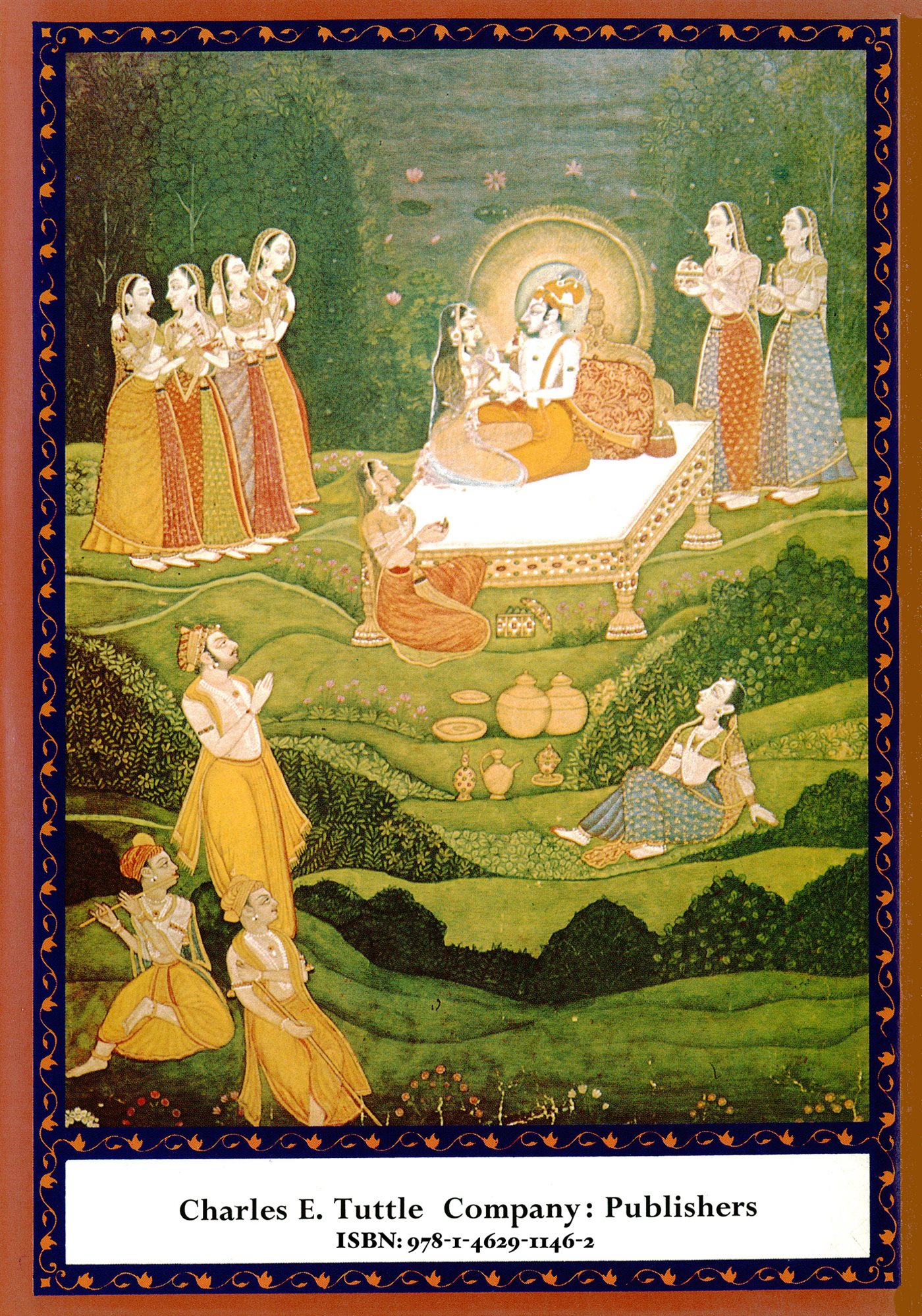

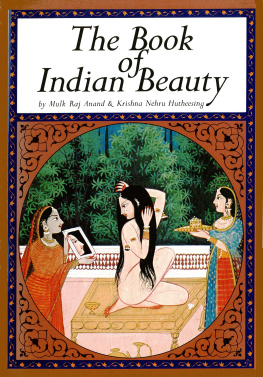

Mulk Raj Anand - The Book Of Indian Beauty

Here you can read online Mulk Raj Anand - The Book Of Indian Beauty full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Tuttle Publishing, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Book Of Indian Beauty

- Author:

- Publisher:Tuttle Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Book Of Indian Beauty: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Book Of Indian Beauty" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Book Of Indian Beauty — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Book Of Indian Beauty" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

| THE BRIDE |

Thy well-combed hair, thy splendid eyes with their arches curved almost to thine ear, thy rows of teeth entirely pure and regular, thy breasts adorned with beautiful flowers....

