The Least Likely Man

The Least Likely Man

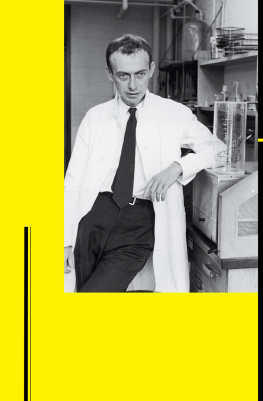

Marshall Nirenberg and the Discovery of the Genetic Code

Franklin H. Portugal

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2015 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Portugal, Franklin H., author.

The least likely man : Marshall Nirenberg and the discovery of the genetic code / Franklin H. Portugal.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-262-02847-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-262-32354-3 (retail e-book)

1. Nirenberg, Marshall W. 2. BiochemistsUnited StatesBiography. 3. GeneticistsUnited StatesBiography. 4. Genetic code. I. Title.

QP511.8.N57P67 2015

576.5092dc23

[B]

2014017232

In loving memory of my parents, Henrietta and Morris Portugal, and Sylvia and Sol Howard, who gave me Evelyn

Acknowledgments

In the three years it took to write this book, many people contributed their professional skills and/or reminiscences to make it all possible. I acknowledge with pleasure each and every one.

Family

Ana Bonnheim, Bonnie Bonheim, Malcolm Bonnheim, Noah Bonnheim, Joan Geiger, and Myrna Weissman.

Interviews

Bernard Agranoff, Bruce Ames, Samuel Barondes, Arthur Beaudet, Stanley Becker, Alvin Blocker, Rodney Blocker, James Boyles, Thomas Caskey, Brian Clark, Minor Judd Coon, David Davies, Gary Felsenfeld, Robert Gallo, Joseph Goldstein, Linda Greenhouse, Dolph Hatfield, Arthur Hillman, William Jakoby, Oliver Jones, Edward Kravitz, Karl Krueger, Philip Leder, Judith Levin, Richard Marshall, Robert Martin, Heinrich Matthaei, Matthew Meselson, Charles ONeal, Phillip Nelson, Alan Peterkofsky, Fritz Rottman, Alessandra Rovescalli, Edward Scolnick, Melvin Shader, Millicent Tomkins, Joel Trupin, Conrad Wagner, Arthur Weissbach, Herbert Weissbach, and Bernard Witkop.

James Watson and Sydney Brennerthe two living members of the RNA Tie Clubwere contacted for an interview for this book on a number of occasions. Unfortunately, James Watson was unavailable, and Sydney Brenner did not respond to my requests.

Libraries and Archives

Phyllis Andrews, University of Rochester; Frank Ascione, University of Michigan; Marcia Bassett, Barnard College; Jim Berry, Roger Tory Peterson Institute; Chip Calhoun, American Institute of Physics; Cynthia Cardona-Melndez, Orange County Regional History Center; John Carter, Columbia University; H. Frederick Dylla, American Institute of Physics; Jean Ferguson, Duke University Archives; Stephanie Gaub, Orange County Regional History Center; James Gehrlich, New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell; Gianna Gifford, Boston Public Library; Ana Guimaraes, Cornell University; Dane Guerrero, Hunter College; Victoria A. Harden, Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum; Barbara Faye Harkins, Office of NIH History; Alice Harmon, University of Florida; Julio L. Hernandez-Delgado, Hunter College; Karen L. Jania, University of Michigan; Garret B. Kremer-Wright, Orange County Regional History Center; Peggy McBride, University of Florida; Amy McDonald, Duke University Archives; Sharon C. Mathis, Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum; Nicole Milano, New York University; Christie Moffat, National Library of Medicine; Malgosia Myc, University of Michigan; Brian McNerny, Lydon Baines Johnson Library; Mary Frances OBrien, Boston Public Library; Mark Palmer, Alabama Department of Archives and History; Ludmila Pollock, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Tana M. Porter, Orange County Regional History Center; John Rees, National Library of Medicine; Emily Sanford, U. of Michigan; Crystal Smith, National Library of Medicine; Adam J. Stone, City College of New York; Paul Theerman, National Library of Medicine; Linda Todd, The Catholic University of America; Sara Van Arsdel, Orange County Regional History Center; Debra Wilkins, Alabama Department of Archives and History; and John Zarrillo, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

MIT Press

Christopher Eyer, Robert Prior, and Marcy Ross.

