Table of Contents

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Richardson, J. Michael.

The existential Joss Whedon : evil and human freedom in Buffy the vampire slayer, Angel, Firefly and Serenity / J. Michael Richardson and J. Douglas Rabb.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7864-2781-9

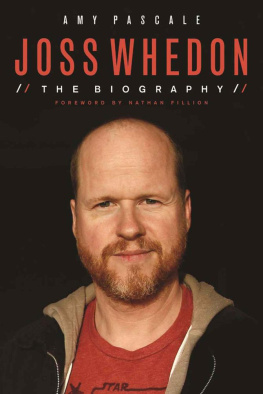

1. Whedon, Joss, 1964 Criticism and interpretation. I. Rabb, J. Douglas. II. Title.

PN1992.4.W49R53 2007

791.4302'33092dc22 2006034777

[B]

British Library cataloguing data are available

2007 J. Michael Richardson and J. Douglas Rabb. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

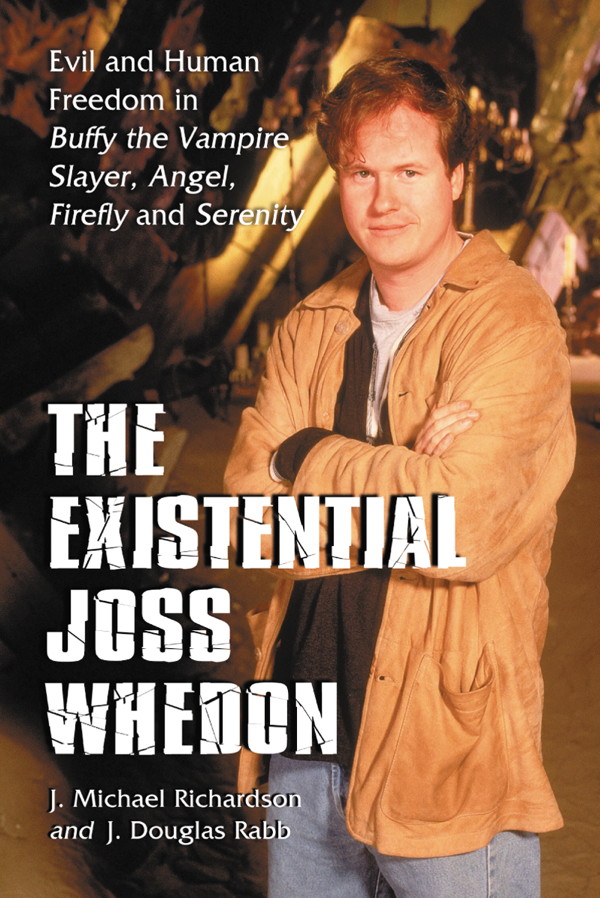

On the cover: Joss Whedon on the set of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, 1997 (WB Television/Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Introduction

Well, it sure aint no philosophy class, now, is it? Buffy the Vampire Slayer 3.5, Homecoming

In this study we examine the major works of contemporary American television and screen writer Joss Whedon, including Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, Firefly, and Serenity. We argue that these works are part of an existentialist tradition which stretches back from the French atheistic existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre (19051980), through the Danish Christian existentialist Sren Kierkegaard (18131855), to the Russian novelist and existentialist Fyodor Dostoevsky (18211881). Both Whedon and Dostoevsky, for example, seem preoccupied with the problem of evil and human freedom. Both argue that in each and every one of us a demon lies hidden (The Brothers Karamazov, 124). Whedon personifies these demons and has them literally wandering about and causing havoc in the fictional Southern California town of Sunnydale. He also introduces a Slayer to fight and subdue these personifications of evil: In every generation there is a Chosen One. She alone will stand against the vampires, the demons, and the Forces of Darkness. She is the Slayer... (Buffy the Vampire Slayer, opening). Given that the setting of Buffy is Southern California, it should not come as a great surprise that the Slayer turns out to be an athletic, fashion-conscious, blonde high school girl, called Buffy, who insists on referring to her sacred calling as slayage (the term can also denote the successful results of such activity). Dostoevsky, we contend, treats the subject only slightly more seriously. He does not personify our hidden demons in quite the same way. Rather, he refers to them as the demon of rage, the demon of lustful heat at the screams of the tortured victim, the demon of lawlessness let off the chain, the demon of diseases that follow on vice (124).

