IMAGES

of America

MADAM WALKER

THEATRE CENTER

AN INDIANAPOLIS TREASURE

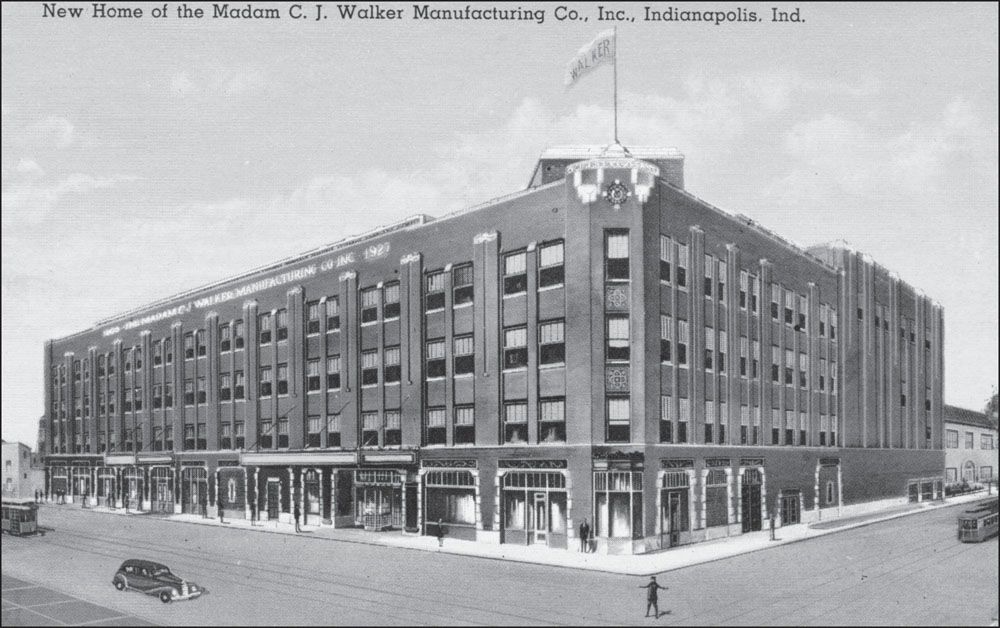

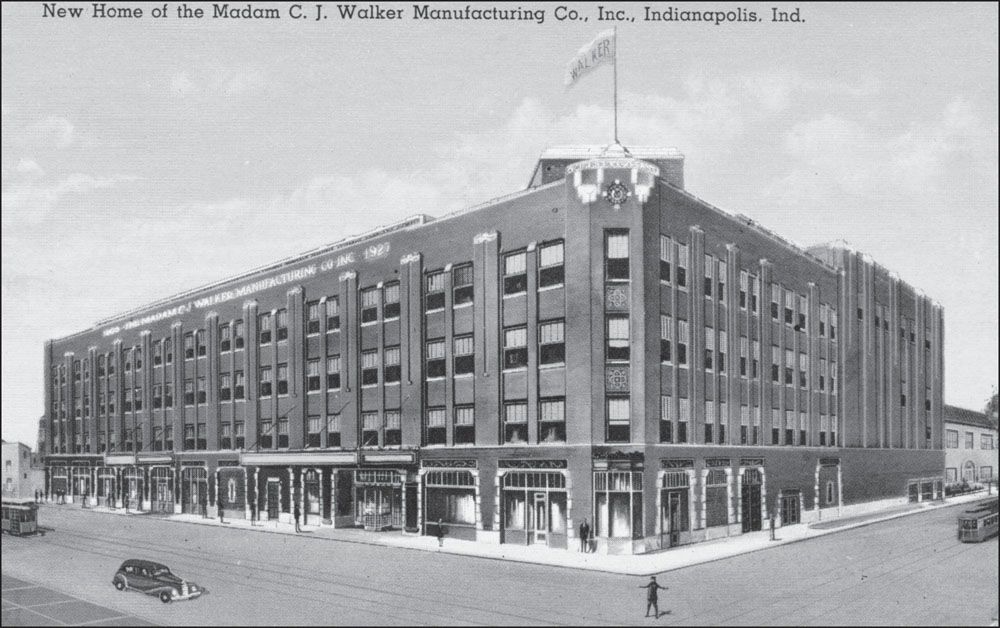

PROMOTING A NEW HEADQUARTERS, 1927. During the yearlong construction of its headquarters, the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company began distributing postcards with an architects colorful pastel version of the building to publicize the expansion. (Courtesy of Madam Walker Family Archives.)