Thy body anointed with saffron and thy waist belt that puts the swans to shame.

Moon-faced, elephant-hipped, serpent-necked, antelope footed, swan-waisted, lotus-eyed.

ANONYMOUS

LIKE EVERYTHING else the ideal of female beauty has been defined in India in charming aphorisms and poems.

The myth that unfolds the story of creation-about how woman came to be-is more decorative still. Man was first created and woman next. And Brahma, the creator, fashioned the feminine form better than the masculine. As for the process of creation itself, Brahma had finished making man and came to the molding of woman. He discovered to his consternation that he had exhausted all the solid materials. Whether that happened by accident or design is not known, but it is well that it was so, for what use would solid man have had for a solid woman?

Brahma, however, was very resourceful. He took the curve of the creepers outside his house, and gave woman her gracefulness of poise and carriage. Her breasts he modeled on the round moon, endowing them with the softness of the parrot's bosom. To her eyes he gave the glance of the deer. On her complexion he imprinted the lightness of the spring leaves. He shaped her arms with the tapering finish of the elephant's trunk. Into her general make-up went the indescribably tender clinging of the tendrils, the trembling of the grass, the slenderness of the reeds. Then he swathed her whole form with the sweetness of honey and the fragrance of choru flowers. Her lips he treated with the essence of ambrosial nectar.

Too timid and too shy She is ever averse to meet her lord, She is called a Navodha or newlywed by those Learned and experienced in the lore of love.

Too timid and too shy She is ever averse to meet her lord, She is called a Navodha or newlywed by those Learned and experienced in the lore of love.

(Motiram in Rasa Raj)

The actual life of woman in India has been less than the metaphorical ideal and more sordid.

The old mud house in the village lies behind the gnarled trees of a grove, shrinking from a too-living sun, seemingly the same today as yesterday and a thousand years ago. Strange growths oppress its riven sills, and across its carved wooden doors a spider weaves its web. Beyond the tall porch of the hall, beyond the men's room, across the huge, sunlit courtyard, shadowed by a veranda with pointed arches, supported by wooden pillars, stand the women's apartments, curtained off from the rest of the house by strips of coarse sackcloth and hiding dusky forms that glide to and fro, swathed in fine homespuns. The floors sag under the fall of heavy, unshod feet. The walls and ceilings enclose here the mute prayer of a lady, spent and wrinkled, there the steady droning of the churning wheel and the babble of many young voices.

