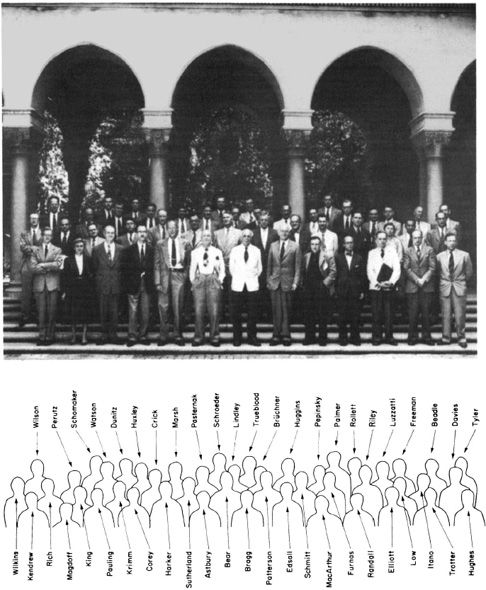

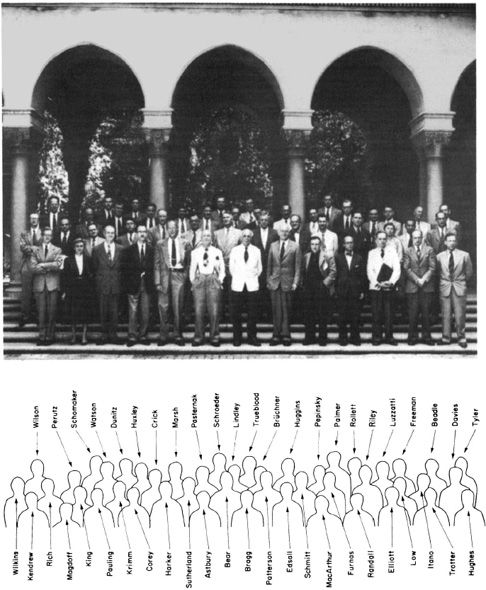

I Frontispiece. Pasadena Conference on the Structure of Proteins 21 to 25 September 1953.

THE PATH TO THE

DOUBLE HELIX

The Discovery of DNA

ROBERT OLBY

Professor of the History and Philosophy of Science

The University of Pittsburgh

FOREWORD BY

FRANCIS CRICK

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

MINEOLA, NEW YORK

Copyright

Copyright 1974, 1994 by Robert Olby.

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 1994, is an unabridged, corrected and enlarged republication of the work published by the University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1974 (published in the U.K. by The Macmillan Press, London, 1974). For the Dover edition, to which the subtitle The Discovery of DNA has been added, the author has corrected a number of typographical errors, corrected and expanded the bibliography, added death dates to entries in the Index where applicable and feasible, and provided a new Note to the Introduction and Postscript.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Olby, Robert C. (Robert Cecil)

The path to the double helix: the disovery of DNA/Robert Olby.

p. cm.

Originally published: Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1974.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-68117-7

ISBN-10: 0-486-68117-3

1. Molecular biologyHistory. 2. Dna. I. Title.

QH506.045 1994

574.873209dc20

94-3665

CIP

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

68117303

www.doverpublications.com

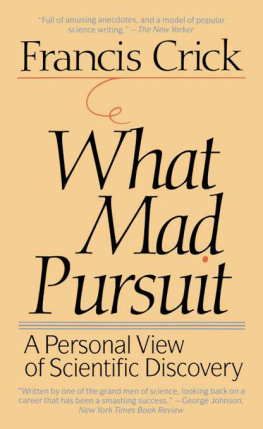

It is a pleasure to write a foreword to The Path to the Double Helix. As the reader will easily discover for himself it contains a fascinating series of related scientific histories told in a lively, perceptive and scholarly way. In spite of my overfamiliarity with parts of the story I have found it absorbing reading.

It is inevitable that comparisons will be made between this book and Jim Watsons earlier volume, The Double Helix , in spite of their obvious differences. Watsons book was really a fragment of his autobiography. Not only did he attempt to describe the discovery of the DNA through the eyes of the young man he was at that time but he included many lively personal details not strictly essential to his main theme. His , for example, relating how he lay on the floor at Carradale (the book was dedicated to Naomi Mitchison) and attempted to grow a beard tells us little of purely scientific interest. But then Watsons principal aim was to show that scientists were human, a fact only too well known to scientists themselves but apparently not, at that time, to the general public. Hence the books enormous success. Even if the science could only be glimpsed it sounded exciting and the gossip was irresistible.

