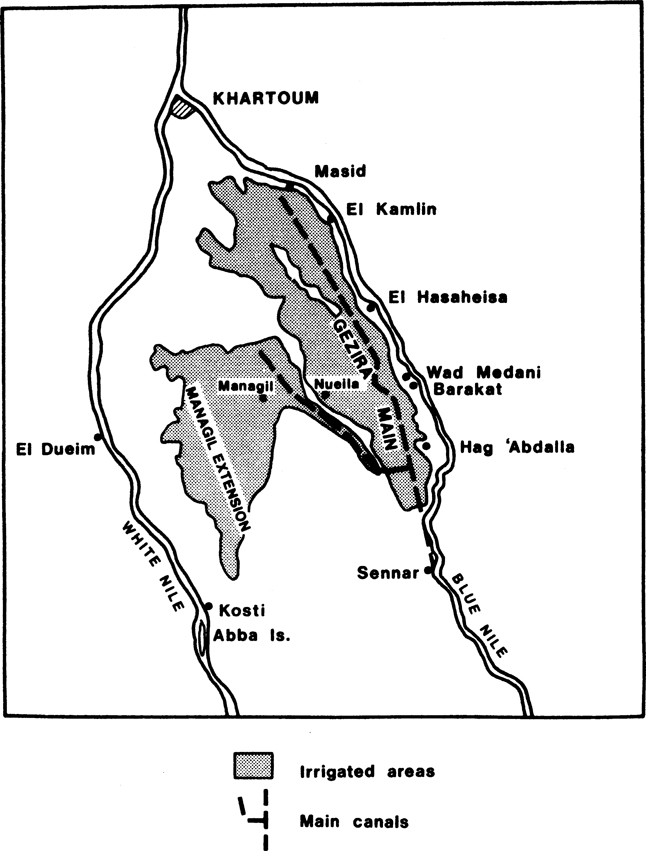

Gezira is the Arabic word meaning island or peninsula. It crops up in place names throughout the Arab world, notably in the name Algeria which is an anglicized form of the Arabic al-guzayir , the islands. In the Sudan, Gezira means only one thing. It refers to that vast area of land which lies between the Blue and the White Nile. In particular, though, it refers to the part of that area which is irrigated and used for growing cotton, the staple export crop of the country.

Some Geographical and Climatic Considerations

The central area of the Sudan is characterized by huge expanses of clay plains. They stretch from the Nuba Mountains to the Ethiopian border ( considers that this general area of the clay plains must be divided into a northern and a southern region, such is the diversity between the desert north and the scrub and tropical forest of the south. This division is understandable; for from the north to the south of the clay plain area is a distance of about 1400 kilometres. The clay soils are of considerable importance to the present structure of the Sudans economy. And within the region, the Gezira Scheme is of overwhelming importance.

The most outstanding feature of the Gezira area is its crushing monotony. Two impressionistic accounts will say more than any technical details. Barbour wrote:

to the South of Khartoum one can stand in an apparently absolutely flat plain of grey cracked clay, where the thin natural vegetation has all been cleared and where there is neither a hill nor a village nor a tree nor a blade of grass in sight in any direction.

And Gaitskell:

Gezira was a land of mirage. At dawn in winter the horizon stood up like a pink cliff circling a giant hollow in which a curious reflection of light

The Gezira in detail

disclosed villages and fields beyond the range of normal sight it was a hard land. The few trees were thorny, and on hot, dry, windy days dust-devils turned to dust-storms, creating an inferno of flying particles like sandstorms in the desert.

However, for all its monotony and even hostility, this land has one remarkable advantage; it is relatively cheap to irrigate. This is because of certain properties of the clay soil. Being impervious, clay allows the construction of canals which do not require expensive lining with concrete. Although water does seep into the subsoil, there is very little loss by this means. Indeed, it rarely seeps much deeper than a few centimetres.

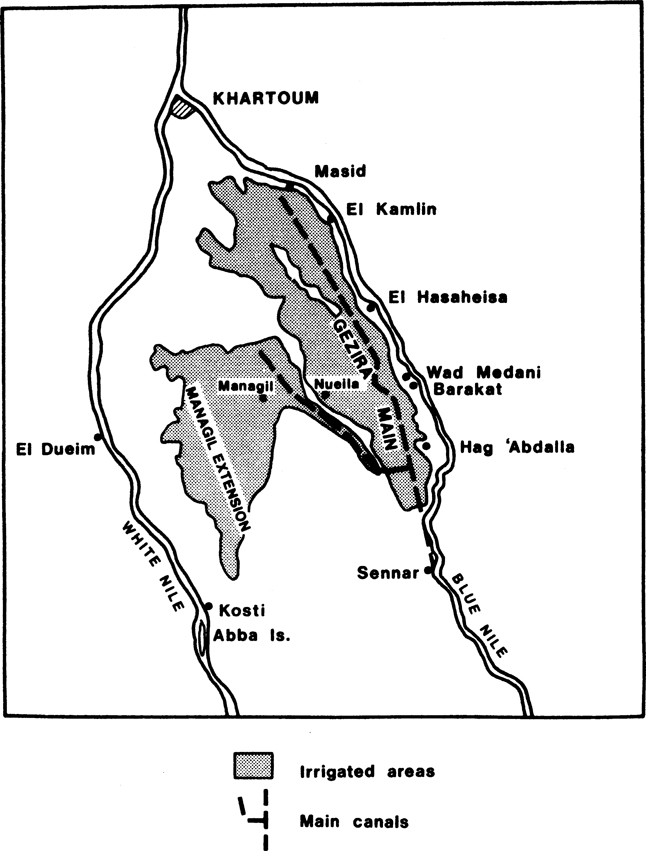

Other properties of the Gezira plain make it admirably suited to the development of gravity irrigation. From the Blue Nile, the entire area slopes gently downwards towards the north and west. This made the siting of the canal system relatively easy, the mean slopes varying between 1: 5,000 to 1: 10,000. Further, a slight ridge runs from Hag Abdalla to Masid () along the eastern edge of the Scheme. The main canal from the dam at Sennar follows the line of this ridge, thus giving good command over the whole area.

But, because of the low rainfall, the area could only be used for intensive farming under an irrigation regime. Rainfall in the Gezira is erratic and varies from the north to the south. In the north it averages somthing under 250 mm per year, rising in the extreme south to about 750 mm. Concentrated in the period from late July to early November, this pattern of rainfall enabled the people to create an economy based on the cultivation of dura (Sorghum vulgare) prior to the coming of irrigation. This subsistence grain economy was combined with the semi-nomadic herding of cattle and sheep.

Why was the Gezira Scheme built?

The history of the Gezira Scheme has been described in some considerable detail elsewhere. For this reason little would be gained from a detailed recapitulation of that history. However, certain points do need to be made here.

Gaitskell sees the creation of the Gezira Scheme under the management of British commercial companies (the Sudan Plantations Syndicate (SPS) and later also the Kassala Cotton Company (KCC)) with the aid of a large loan guaranteed by the British Government, as having been a fortunate coincidence. It was in his opinion a remarkable example of development achieved by combining the entrepreneurial spirit of private enterprise with the paternalistic spirit of colonial government. Indeed he skates over the reasons for the establishment of the Gezira Scheme in a brief discussion of why the cotton manufacturers pressure group in the United Kingdom, the British Cotton Growers Association, wanted to establish cotton growing in the Sudan. He says:

The failure of the American and Egyptian crops in 1909 brought home to Lancashire Spinners the peril of relying on these two countries, especially for the longer and finer cotton then increasingly demanded for better quality yarns.