Table of Contents

Guide

Page List

THE SECRET

OF LIFE

[ Rosalind Franklin, James Watson,

Francis Crick, and the Discovery

of DNAs Double Helix ]

Howard Markel

In memory of

Dr. M. Deborah Gordin Markel

August 1, 1958October 16, 1988

A dedicated scientist whose life was heartbreakingly cut short by cancer

Contents

THE SECRET

OF LIFE

Toutes les histoires anciennes, comme le disait un de nos beaux esprits, ne sont que des fables convenues.

(All the ancient histories, as one of our wits has said, are but fables that have been agreed upon.)

VOLTAIRE

For my part, I consider that it will be found much better by all Parties to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write that history myself.

WINSTON CHURCHILL

Every schoolboy knows that DNA is a very long chemical message written in a four-letter language Of course, now that we know the answer, it all seems so completely obvious that no one nowadays remembers just how puzzling the problem seemed then In research the front line is almost always in a fog.

FRANCIS CRICK

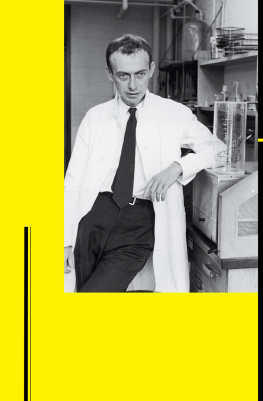

O n February 28, 1953, shortly after the chapel bells struck noon, two men hurtled down a stairwell of Cambridge Universitys Cavendish Physics Laboratory. Bursting with exhilaration, they had just made the scientific discovery of a lifetime and wanted to tell their colleagues about it. Reaching the ground floor landing first, with a loud thud, was James D. Watson, a twenty-five-year-old, wooly-haired biologist from Chicago, Illinois. One step behind him, and more careful in his descent down the steps, was Francis H. C. Crick, a thirty-seven-year-old British physicist from the hamlet of Weston Favell in Northampton.

If this moment was made into a Hollywood motion picture, we might begin with an aerial view of the University of Cambridge and move in to the lovely English gardens of Clare Collegewhere Watson once took his rooms. The camera then pans over the banks of the shallow Cam River, focusing briefly on a punter negotiating his narrow, square-bowed boat downstream. Next, we move across the backs, the magnificent lawns of Trinity and Kings colleges, before gazing upward at too many stone spires to count.