To achieve his aim Watson could not avoid simplifying the scientific side of the story. Indeed it is surprising how many technical arguments he managed to slip in without making his text too heavy. It is also clear, as Medawar has pointed out, that Watson is not really interested in history as such. His interest lies in the futurein what will soon be discoveredbut time, in this case, has turned his future into his past and like the Ancient Mariner he could not rest till he had relived his story by communicating it.

Robert Olby has set himself quite different aims. As a historian of science he is interested in both the science and the history. This is not to say that he is in any way indifferent to personality. Who can resist the story of the ultrashy Fred Griffith being tricked into a taxi by his friends in order to get him to attend a meeting, or the picture of Darlington, during a rough night in mid-channel, teaching Bernal all the genetics and cytology anyone needs to know. The character of Maurice Wilkins, in particular, seems to me to come over more vividly in Olbys book than in Watsons, partly due to Wilkins letters which Olby has often quoted in toto. This is no accident. It springs from Olbys care and industry in collecting original documents and taping interviews, together with a good eye for a striking incident or a telling phrase.

The major difference between the two books, which is clearly reflected in the greater length of the present volume, is that Olby treats the science more thoroughly and at a higher intellectual level; in addition, he traces both the ideas and the methods back to earlier periods. I am not always clear why he has followed some historical lines further back than others. His choice is often rather personal but in each case the story he presents is full of interest. Together, these earlier studies set the stage for the attempt on the structure itself.

As a professional historian, Olby has been at pains to check and cross-check meticulously the details of the historical record. This by itself is no more than careful scholarshipit corresponds more to getting coordinates than to solving the structurebut Olbys professionalism has more depth than this. He develops the story from many points of view and he asks questions. Watson is perhaps inclined to regard an incorrect conclusion as a pure act of folly. Olby is more concerned to track down the roots of the mistake.

Sometimes the results of his investigations will come as a complete surprise even to those who were actively working in the field. Who would have suspected that Beighton, in Astburys laboratory, had obtained very good X-ray photos of the B form of DNA in 1951 and had not thought it worthwhile to publish them. At other times the facts were well known, at least in outline, but Olby has shed new light on them. In every case his reconstruction has been both imaginative and thoughtful. One follows with fascination the many aspects of the story of how the idea that genes were made mainly of protein was gradually replaced by our present ideas.

This, then, is the first full scholarly account of how the structure of DNA was discovered, set against its proper historical background. This does not mean it will be the last. The storyand what a good story it ishas too many ramifications for that. Some topics which Olby has touched on could well receive a longer treatment. If Watson had never come to Cambridge, who would have discovered the structure ? More important, how long would it have taken ? After all, the structure was there waiting to be discoveredWatson and I did not invent it. It seems to me unlikely that either of us would have done it separately, but Rosalind Franklin was getting pretty close. She was in fact only two steps away. She needed to realize that the two chains were anti-parallel and to discover the base-pairing. Wilkins, after Franklin left, could well have got there in his own good time. Whether Pauling would have made a second attempt (as we then feared) I am less certain. Olby demonstrates what was not clear to us at the time, that in the absence of our structure Pauling was not inclined to accept the more obvious criticisms of his own. Or, as Olby speculates, would the biochemists have hit on it in the end ? And, if so, what difference would it have made ?

Then there is the question of the motivation of the principal scientists involved, which often seems to contrast somewhat with the ostensible motives of the people providing them with money. Although Olby gives us much of the raw data on this topic it might deserve a more extended discussion. But that is the nature of history. What is I think certain is that no future historian of science in this area will be able to ignore the present volume, both for the thoroughness of Olbys investigation and for the good judgment he brings to the task.

FRANCIS CRICK

I cannot recall the word DNA ever being mentioned when I was a student at London University in the early fifties. How times have changed! Now this abbreviation for desoxyribonucleic acid is known far beyond the confines of university walls. J. D. Watson has provided us with an absorbing account of the discovery of its structure and others have added to the growing literature on the history of nucleic acid researches; but we still lack a broadly based study which will offer an overview of the whole intellectual and institutional movement in experimental biology which has yielded a physical and chemical account of the gene.

Next page