We thought that Whedon and Dostoevskys somewhat similar treatments of evil and human freedom just might be worth some serious study, particularly by scholars with our different but complementary academic training: a professor of philosophy and a professor of literature. As we got into this study, we suddenly found ourselves rewarded beyond our wildest expectations. During our research, we made a most extraordinary discovery. The popular philosophy of contemporary America and that of preMarxist Russia, represented in Dostoevskys writings, are so strikingly similar that it is possible to argue that they are in actual fact one and the same. Pre-Marxist Russia and contemporary America actually share the same philosophy, the same values and the same world views.

We fully realize that some may dismiss our claims about contemporary American philosophy because they are based in part on pop culture, on Joss Whedons popular television series, rather than on what goes on in the philosophy departments of American universities. For this reason, we should point out that the philosophy undeniably found in the novels and short stories of Fyodor Dostoevsky (arguably part of the popular culture of his day) was in striking opposition to the philosophy found in Russian universities of the time. In fact, from 1826 to 1889, philosophy instruction was either strictly forbidden or severely curtailed in Russian universities. For this reason, the Russian literature of the time is more than usually concerned with recurrent philosophical and quasi-philosophical problems (Kline, 258). In all his work Dostoevsky is particularly concerned with defending existential freedom and with rejecting the scientific determinism implicit in studies such as N. G. Chernyshevskis The Anthropological Principle in Philosophy (1860). We would certainly argue that the immense popularity of Dostoevskys writings at the time strongly suggests that he was able to strike a chord with his readers, and that he was saying something important, providing philosophical nourishment unavailable to them in their universities. This we take as evidence that the philosophy contained in these popular writings may be regarded as the popular philosophy, or at the very least, as a popular philosophy of his Russian readers. In a similar way, we argue that the immense popularity of Joss Whedons television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer as well as of the spinoff series Angel and the space westerns Firefly and Serenity suggests that Whedon, like Dostoevsky, has said something of importance to his generation, something not readily available in the educational establishment. This, we contend, is the popular philosophy of contemporary America. We will, of course, explain it in some detail as we develop our argument, looking briefly at other relevant writers and philosophers.

Despite the title of James Souths book, Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Philosophy, comparatively little has been written explicitly about the philosophy embedded in the series. In fact, despite the subtitle of Souths book, Fear and Trembling in Sunnydale, it contains not a word on either Kierkegaard or existentialism. Kierkegaard is perhaps best known for his book Fear and Trembling. There are, of course, a growing number of useful academic studies of Whedons work. For example, a number of essays published in Souths book and elsewhere look at Buffy through the eyes of a particular philosopher and seem to try to impose that philosophy on the Buffyverse, as the world of Buffy and Angel has come to be known. We argue, on the contrary, that the philosophy to be found there must be drawn from the text itself. In allowing the Buffyverse to speak for itself, we do make critical use of recent studies such as Gregory Stevensons Televised Morality: The Case of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Rhonda Wilcoxs Why Buffy Matters: The Art of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and Jana Riesss What Would Buffy Do?: The Vampire Slayer as Spiritual Guide, as well as numerous articles published in, for example, Slayage: The Online International Journal of Buffy Studies.

Compared to commentaries on the Whedonverse, very much more has been written about Sartres and Dostoevskys existential philosophies. Their work has, after all, been subjected to extensive critical scholarshipin Dostoevskys case, for something like 125 years. Explaining their existentialism is made somewhat less difficult because we have had so many studies to draw upon. We would point out that readers need not have read either Sartre or Dostoevsky, or any of the many commentaries on their work, in order to follow our argument here. The entire existentialist tradition culminating in Jean-Paul Sartre and, we contend, Joss Whedon can be traced back to Dostoevsky. As a foundation for our study we present and discuss a reading of Dostoevskys existentialism, by Russian philosopher Lev Shestov, which we argue has the interesting parallels to Joss Whedons work mentioned above. We begin, therefore, by attempting to do for Whedon what Shestov has done for Dostoevsky.

Next page