2020 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Publication of this book was supported by funding from the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy Faculty Research Fund.

Excerpts appear from The Collectivist Roots of Madam C. J. Walkers Philanthropy by Tyrone McKinley Freeman on Black Perspectives (the blog of the African American Intellectual History Society), May 20, 2019, https://www.aaihs.org/the-collectivist-roots-of-madam-c-j-walkers-philanthropy/. Reprinted by permission of Black Perspectives.

Portions of chapter 5 originally appeared in T. Freeman, The Big-Hearted Race Loving Woman: Madam C. J. Walkers Philanthropy While Living in Indianapolis, Indiana, 19111914, in Hoosier Philanthropy:Understanding the Past, Planning the Future, edited by Greg Witkowski (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, forthcoming). Reprinted by permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Freeman, Tyrone McKinley, 1973 author.

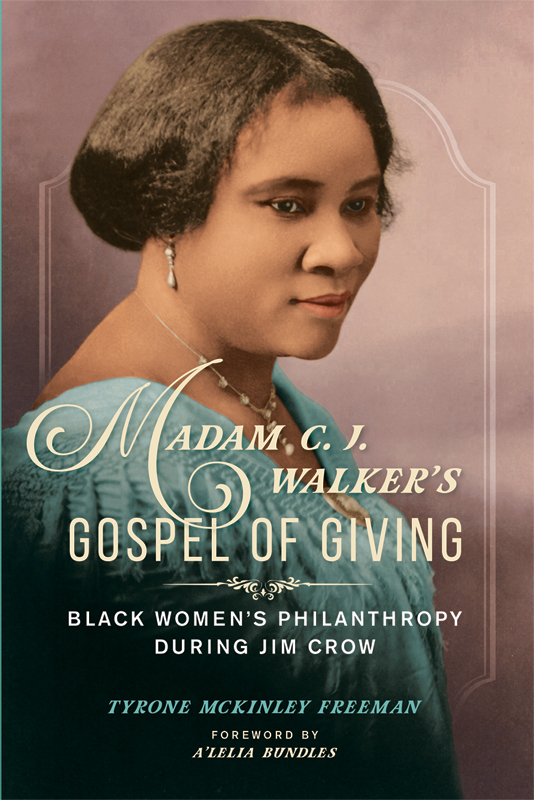

Title: Madam C. J. Walkers gospel of giving : black womens philanthropy during Jim Crow / Tyrone McKinley Freeman ; foreword by ALelia Bundles.

Description: Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2020. | Series: The new black studies series | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020013474 (print) | LCCN 2020013475 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252043451 (cloth) | ISBN 9780252085352 (paperback) | ISBN 9780252052330 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Walker, C. J., Madam, 18671919. | African American women executivesBiography. | Women philanthropistsUnited StatesBiography. | Cosmetics industryUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC HD 9970.5. C 672 F 74 2020 (print) | LCC HD 9970.5. C 672 (ebook) | DDC 338.7/66855092 [ B ]dc22

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020013474

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020013475

To Michelle, Olivia, and Alexander.

For all of

the generous churchwomen-clubwomen-educator-philanthropists

who have raised, taught, and loved me, especially Mom.

Foreword

ALelia Bundles

Tyrone McKinley Freemans philanthropic biography of Madam C. J. Walker significantly expands our knowledge beyond her well-known role as an early-twentieth-century hair-care entrepreneur and places her on the continuum of black philanthropy from Colonial American benevolent societies to the transformative twenty-first century giving of billionaire Robert Smith.

In Madam C. J. Walkers Gospel of Giving: Black Womens Philanthropy during Jim Crow, Freeman sets out to redefine who counts as a philanthropist and what counts as philanthropy. He questions conventional wisdom and asks us to reconsider the boundaries that have constricted our understanding of a vaunted American tradition.

As a philanthropic foremother of black generosity, Freeman shows how Walker emulated traditional nineteenth-century African American philanthropic practices and then created her own model by seeding early-twentieth-century fundraising in her community with leadership gifts once she had the means to do so.

While placing Walker within the historical context of American philanthropy, Freeman challenges us to reexamine the criteria that rely almost exclusively on wealthy white nineteenth-century male benefactors as standard bearers. He argues that a singular focus on industrialists like Andrew Carnegie skews our analysis and casts a vast philanthropic shadow. By this metric, Madam Walkers accomplishments are obscured and erased when compared with the philanthropy of men whose lives were not circumscribed by the sexism and the racist Jim Crow laws and customs she endured.

While one cannot study the history of African Americans without encountering their philanthropy, Freeman notes, it is unfortunate that one can study the history of philanthropy without encountering African Americans.

He seeks to correct this record and to capture the richness of African American volunteering, collective action, and financial contributions while dispelling the notion that African Americans are primarily recipients of philanthropy rather than agents of it. Indeed, income inequalityand disposable income for philanthropyin America remains stark. In 2016 the typical black familys net worth of $17,100 was about one-tenth that of a white household, according to The Dynamics of the Racial Wealth Gap, a 2019 study by two Federal Reserve Board economists. Focusing solely on the monetary value of a philanthropic gift, Freeman writes, reinforces the notion that African Americans have a tradition of being helped but not a tradition of helping.

By centering the origins of Walkers philanthropy on her membership at St. Pauls African Methodist Episcopal Church in St. Louis during the late 1800s, Freeman links her to black philanthropys roots in African societies as well as to black womens traditions of collective giving in missionary societies, fraternal orders, and national advocacy organizations that benefited black women and families.

Freeman shows how Walker's philanthropy evolved from small charitable gifts to larger, more transformative contributions that both connected her to her philanthropic forebears and set her apart from her contemporaries. As a poor widowed mother and washerwoman when she first arrived from Louisiana in 1888, she was a recipient of the largesse of others. Later, as a member of St. Pauls Mite Missionary Society, she helped collect pennies and nickels. As she became more prosperous, she gave to orphanages, retirement homes for the formerly enslaved, and needy neighborhood families near her Indianapolis factory. As a wealthy woman, she amplified the original giving model by hosting events for black suffragists, sponsoring war-bond drives during World War I, helping to retire the mortgage on Frederick Douglasss home in the Anacostia neighborhood of Washington, DC, and commissioning paintings by William Edouard Scott and John Wesley Hardrick, two renowned black Indianapolis artists.

Her annual convention of Walker Beauty Culturists provided an opportunity to advance her business as well as her philanthropy and political activism. She prioritized financial giving by awarding monetary prizes to the sales agents whose local clubs had contributed the most to charity. Despite their limited personal financial resources, Walker helped them use their activism, advocacy, and service as a gateway to giving. Today we call this time, talent, and treasure.

I want my agents to feel that their first duty is to humanity, Walker told her delegates in 1917, as large numbers of African Americans were migrating from the rural south to northern cities. I shall expect to find my agents taking the lead not only in operating a successful business, but in every movement in the interest of our colored citizenship.