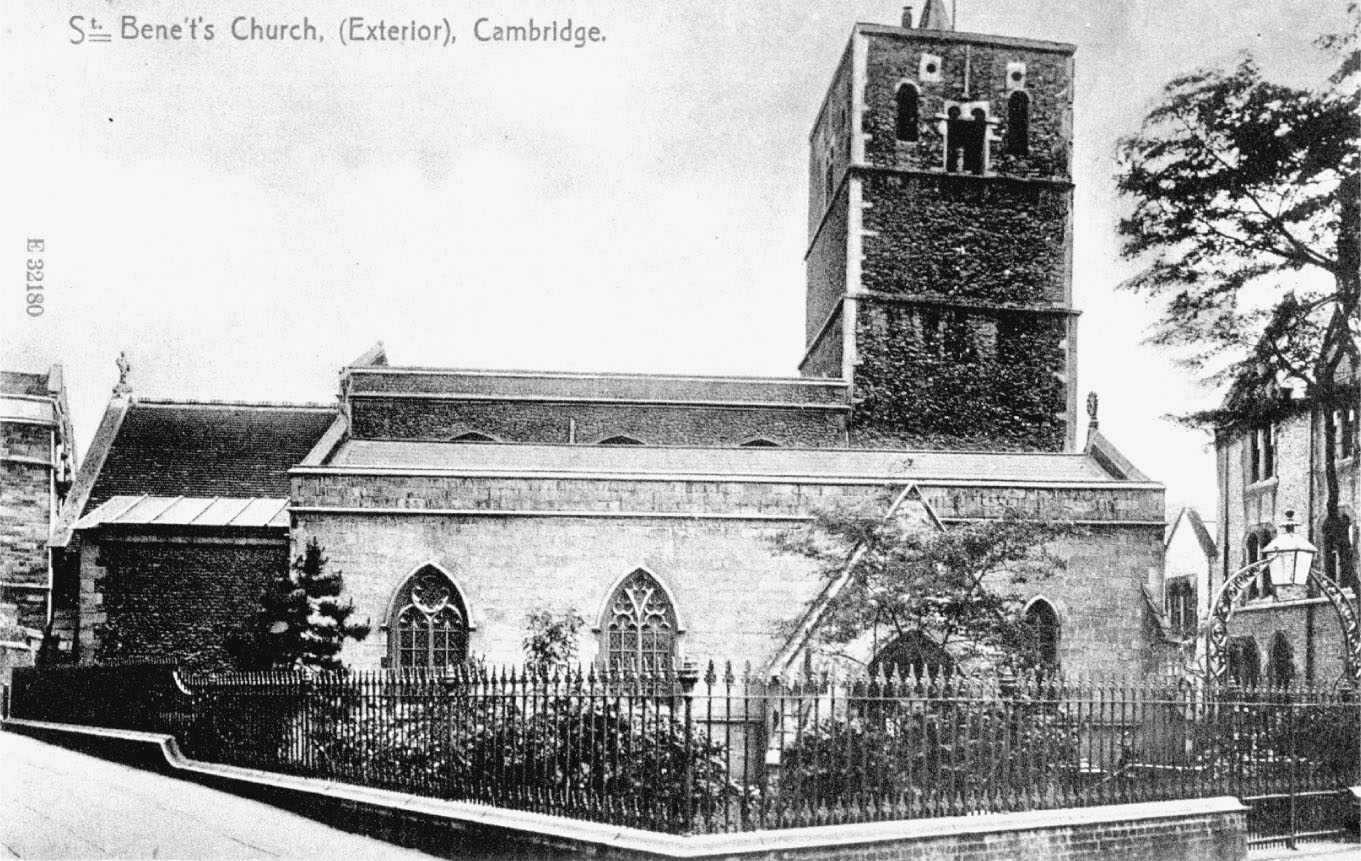

Our two scientists, now running breathlessly, ties askew and jacket tails flapping behind them, exit through the double Gothic-arched doors of the Cavendish Laboratory. They dash down Free School Lane, a short, winding path made up of irregular slabs of weathered flagstone. Rushing past a thicket of ancient trees obscuring St. Benets parish church, with its squat Saxon tower dating back to 1033, the two men dart around a wrought-iron fence cluttered with bicycles, the chief mode of transportation for many Cambridge students, fellows, and professors.

St. Benets Church, Cambridge.

The duos destination that breezy but unseasonably sunny afternoon was the Eagle pub. The Eaglea mere one hundred and one steps from the Cavendishfirst opened its doors on the north side of Benet Street in 1667. Known then as the Eagle and Child, the public houses major attraction was beer for three gallons a penny. It has been a favorite watering hole for Cambridge dons and students ever since. During the Second World War, the Eagle was the unofficial headquarters of the Royal Air Force units stationed nearby. In one of its rooms, a megillah of graffiti, doodles, and squadron numbers is drawn, burned, and scratched onto the walls. A now-forgotten pilot even managed to adorn the ceiling with a painting of a voluptuous, scantily-clad woman.

Six days a week, Watson and Crick lunched in a cozy salon sandwiched between the RAF Room and an oaken bar studded with the colorful pulls of stouts, ales, and lagers. On February 28, when they approached its doorway, panting and perspiring, the Eagle was already packed with academics tucking into steaming plates of bangers and mash, fish and chips, steak and kidney pie, and other noonday offerings. Between bites and sips, these brilliant men of Cambridge loudly debated nearly every aspect of the human condition.

The biologist and the physicist were there to make even more noise. They had just worked out the double helix structure of deoxyribonucleic acid, better known as DNA. Francis winged into the pub, shouting at the top of his voice, We have discovered the secret of life!

The Eagle pub.

