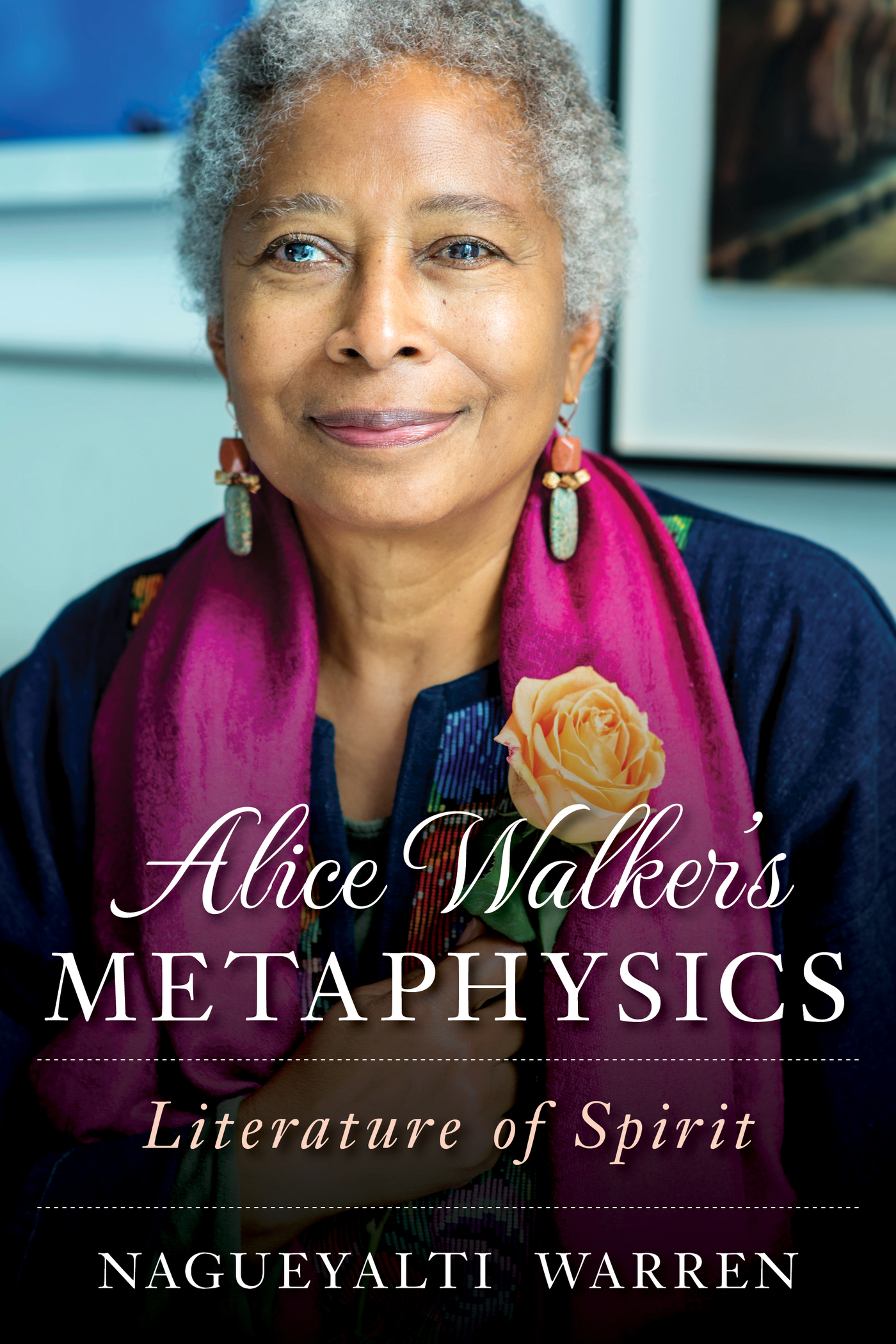

Alice Walkers Metaphysics

Alice Walkers Metaphysics

Literature of Spirit

Nagueyalti Warren

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2019 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Warren, Nagueyalti.

Title: Alice Walkers metaphysics : literature of spirit / Nagueyalti Warren.

Description: Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018039278 (print) | LCCN 2018039292 (ebook) | ISBN 9781538123980 (Electronic) | ISBN 9781538123973 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Walker, Alice, 1944Criticism and interpretation. | Metaphysics in literature. | Spirituality in literature.

