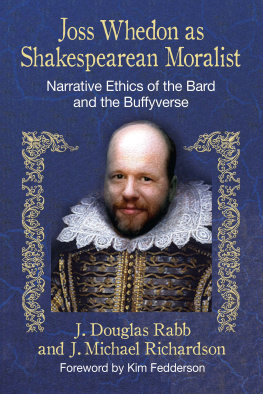

Joss Whedon as Shakespearean Moralist

Narrative Ethics of the Bard and the Buffyverse

J. Douglas Rabb and J. Michael Richardson

Foreword by Kim Fedderson

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

ALSO OF INTEREST

Indian from the Inside: Native American Philosophy and Cultural Renewal, 2d ed., by Dennis H. McPherson and J. Douglas Rabb (McFarland, 2011)

The Existential Joss Whedon: Evil and Human Freedom in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, Firefly and Serenity, by J. Michael Richardson and J. Douglas Rabb (McFarland, 2007)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1786-2

2015 J. Douglas Rabb and J. Michael Richardson. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any formor by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopyingor recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system,without permission in writing from the publisher.

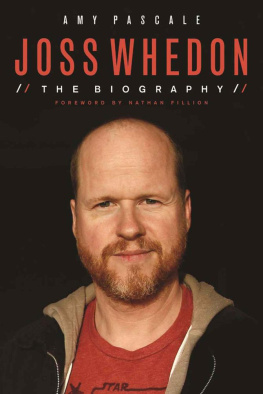

On the cover: Whedon as Shakespeare by Mark Nisenholt, professor of visual arts, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kim Fedderson for the kind words of the foreword, and to Mark Nisenholt for his cover art Whedon as Shakespeare. Both, in their own way, capture rather well the main themes of the book.

We want to thank Rhonda W. Wilcox, co-editor of Slayage: The Journal of the Whedon Studies Association, for encouraging us in our studies of Whedon. As we will show, the very fact that there is a Whedon Studies Association supports our contention that Whedon is the Shakespeare of our time.

We also thank Rhonda for permission to use, as we have, our 2009 Slayage paper, Myth, Metaphor, Morality and Monsters: The Espenson Factor and Cognitive Science in Joss Whedons Narrative Love Ethic, Slayage: The Online International Journal of Buffy Studies, 7.4 (28) 2009, and her own Let It Simmer: Tone in Pangs, Slayage: The Journal of the Whedon Studies Association, 9.1 (33) 2011.

Foreword

by Kim Fedderson

Joss Whedon is the Shakespeare of our time. The authors make a bold claim, one that their intended readers, who, depending upon their perspectives on the tensions between popular and high culture, contemporary and traditional dramatic forms, innovation and adaptation (not to mention the level of their interest in vampires, werewolves, and apocalyptic science fiction), will variously celebrate, deride, but, most certainly, debate.

What does Whedons being Shakespeare entail? J. Douglas Rabb, a philosopher with a long-standing interest in the moral imagination and the co-author of the influential Indian from the Inside: Native American Philosophy and Cultural Renewal (with Dennis H. McPherson, 2d ed., McFarland, 2011), and J. Michael Richardson, a colleague of mine at Lakehead University with whom I have collaborated extensively on Shakespeare in popular culture, are in an excellent position to address this question. They are perhaps best known for The Existential Joss Whedon: Evil and Human Freedom in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, Firefly and Serenity (McFarland, 2007), one of the earliest book-length scholarly engagements with Whedons work.

In this new book, they argue that, like Shakespeare, Whedon is a writer whose works are highly imaginative, dramatically innovative, intellectually stimulating, and, despite, or because of, these features, have found a wide audience. Shakespeare continues to be the most widely produced writer of all time, and Whedons audience continues to expand: his recent film, The Avengers, is one the highest grossing pictures of all time. Rabb and Richardson present a rich catalogue of Whedons direct borrowings from Shakespeare: bits of dialogue, characters (inclusive of a claim that Beatrice from Much Ado About Nothing is Buffys precursor), plot motifs, and allusions to The Merchant of Venice, Othello, Macbeth, Measure for Measure, and The Tempest. The affinities between the two extend beyond mere borrowings. Whedon, they contend, is Shakespeare-like in his manner as well as his matter. Both have a significant impact on their respective cultures. Like Shakespeare, Whedon coins new words (his penchant for -y suffixes, as in angsty, or -age suffixes, as in slayage), and these are finding their way into the language. Both establish themselves in emergent genres, embraced by popular audiences but frequently held in less regard by contemporary cultural arbiters. While auteurs, both are comfortable with the collaborative contributions of others. Both rely upon companies of actors whose roles in previous performances seep into new roles. Both employ meta-theatrical turns, inviting audiences to glimpse the ethical meanings beneath the surface of the texts.

This concern for ethics and the role the imagination plays in ethical decision-making is the central focus of this book. Rabb and Richardson claim that Whedon, like Shakespeare, is a great ethicist. They contend both Whedon and Shakespeare compose narratives which provide what Kenneth Burke called equipment for living. The dramatized stories they tell have the potential to inform our ethical decision-making, influencing the choices we make as we try to secure a good life. Drawing on cognitive science, in particular the work of Lakoff and Johnson, Rabb and Richardson argue that metaphor (e.g., life as a journey) can capture the complexity of our experience and so inform our moral choices better than a series of abstract ethical precepts (the Ten Commandments) or principles (Mills utilitarian the greatest good for the greatest number, or Kants rationalist categorical imperative). They argue that the desire to establish transcendental universal ethical principles, good for all places and all times, is frustrated by the embodied nature of human experience. As brains with bodies, we engage in ethical decision-making always already situated in particularly concrete circumstances complexly determined by our geographical, historical, societal, and cultural locations. The imagination, which through metaphor and narrative is able to wed abstract tenor (e.g., justice) and vehicle (e.g., scales) eclipses reason in its ability to represent the complexity of embodied human experience; and in this respect, is better able to inform ethical-decision making than reasons abstractions which purchase their universality by the shucking off the particularity of worldly experience.

As an early modern, Shakespeares moral imagination presents us with worlds pushed out of joint, often as a consequence of excessive adherence to or willful transgression of societal codes and cultural customs, creating complex ethical dilemmas the implications of which frequently exceed the promise or hope of resolution afforded by comedys marriages and tragedys funerals. Whedon, situated in a postmodernity in which there is little or no consensus over what constitutes a world in or out of joint, makes TV shows and movies out of popular genres (e.g., teen horror, science fiction, comic book action heroes) which capture the irony and anxiety suitable to what some claim are these indeterminate, pre-apocalyptic or post-apocalyptic times.

Next page