Prologue

Madam C. J. Walkers story has always deserved an expansive loom on which to weave the threads of her legendary life with the broad themes and major events of American history. As my great-great-grandmothers biographerand as a journalist who loves a well-told storyI consider it to be my good fortune both that she was born in 1867 on the plantation where General Ulysses S. Grant staged the 1863 Siege of Vicksburg and that one of her brothers joined other former slaves in the 1879 mass exodus to the North from Louisiana and Mississippi. I could not have fabricated a more perfect scenario than her confrontation with Booker T. Washington at his 1912 National Negro Business League convention or her 1916 arrival in Harlem on the eve of Americas entry into World War I. I could not have invented her 1917 visit to the White House to protest lynching or her decision to build a mansion near the Westchester County estates of John D. Rockefeller and Jay Gould. Certainly when I learned that she had been considered a Negro subversive in 1918 and had been put under surveillance by a black War Department spy, I was convinced that reality indeed was more interesting than most fiction.

It has surely been a bonus for me that Madam Walker knew so many of the other African American luminaries of her time because the work of their biographers has provided invaluable guidance. From the correspondence, papers and books of antilynching activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett, educators Mary McLeod Bethune and Booker T. Washington, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People executive secretary James Weldon Johnson, Crisis editor W.E.B. Du Bois, labor leader A. Philip Randolph and others, I have been able to resurrect long-forgotten relationships.

As a pioneer of the modern cosmetics industry and the founder of the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, Madam Walker created marketing schemes, training opportunities and distribution strategies as innovative as those of any entrepreneur of her time. As an early advocate of womens economic independence, she provided lucrative incomes for thousands of African American women who otherwise would have been consigned to jobs as farm laborers, washerwomen and maids. As a philanthropist, she reconfigured the philosophy of charitable giving in the black community with her unprecedented contributions to the YMCA and the NAACP. As a political activist, she dreamed of organizing her sales agents to use their economic clout to protest lynching and racial injustice. As much as any woman of the twentieth century, Madam Walker paved the way for the profound social changes that altered womens place in American society.