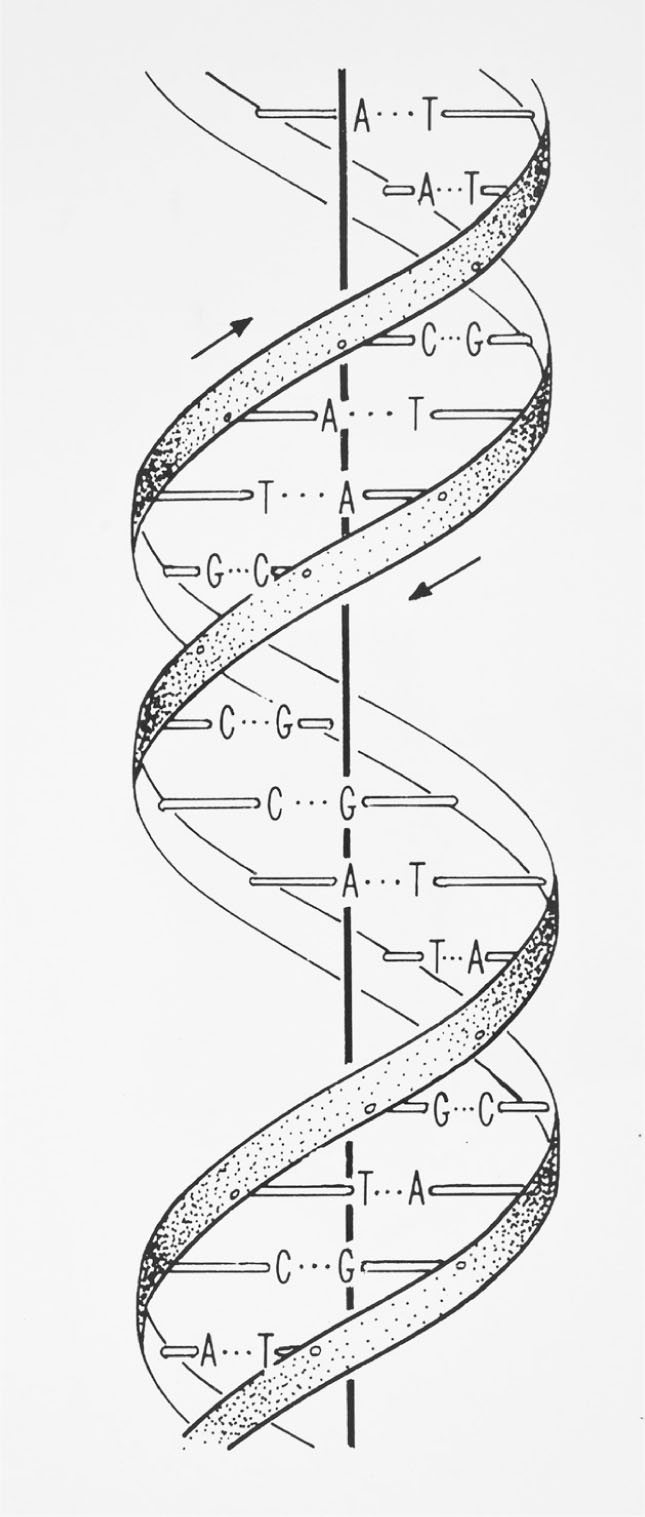

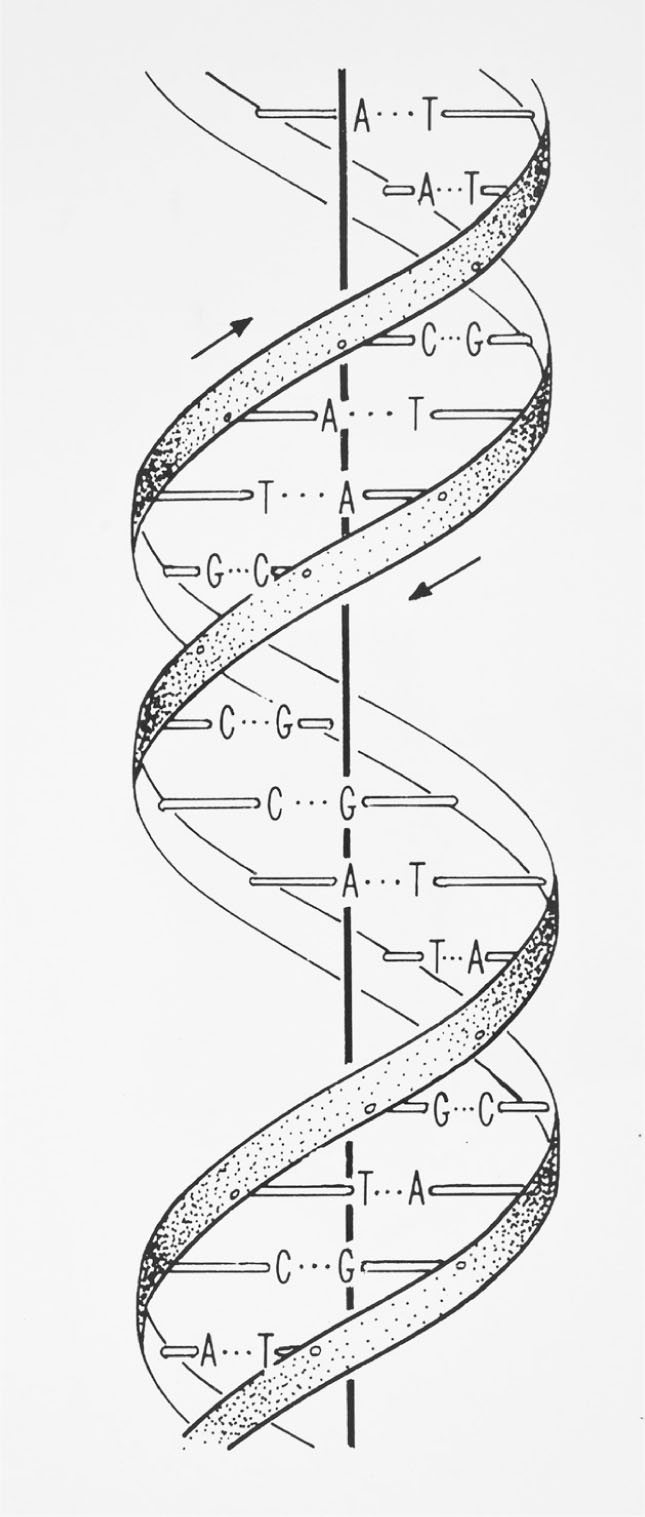

Schematic illustration of the double helix. The two sugarphosphate backbones twist about on the outside with the flat hydrogen-bonded base pairs forming the core. Seen this way, the structure resembles a spiral staircase with the base pairs forming the steps. (Artist: Odile Crick, 1953).

Boasting of this sort was looked down upon among the scholarly tribes of Cambridge, a code to which Crick only occasionally subscribed. Yet it is indisputable that on this particular day Watson and Crick did discover the secret of life, or, at least, its central biological secret. Their elucidation of DNAs structure followed a centuries-old dictum, which continues to this very day: one must determine the structure, or anatomy, of a biological unit before being able to fully understand (and manipulate) its function. When it comes to DNA, virtually every advance in our modern understanding of how genetic information is carried is predicated on this foundational discovery. We can say, without fear of contradiction, that February 28, 1953, represents a light-switch moment in the history of sciencefor that matter, in human history, period. Once that switch was turned on, nothing about our understanding of heredity, the life sciences, and the body was ever the same again. Everything changed, as if emerging from an age of darkness into one of total illumination.

The elucidation of the double helix explained the central role DNA plays as a single, living cell divides into two new cells, each containing and manifesting a copy of the parental DNA. The building blocks of DNA are called nucleotides; each one consists of a sugar, or carbohydrate, attached to a phosphate group (a phosphorus atom bound to four oxygen atoms) and a nitrogen base. The nitrogen bases in DNA are classified chemically as purines and pyrimidines. We now know that the purines (guanine and adenine) in one helical chain are hydrogen-bonded with complement pyrimidines (cytosine and thymine) in the other, creating the stairs to a spiral staircase. Its dual railings, or backbones, are the connected sugar and phosphate groups. This molecule, joined with billions more DNA molecules, contains within its double helical structure a precise order of purine and pyrimidine bases.