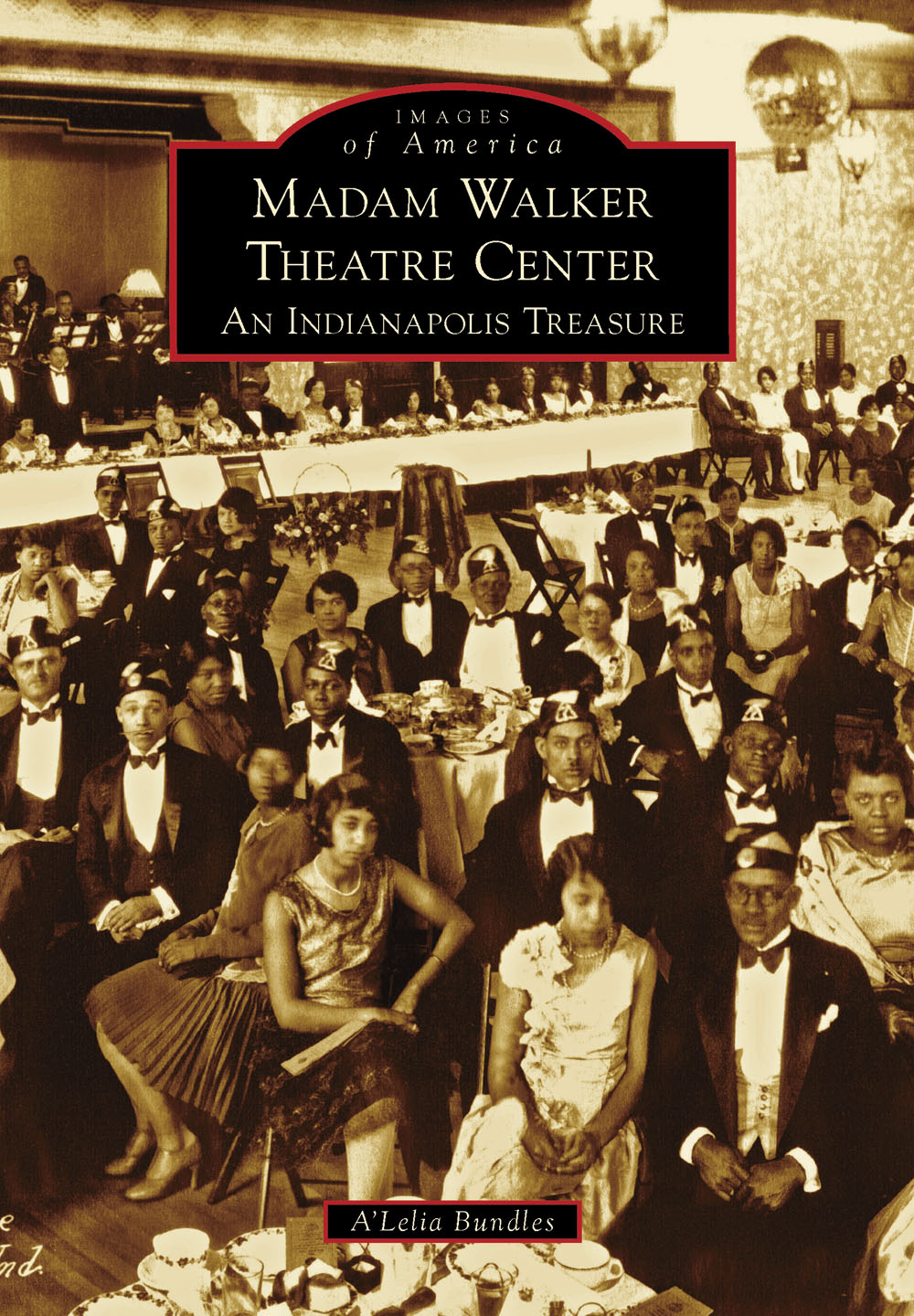

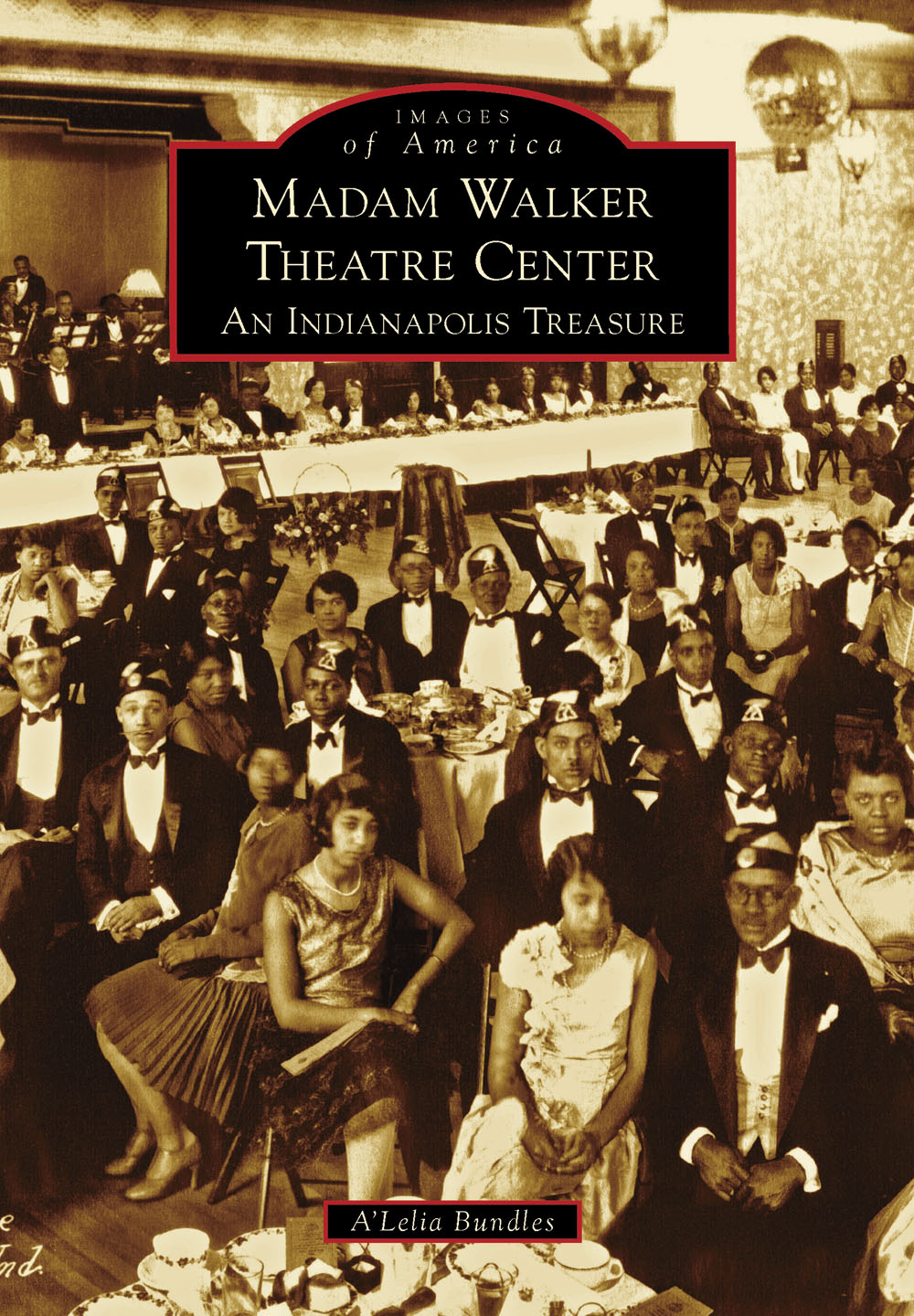

ON THE COVER: THE BOHEMIAN CLUB OF INDIANAPOLIS. The Bohemian Club of Indianapolis, known for its elegant annual dinner dances, hosts one of the first events in the newly opened Madam Walker Buildings Grand Casino Ballroom in February 1928. To ensure nonstop live music, the organization usually hired two orchestras. See . (Courtesy of Madam Walker Theatre Center.)

IMAGES

of America

MADAM WALKER

THEATRE CENTER

AN INDIANAPOLIS TREASURE

ALelia Bundles

Copyright 2013 by ALelia Bundles

ISBN 978-1-4671-1087-7

Ebook ISBN 9781439644133

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013937113

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

This book is dedicated in memory of my grandfather Marion R. Perry Jr. and my mother, ALelia Mae Perry Bundles, with thanks to my father, S. Henry Bundles, who still knows the stories.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The sheer joy of perusing hundreds of photographs reminds me of the incredible accomplishments not only of my great-great-grandmother Madam C.J. Walker but also of the founding generation of Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company employees. Without Madam Walker, her daughter ALelia Walker, attorneys F.B. Ransom and Robert L. Brokenburr, factory manager Alice Kelly, secretary Violet Reynolds, Walker Beauty School national supervisor Dr. Marjorie Stewart Joyner, and bookkeeper Marie Brooks Overstreet, there would be no story to tell.