Museums

Normal I. Platnick, American Museum of Natural History; Ward Wheeler, American Museum of Natural History; and Marcia Jo Zerivitz, Jewish Museum of Florida.

Research and Transcription

Julius Adler, Falvia J. Arana, Laurence Auerbach, Edwin Becker, Margaret Boehm, Arielle Capurso, Sean Carroll, Christopher Cleary, Francis Collins, Mathew Daniels, Christopher Donohue, Matthew Dugandzic, Vicky Guo, Norma Zabriskie Heaton, Haruhiro Higashida, Kenneth Kreuzer, Peter Lengyel, Howard Markel, Judy Mermelstein, Jennifer Murduck, Toshiharu Nagatsu, Frank Nordllie, Joseph Perpich, Carlos Basilio Reyes, Alexander Rich, Steven Sabol, Alan Schechter, Shail K. Sharma, Phillip A. Sharp, William L. Smith, Vassiliki Betty Smocovitis, Harold Varmus, and Victor Vogel.

Thanks Go as Well to the Individuals Below

Yale Altman, Katherine D. Anderson, Robert Balaban, Otis Brawley, Cindy Cissel, Jack Cohen, Irwin Feldman, Hank Grasso, Bruce Howard, Evelyn Howard, Orest Hurko, Michael Kancher, Ian Lowe, Joseph E. Nascimento, Laura Patricio, Herman S. Paul, Daniel P. Scott, Mini Shader, Walter Reich, Victor Vogel, Marc-Denis Weitze, Morgan Woerner, and Phil Wolgel.

Any omission is inadvertent and very much regretted.

Introduction

Marshall Warren Nirenberg is the most famous person you have never heard of. In 1968, he shared the Nobel Prize for discovery of the alphabet of lifethe genetic code. That discovery has had an almost immeasurable impact, not just in science, but on society as a whole. It is the Rosetta Stone on which we interpret the 3.3 billion letters of DNA, the genetic material that makes us human.

Then why is Marshall so little known? In this book, that is one of several questions I have sought to answer.

And who really discovered the genetic code? That is an equally important question. Despite awarding the Nobel Prize to Marshall Nirenberg and others, that question continues to prove contentious. Matt Ridley, supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation in New York, claims Francis Crick was first. Who is right?

If Marshall was first, how and when did he do it? What makes the man who makes the ideas? Where did his ideas come from? When and how did they develop? How did he nurture them? What caused them to shrivel at times? How did they survive the stifling winds of competition? How, indeed, did he ever triumph?

No one in his entire life ever voted Marshall most likely to succeed. If he was understated, he was also constantly underrated. He was modest, perhaps to a fault. But he was also clever and creative. Marshall did something prescient, something somewhat unusual for a scientist. In addition to his lab notebooks, he kept a separate set of green, hardcover notebooks. Into those notebooks tumbled a steady stream of ideas, thoughts, and concerns. A careful reading of those entries has supplied much of the material on which this book is based. I have used that material to try to provide answers to the questions I have posed.

Rather than a broad view of science, I have used Marshall Nirenbergs story to illustrate how science gets done. This book is certainly not the first attempt to do so. But perhaps it takes a bit of a different tack. I have sought to provide a critical analysis of the various claims and counterclaims based on my own background as a scientist. Rather than simply depending on the reminiscences of men years after the fact regarding who was first to make each discovery, I have gone back to original source materials. What did they say and do at the time, not just what did they remember afterwards? I have included the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Next page