Classification: LCC PS3573.A425 (ebook) | LCC PS3573.A425 Z895 2019 (print) | DDC 813/.54dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018039278

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

To Rueben C. Warren

and for our progeny,

Alkamessa, Asha, and Ali

Acknowledgments

I am deeply appreciative of the help received in the completion of this book. I sincerely thank my friend and colleague Sally Wolff-King for her sharp eye and helpful suggestions. The Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Librarys archivist, Gabrielle Dudley, was tremendously supportive. I am thankful for the efforts of my late friend and colleague, Rudolph P. Byrd, along with the wizardry of curator Randall K. Burkett, for successfully bringing the complete Alice Walker archive to Emory University Libraries in 2009.

In my circle of sustainers, special thanks to Rev. Mary Louise Ruffner for spiritual wisdom, and to Delores P. Aldridge and Vera Rorie for our break-out days for having fun. For your friendship and support, I will always be grateful.

Introduction

In 1982, Alice Walker published The Color Purple. Within weeks, the novel made the New York Times best-seller list and catapulted her to fame. The book was Walkers third novel. My first encounter with her work occurred that same year, when I lived in Jackson, Mississippi. In a bookshop off I-55, I purchased a copy of The Color Purple to take along on a trip to the beach. The store clerk asked if I knew Alice Walker, and informed me that Walker had once lived in Jackson; I had not known that fact. I had intended to read the book on the ride down to the Gulf Coast, but out of curiosity, I decided to read a few pages the night before. I finished the book that night and read it again at the beach. Thus, began my long journey in reading Alice Walker.

By the time the movie, The Color Purple, was released, I had read all of Walkers books; we had moved away from Mississippi, and in the firestorm of criticism that followed the release of Spielbergs movie, I began offering a seminar on Walkers novels. My course at Fisk University was the first to examine the works of a single female author, and my 1992 course, titled Reading Alice Walker, was the first at Emory University to concentrate on a single black woman author. This book is the culmination of thirty years of reading, studying, and teaching Alice Walkers work.

I believe that Walkers oeuvre, from its beginning, presents a metaphysical interpretation of life. The blindness in her right eye that resulted from a childhood injury surely helped to produce the insight that emerges in her works. From the time she was eight years old and disfigured by what she calls a patriarchal wound inflicted by her older brother Curtis, by her own admission she has felt like an outsider. Once outgoing and vivacious, Walker became shy and withdrawn; yet her solitude provided the space for developing what became her piercing perceptiveness about herself and others. Readers often dismiss Walkers nonlinear approach to history, and the luminal dimensions of reality that her writings expose, and focus instead on the clearly political content. Nonetheless, even her politics and activism reveal a metaphysical and deeply spiritual essence.

Walkers poetry is the chthonic root of her emergence as a writer. Many of her poems are reflective of her experiences, and some provide the cast for her fictional characters. Her collective works of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and childrens books shift the paradigm from a dualistic perception of life as good and evil to a forward-looking and optimistic view for those readers brave enough to remain open to the infinite possibilities that she presents. The message from her work is that we live in a spiritual universe. Everything is Spirit. We are all connected. Walkers works push the boundaries to insist that we includes humans, plants, animals, the earth, water, the air. Her concept of God, a word with Christian connotations, is more often referred to as Great Spirit, situating it closer to Native American and other traditional beliefs.

In Walkers works, Spirit is love, pure and unadulterated. This loving Spirit is alive, omnipresent, and awaits our recognition. No judgmental God in heaven waits for us to die, kills us, or condemns us to an everlasting hell. Walker does not embrace Christology, such as the womanist theologians discuss. Jesus is both human and Divine, as is everything. Life is everlasting. It changes form; therefore, people and all things appear to die only to transition into another form, in what some may see as reincarnation, although Walker herself does not use the term. Walkers character Lissie Lyles is the fictional representation of eternal life. She does not privilege the Bible as holy, but respects books in general.

Walker dramatizes life through a comic rather than a tragic lens. Defining tragedy and comedy, ecocritic Stephen OLeary states: Tragedy conceives of evil in terms of guilt; its mechanism of redemption is victimage, its plot moves inexorably toward sacrifice and the cult of the kill. Comedy conceives of evil not as guilt, but as error; its mechanism of redemption is recognition rather than victimage, and its plot moves not toward sacrifice but to exposure of fallibility. Walker exposes evil as erroneous thoughts and actions. Human agency as choice dominates her works. The agency that some people want to ascribe to God or to the devil belongs entirely to human beings. Within the comic paradigm, a moral ambiguity exists, whereas in tragedy a schism emerges between good and evil with no room for ambiguity. No open-ended possibilities are available.

Classified as a feminist, womanist, bohemian, white liberals lackey, and practically called, according to her, everything but a child of God, claims, the mystic experiences Spirit as immediate and present in all things, then mysticism is a worldview that aligns with Walkers writings.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.