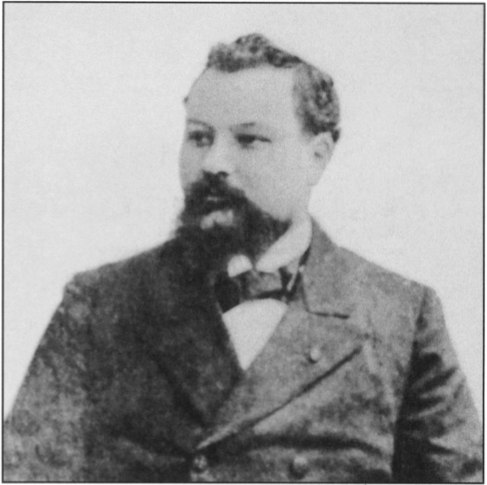

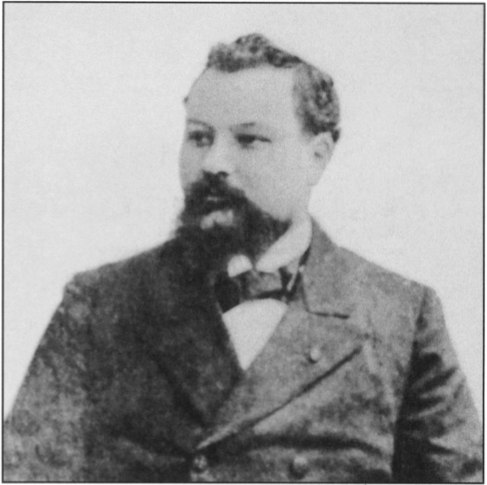

The French physician, Papus (Gerard Encausse, 18651916) was involved in many secret societies, and was in a unique position to synthesize these influences into his astrological and esoteric work. His mentors included Francois Charles Berlet, the French astrologer involved in the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor, and Thomas Burgoyne, author of The Light of Egypt, the book that explained the practices of the Hermetic Brotherhood. Initiation Astrologique was published in France posthumously in 1920, and made available material used by European esotericists early in the 20th century.

First published in 1996 by

Samuel Weiser, Inc.

P. O. Box 612

York Beach, ME 03910-0612

Copyright 1996 Samuel Weiser, Inc.

Introduction copyright 1996 J. Lee Lehman, Ph.D.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recordingtaor by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Samuel Weiser, Inc. Reviewers may quote brief passages.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Papus, 18651916.

[Initiation astrologique. English]

Astrology for initiates : astrological secrets of the western mystery tradition / Papus ; translated by J. Lee Lehman.

p. cm

Originally published: Paris : vend Se La Sire, 1920?

Includes bibliographical references (p. 127) and index.

ISBN 0-87728-894-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Astrology. I. Title.

BF1701.Pl713 1996

133.5dc20

96-28287

CIP

BJ

Typeset in 11 point Palatino

Printed in the United States of America

04 03 02 01 00 99 98 97 96

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984.

www.redwheelweiser.com

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TRANSLATOR'S INTRODUCTION

A beginning is the time for taking the most delicate care that balances are correct.

Frank Herbert, Dune

T HE FRENCH PHYSICIAN PAPUS (Grard Encausse, 1865-1916) is best known to English-speaking readers for his work, The Tarot of the Bohemians. However, his influence in late 19th-early 20th-century France was much greater. To understand his position, and the significance of this work, we must weave together several themes: occultism in the late 19th century and astrology in the same period. Several significant tributaries join the river that was occultism then, and several emerge into the delta of the late 20th-century New Age.

If we begin our examination a bit before the time of Papus, we can note that the end of the 18th century marked a considerable uptick of interest in occultism corresponding to the archaeological successes in Italy, the Middle East, and Egypt, led primarily by British, German and French teams. Finally, through the Rosetta stone, Egyptian hieroglyphs became comprehensible to the West. In Italy, Roman life in all its pagan glory was being unearthed at Pompeii and Herculaneum. The sites of Troy and many biblical locales emerged. The Western mind confronted the Paganism so thoroughly repressed by Christianity, just as British and Dutch explorers and traders in the East were making Buddhist, Hindu, and Taoist material available in the West on a massive scale. Following the breakdown in the hegemony of the Catholic Church, for the first time in 1,500 years, it became possible

Elsewhere I have detailed how this influx of knowledge and ideas spawned two New Ages: what I called the Enlightenment New Age in the 18th century, and then, in 1848, the Spiritualist New Age. Briefly, the Spiritualist New Age, which began in the great year of revolutions historically, brought home the immediate idea that death was but a curtain that could, under certain circumstances, be penetrated, at least for purposes of communication.

This pair of New Ages extended across national boundaries in ways that are only now being reestablished. For one thing, the European bias toward multilingual education was still pronounced; for another, many leading practitioners roamed freely between the various European countries, even including America or Asia in their itineraries. Spiritualism itself had begun in the United States, migrating quickly to Europe through such practitioners as Mrs. Hayden and D. D. Home. Enthusiasts in different countries insured that significant works in any language were rapidly translated and transmitted to students of any other language.

Meanwhile, France had its indigenous Spiritualism through the work of Alphonse Cahagnet on his celestial telegraph. Spiritualism had definite forerunners internationally in mesmerism and crystal scrying, but it only became wildly popular through the coming of the seance.

Later in the century, during the 1870s, interest shifted from communicating with the dead, to the meaning of life in the here-and-now, and also the hereafter. Three major streams Besides these three groups, myriad people and groups styled themselves as Masonic orders, Rosicrucians, or other ancient titles. It was common for individual seekers to accumulate a long pedigree of ranks and memberships in secret, or not-so-secret societies.

During this period, the fate of astrology had differed on the Continent, in England and America. It is overwhelmingly tempting to label the 17th century as the end of the several millennia1 period of Classical Astrology. The 17th century featured some of the greatest minds of the field: William Lilly, Nicholas Culpeper, Richard Saunders, Placido de Titus and Jean Morin (Morinus), not to mention a second tier that, in almost any other century would be considered the lights: John Gadbury, Richard Edlin, William Ramesey, John Goad and Henry Coley, to name a few.

The 17th century marked the final integration of the idea of the heliocentric solar system, and the victory of scientific materialism as the predominant meta-view of the day Astrology's fortunes declined markedly in England and the United States in the 18th century, although there is evidence that horary and electional astrology remained popular in port cities This subsequent revival, begun popularly by Raphael I and the Mercuri, was of an astrology vastly simplified, often lacking the power to predict. By making a virtue of necessity, British astrology passed from being unable to predict very well to being unwilling to predict at all, in the acceptance of psychological astrology, with its taboos that proscribe activity (such as prediction) that might be seen as impinging on the exercise of free will.

The Continent did not see such extremes in astrological crash and burn in the 18th century, and so Continental astrology saw fewer radical changes in fortune in the 19th century.

Knowledge of astrology had long been considered essential to occult learning, being the basis of timing and attribution in alchemy and ritual magic. Its importance to 19th-century occultists increased considerably as archaeological evidence accumulated, which suggested a worldwide primitive state of star worship, or astrolatry. During this period, one could easily assert the belief that astrolatry was the first major world religion. Thus, astrology became not merely the timepiece of ritual, but the basis for understanding many religious ideas.

The principal of the H. B. of L. in France was Francois Charles Barlet, who also just happened to be

Next page