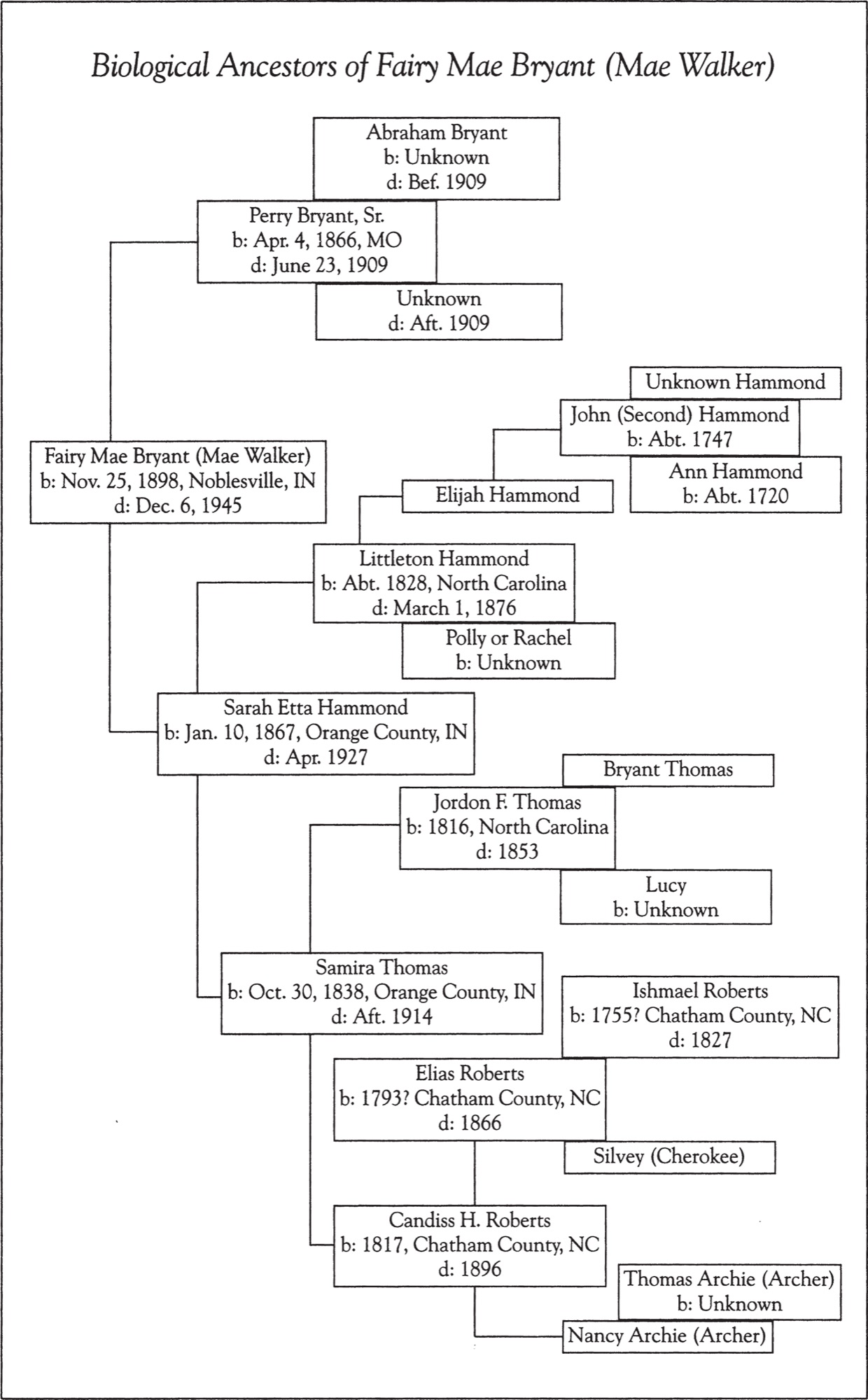

My personal journey to write On Her Own Ground, the first comprehensive biography of my great-great-grandmother really began before I could read. The Walker womenMadam, her daughter ALelia Walker and my grandmother Mae Walkerwere already beckoning me at an early age, sometimes whispering, sometimes clamoring with the message that I must tell their story. In a faint childhood memory, their spirits envelop me in filtered gray light beneath a tall window inside my grandfathers apartment. On a nearby dresser, just beyond my reach, I can see their sepia faces inside hand-carved frames.

Even as a little girl I sensed that these grandmothers belonged not only to me but to the world and to those who would claim them for their own dreams and fantasies. Black history books had long recited the outlines of Madam Walkers classic American rags-to-riches rise from uneducated washerwoman to international entrepreneur and social activist, from daughter of slaves to hair care industry pioneer and philanthropist. Poet Langston Hughes crowned ALelia Walker the joy-goddess of Harlems 1920s. The Negro press fancied MaeALelias adopted daughter and only legal heira tan Cinderella. By the time I discovered the Walker womens public mythology, they had already begun to draw me into the world of their private truths.