I am fortunate that my grandfather Marion R. Perry preserved most of the photographs that now comprise the Madam Walker Family Archives and that Violet Reynolds lived long enough to shepherd the donation of a trove of materials from the Walker Estate trustees to the Indiana Historical Society.

I thank my late mother, ALelia Mae Perry Bundles, for encouraging me to tell the Walker story, and my father, S. Henry Bundles, for continuing to provide historical tidbits that otherwise would be lost.

Judith Ransom, Jill Nelson, Stanley Nelson, and Robert Ransomdescendants of Walker general manager F.B. Ransomeach play a critical role in keeping the legacy alive. Special thanks also go to Wilma Moore, senior archivist of African American history at the Indiana Historical Society, for her intimate knowledge of the Walker papers, and to Thomas Ridley, the Walker Theatres much-loved resident docent.

Many foundations, corporations, and individuals have supported the Madam Walker Theatre Center (MWTC) in its present incarnation as a performing arts center. The Lilly Endowment of Indianapolis deserves special gratitude as do members of the MWTC board and staff who have worked so diligently through the years.

For photographs not in my personal collection, I thank the Museum of the City of New York; Malina Jeffers of Mosaic City; Jimmy Beard; Alan Ray; Charlene Cox; Tony and Lucy Reynolds; Cordelia Wills; Alpha Blackburn; Gina Woods; Richard McCoy; Walt Thomas; Paul Mullins and Lewis Jones of Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis (IUPUI); and Susan Sutton and John Herbst of the Indiana Historical Society. This book benefits greatly from the photographs of Carl Black, William Rasdell, and John Hurst, who continue to chronicle MWTC events.

INTRODUCTION

Step inside the historic Madam Walker Theatre and savor the magic. Nearly nine decades of African American entertainersfrom blues queen Mamie Smith to Motown legend Smokey Robinsonhave performed on its stage.

Designed in 1927 as the new headquarters of the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company, the Walker Building is one of the few remaining Indiana Avenue structures from the days when the area vied with Memphiss Beale Street and Chicagos Bronzeville as well-known hubs of African American business and entertainment. Both a National Historic Landmark and an Indiana State Historic Landmark, it serves as a reminder of the Walker Companys place as one of the most successful black-owned American businesses of the first half of the 20th century.

Its founder, Madam Walker, was born Sarah Breedlove in 1867 on the same Delta, Louisiana, cotton plantation where her parents had been enslaved until the end of the Civil War. Orphaned at seven and widowed at twenty, she spent much of her adult life as a laundress in St. Louis. After concocting formulas for a shampoo and ointment that healed scalp disease when she was in her late thirties, she founded a company that eventually would train and employ thousands of women. By the time she died in 1919, she had parlayed her hair care products enterprise and savvy New York real estate investments into a million dollars worth of assets. The Guinness Book of World Records has cited her as the first self-made American woman millionaire.

Drawn to Indianapolisknown as the Crossroads of Americanby its relatively prosperous black business community and its well-connected transportation network, Madam Walker moved her company headquarters there from Pittsburgh in 1910. Quickly involving herself in the citys civic, business, and religious life, she joined Bethel AME Church, donated $1,000 to the new Senate Avenue YMCA, and became a member of the local National Negro Business League chapter.

In 1914, just as she had done on many occasions, Walker visited the Isis Theatre in downtown Indianapolis. To her surprise, the young white ticket booth operator informed her that admission for colored people had increased to 25, though it remained 15 for white customers. Refusing to pay the escalated price, Walker returned to her office and instructed her attorney to sue the Isis. Legend has it that she also vowed that day to build her own movie theater.

Although the Walker Building was completed eight years after her death, Walker had purchased the triangular-shaped lot not long after the Isis Theatre incident. The four-story, block-long flatiron building, located at 617 Indiana Avenue, originally was planned to house her corporate headquarters and factory. By the time the doors opened in December 1927, it had become much more. It was a forerunner of todays shopping malls with a drugstore, a beauty salon, a beauty school, a restaurant, professional offices, a ballroom, and a 1,500-seat theater.

Added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1991, the Walker Building makes Indianapolis one of the few American cities able to claim such tangible evidence of its African American cultural and entrepreneurial history. Chicagos original Regal Theatre, built in 1928, was razed in 1973. Tom Honest John Turpin opened St. Louiss Booker Washington Theatre in 1913, but it closed in 1930. Like the Walker, the Lincoln Theatre in Washington, DC, which opened in 1922, has been restored. Harlems Apollo, which maintained a whites-only policy until 1934, has been a premier venue for black artists for eight decades. But the Walker stands alone among these three remaining theaters because an African American company originally built it.

Next page