PROLOGUE: 19

OCTOBER 1962

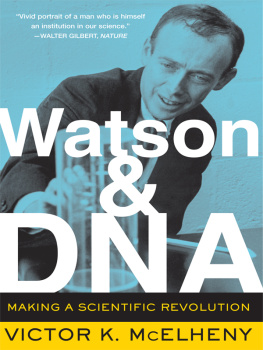

T he scientist spoke passionately about spring in Cambridge, England, in 1953, about the unattainable girls he called popsies, about tennis, and about the race to be first to discover the structure of the gene. It was the morning of 19 October 1962, and, sitting in the front row of a Harvard lecture hall, I left my dated note-page blank. The students in the Natural Sciences 5 class had expected to continue hearing about the revolution in biology from serene, white-haired George Wald, already one of the smoothest and best-known teachers in America. The subject of the course was biology, not a biology of accumulating facts about living creatures but a biology whose focus was protein and nucleic acid molecules carrying out the work of the cell under the direction of genesa biology concerned with the transfer of information from where it was stored to where it was used. Today, instead of Wald, a Martian string bean with wispy hair burst into the well of the lecture theater. A teaching assistant told us that 34-year-old James Watson had heard from Stockholm the previous day that hed won the Nobel Prize.

The students cheered as if for a home team. Then, nervously brushing back his wisps of hair, Watson thrust on them the special, frenzied romance he wanted his life to be. For an hour he recited, in a hysterical, flippant stage whisper, the adolescent tale that would become, a few years later, his sensational book The Double Helix. Whenever Watson was about to say something he thought funny, his eyes would open as wide as they could and he would suck in his breath through his teeth, and break into an anticipatory smile that was more like a grimace. His account was a torrent of emotions, false starts, and surprises.

There was no sense of a man at a stage of life different from that of his youthful, puzzled, amazed listeners. Maybe he had never grown up, or never had had the stuffing knocked out of him by his childhood peers. The self-editing inculcated in most of us was absent. It was a bewildering performance, oscillating between intense self-deprecation and burning arrogance.

The students had very likely never encountered a person as passionate about his subject as Jim Watson. He was incandescent, all right, while somehow not repellent. All of a sudden, the DNA revolution could be seen as a wild inside jokebizarre and romanticand he was letting us in on it.

To intelligent young people he stood for the promise of the new molecular biology: they could attack abundant problems at the most fundamental levels of life. In his world, the smart ones were the young, not the old gang. To be sure, I thought this wild man was in pain, and thought he needed protection, and a loving relationship with a woman, but he also was witty and racy, ready to be surprised and stimulated by new factsand he was serious about nature.

At the time he spoke to George Walds students, Watson was navigating in a storm of new ideas and experiments. Tensely cooperating and competing at the same time, scientists in labs at Harvard, Paris, and Cambridge, England, were racing to describe exactly how DNA drove the business of living cells: How did DNA duplicate itself, and how did it regulate the cells bewilderingly complicated second-by-second workings? The competing labs were focused on deciphering the code in which DNA language was written and in discovering how various types of a related substance, RNA, got the DNA message out to the cells protein factories. They also wanted to know how genes in cells that are specialized for particular tasks are shut off, as they must be; when a few of them do not, the result is lethal, an uncontrollably growing cancer cell.

As a young science reporter in the heady days after the Russians launched Sputnik in October 1957, I was predisposed to be excited by Jim Watson, even though he was living a story so rocky that it has become over the decades a kind of third rail of biography. He spoke to the students with such lighthearted and brutal frankness that one wondered if he mightnt be the most indiscreet scientist in the 300-year history of modern science. To the brash youths he was recruiting at Harvard and elsewhere to sweep aside the old biology, he offered no fatherly sympathy, but demanded that they be interestingdoing the next significant thing in science. Otherwise he would simply walk away. He mumbled in class, lecturing to the blackboard. He peppered his talks with seemingly irrelevant and sometimes malicious gossip about colleagues and competitors. Even when he talked with coworkers, he tended to look at his shoes. He frequently burst out in unpredictable anger. He once said, Nice is what you do when you have nothing else to offer! His countless acts of gen-erosity were equally unpredictable, however calculated they may have been.

Jim Watson wanted to be relevant, useful, helpful, influential, and, above all, never bored. He was an uncompromising rationalist, a believer in facts, and totally committed to the doctrine that to solve problems one must break them into manageable pieces. His style was to bring that days discoveries straight into the classroom, complete with anxiety and striving and gossip. This style was already attracting many of the best young people, including Harvard undergraduates, into the world of DNA science.

Aspiring young biologists fervently wanted Jims attention in spite of the fact that they felt anxiety leap the moment he entered the room. While writing the canonical opening advertisement for the field, Molecular Biology of the Gene, in 1965, Jim become an intellectual impresario at Harvard, building a laboratory that many regarded as one of the most exciting in the world. He was learning the lessons he would later use in his phenomenal 25-year rebuilding of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, on Long Island, and in getting the Human Genome Project rolling. Watson was teaching thousands of new biologists how to think about their field when it was exploding like a supernova.

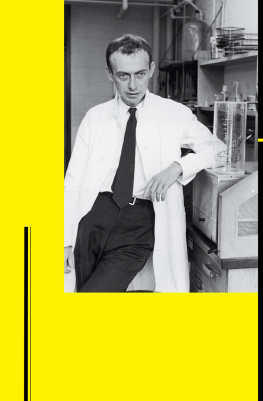

By the time of the Nobel announcement, Watson had largely left direct performance of scientific research. The day before, when journalists descended on his laboratory, the photographers demanded that the new Nobel Prize winner put on a white coat, something he never did. After resisting for a while, he complied, and gave a shy but triumphant smile.

The students listening that morning, though uncertain what Watson would say next, knew they were hearing the principal revolutionary of the brand-new world of DNA. With Francis Crick he had uncovered its double-helical structure, and like Crick he had striven to make additional significant discoveriesalthough he sensed that never again in his life would he make a discovery so important to science.

The purpose of George Walds class, Natural Sciences 5, was to introduce freshmen and sophomores to the racing advances taking place in biology. Only nine years had passed since the discovery that the genes were embodied in a double helix of DNA, but scientists had confirmed the Watson-Crick model and gone a long way in unraveling the basic steps for genetically controlling the machinery of the living cell. The discoveries were turning the operations of life from the ineffable to the knowable. Lifes workings were proving amenable to observation and experiment. In the approach often denounced as reductionist, biology now focused on the smallest and simplest components of life.

DNA was the subject for which the well-known South African biologist Sydney Brenner proposed the motto Think small, talk big. He added, Genes are, in fact, molecules, and they use molecular machinery to transform the messages they contain into other molecules. In 2002, Brenner shared in the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

Drawing heavily from physics and chemistry, these precise studies seemed likely to have vast relevance to increased understanding of the causes of cancer or hereditary diseases. Biology was beginning to seem less remote, and more practical, than the genetic-manipulation fantasies of a brave new world. Amid unceasing talk in the early 1960s about total destruction from nuclear bombs, here was a science of peace.