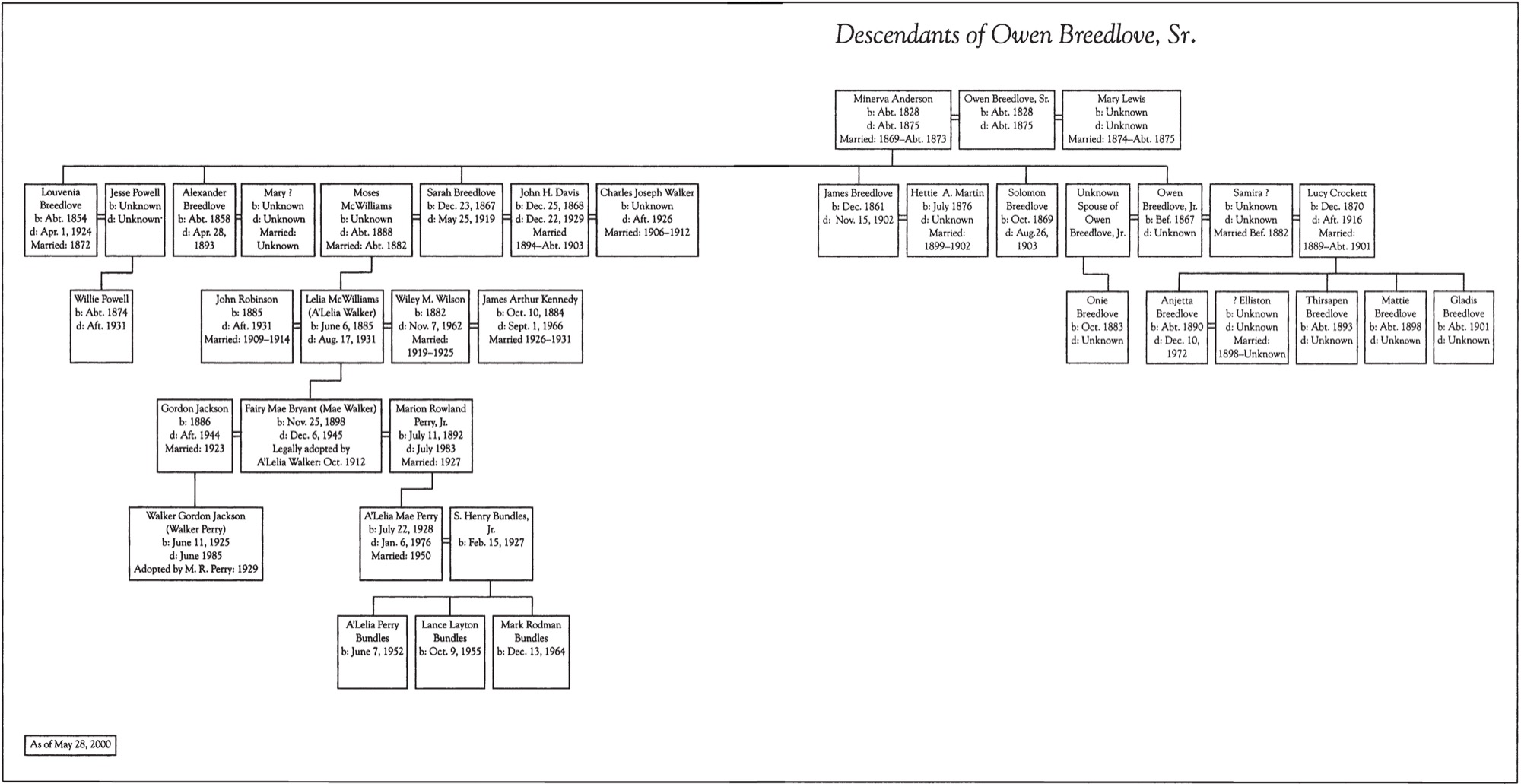

My grandfather, Marion Rowland Perry, Jr., first met Mae during the summer of 1927 at Villa Lewaro, Madam Walkers lavish Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, mansion. A handsome young attorney and World War I army officer, he was quite proud of a lineage that included college-educated parents. Mae was a recent divorce and the future Walker heiress, whose thick, waist-length hair had helped sell thousands of tins of Madam C. J. Walkers Wonderful Hair Grower. That weekend, ALelia Walker invited Marion to the Cotton Club with her friendsand without Maeto take the measure of the man she considered a potential son-in-law. She discreetly slipped him a hundred-dollar bill to gauge his comfort with paying large tabs. Apparently he passed her test, for a few weeks later, on August 27, he and Mae drove to Port Chester, New York, in his green Pierce-Arrow to be married by a justice of the peace. The following July, my mother, ALelia Mae Perry, was born.

In 1955, when my mother, my father, S. Henry Bundles, and I moved to Indianapolis, I was three years old and Mae had been dead for nearly a decade. For a few weeks while we waited to move into our house, I slept in a bedroom of my grandfathers apartment surrounded by Maes personal treasures. I remember that, in the months afterward, whenever Pa Pa opened his front door to greet us, the gluey aroma of roast lamb, Lucky Strikes and old-man musk coated my nostrils. In the entryway, as my mother knelt to adjust my hair bow and smooth my three long braids, my eyes always fixed upon a tall, moss-green Chinese lacquer secretary. Letters, keys, stamps and paper clips tumbled from its tiny gold-trimmed drawers and secret cubbyholes. A serene Ming Dynasty maiden stood guard on the door of its locked upper cabinet. Even before I learned it had belonged to Madam and the first ALelia, I was tempted by its mysteries.

Beyond the foyer, the apartment rambled down a long, hushed hall. At one end, Pa Pas sleeping alcove opened onto a sitting room crammed with the Walker womens belongingsALelias first editions of Jean Toomers