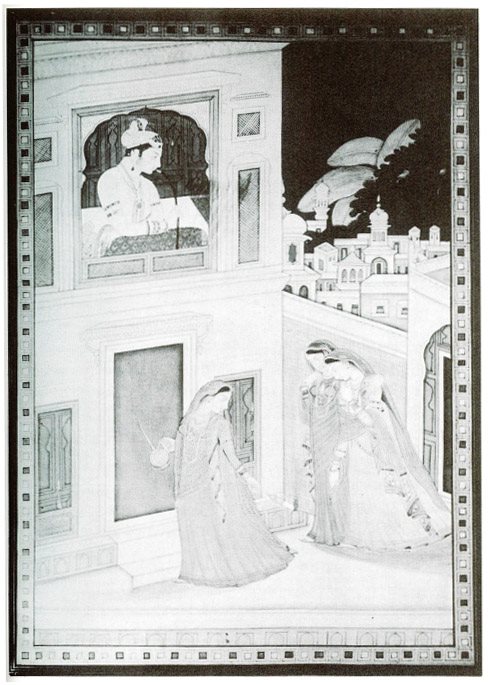

2. Bride being led to her lover. Kangra, c. 1800.

Somewhere in the dark chambers is heard the wailing chant of a young bride. She is beautiful or she is plain, but she has made the best of those gifts that life has bestowed on her, through sringar, or simple toilette, the rules of which have come down as habit from generation to generation. She does this sringar because it is part of a ritual that almost every woman practices. As a girl she was not allowed to embellish her charms overmuch. And, consequently, there is a certain self-consciousness in her attempt to adorn herself, a self-consciousness accentuated by her desire to shine. Also inhibiting her is the fear of a mother-in-law only too insistent on the demands of duty and responsibility, a woman who dictates rules of conduct about everything-about beauty and love and marriage, about all the inflated ideals of womanhood in India.

Endless were the considerations that governed her marriage: religious, social, philosophical, and astrological. All the ingenuity of priests exercised itself in discovering a man whose horoscope revealed potentialities that tallied with the scroll of the young girl's fate. Worldliness could not have exerted itself more than in her parents' choice of the bridegroom.

For months, preparations for the marriage had been going on. At length the day arrived when the sacred ceremony was to be performed. From early dawn, throughout the morning and afternoon, the ritual of the bride's toilette proceeded with slow, deliberate care, in the interminable details of the process of adornment: the ablutions in medicated waters; the anointment of the body with scented oils, cosmetics, and unguents; the plaiting of the hair and the weaving of it into patterns, decking it with ornaments of gold and flowers; the adorning of the parting of the hair with oxide of lead ( sindhur); the rubbing of various creams on the face, and the use of powders compounded of scented ingredients; the imprinting of marks on the forehead; the painting of moles on the chin; the application of collyrium ( tutiya) to the eyes; the tinting of hands and feet with henna; and the last little touches of perfume.

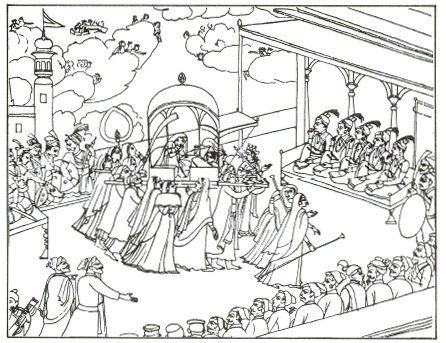

3. Swayamvara, detail. Pahari, late 18th century.

After the performance of intricate ceremonies to the rhythms of holy chants, this doll-like creature enters the home of her mother-in-law. There, life unfolds some of its implications to her. She seeks the beauty and ecstasy of union and realizes its difficulties and despairs. But, gradually, she accepts the daily round, giving forth sons, as was expected of her, until in her own turn she becomes a mother-in-law.

From the perfumed womanhood

From the perfumed womanhood

Of loving night,

Night amorous ever

Tireless in her couplings

With the body of the world.

(From the Burmese, 19th century)

Obviously, woman in India has sometimes been exalted as a goddess, but mostly she has been pampered as a plaything or kept down and oppressed.

Love, in the form of the romantic impulse, so dominant a feature of the classical age, has become taboo to her except in rare cases; the only form of "love" recognized as valid traditionally has been the union of the sexes to beget a child-the duty to the unborn, to the inheritor of the traditions of the race, the ties of fatherhood and motherhood.

Indeed, the Brahmins have succeeded in exterminating the primordial instinct for emotive love in the married life of men and women.

From this reduction of the wife to the status of a slave, bound and fecund for the service of the hearth, the courtesan benefited greatly, as in the Greece of the 4th century and in the Rome of the Empire. For, as the wife was merely the servant, the courtesan was the ideal of romance. Fortunately, however, the Indian courtesan since remote antiguity has borne little resemblance to the modern street woman, a fallen creature and outcast. On the contrary, the courtesan was the custodian of music and dance and love, accomplished actress, inspirer of poets, sculptors, and painters, friend of kings-to whom she gave good counsel in peace and armies of men in war.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Book Of Indian Beauty»

Look at similar books to The Book Of Indian Beauty. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Book Of Indian Beauty and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Anita Anand - The Library Book. Anita Anand ... [Et Al.]](/uploads/posts/book/40194/thumbs/anita-anand-the-library-book-anita-anand-et.jpg)