ALSO BY JAMES D. WATSON

The Molecular Biology of the Gene

(1965, 1970, 1976, 1987 [coauthor])

The Double Helix:

A Personal Account of the

Discovery of the Structure of DNA (1968)

Recombinant DNA (1983, 1993 [coauthor])

A Passion for DNA: Genes, Genomes, and Society (2000)

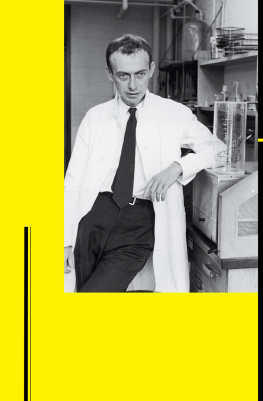

Jim Watson in Moscow at the International Biochemical Congress, 1961.

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2001 by J. D. Watson

Foreword copyright 2001 by Peter Pauling

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

www.aaknopf.com

Originally published in Great Britain in slightly different

form by Oxford University Press, London, 2001.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are

registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Watson, James D., 1928

Genes, girls, and Gamow: after The Double Helix/James D. Watson.1st ed.

p. cm.

A Borzoi book.

eISBN: 978-0-375-41443-5

1. Watson, James D., 1928 2. Molecular biologistsUnited StatesBiography.

I. Watson, James D., 1928 Double Helix. II. Title.

QH506.W399 2002

572.8092dc21 2001038543

[B]

v3.1

To Celia Gilbert

Contents

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.

Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

Foreword

It is reasonable for one to observe the universe about one and report what one sees. After all, there are countless reporters and correspondents who do just that for the media. Also, the first step in the scientific method is to observe and report ones observations.

Psychological interpretations, motivations, and intents are rather more dangerous.

As the chemist Harry Kroto clearly pointed out to me a year ago, Everything is subjective. In this book the subject is Jim Watson. There are many other players, real people, a good many of whom will be unhappy with the book (the Victims). Without them, however, there would be no book.

The information available to me indicates that the stimulus for this book is girls, particularly Christa Mayr. Being slow and egocentric, I did not realize that romantic Jim had such great problems about girls, although there was much evidence available. My problems were rather the opposite.

As a work of reference to what actually happened, this book is unreliable. There are many mistakes and errors of fact. Some of these are minor and refer to things that Jim did not observe directly.

I suggest that every coffee table and hairdresser have this book, the latter for the ladies to read under the hairdryer what is in many ways an entertaining book.

As unappointed leader of the Victims, I hope they will forgive or at least be lenient with both me and Jim.

PETER PAULING

Preface

The chase for the double-helical structure of DNA was an adventure story in the best sense. First, there was a pot of scientific gold to be foundpossibly very soon. Second, among the explorers who raced to find it, there was much bravado, unexpected lapses of reason, and painful acceptances of the fates not going well. The early 1950s were not times to be cautious but rather to run fast whenever a path opened upnuggets of gold might be lying exposed over the next hill. As one of the winners with a fortune much, much bigger than I ever dared hope for, I could not stop moving. There was more genetic loot to be located, and not joining in the further hunt would make me feel old. Out there was the genetic codethe Rosetta Stone of Lifethat would tell us the rules by which genetic information encoded within DNA molecules is translated into the language of proteins, the molecular workhorses of all living cells.

From the start, the best path towards the genetic code seemed in or near a still-mysterious molecule called ribonucleic acid, or RNA. Although quite distinct from DNA, it was built along the same lines and might also encode genetic information. In the spring of 1953, I had no idea what RNA looked like, and this book, in part, is the story of its pursuit. Conceivably mere inspection of RNAs three-dimensional form would tell us the genetic code and set us towards the molecular machinery that uses its rules to translate the language of DNA into the language of proteins.

In this search I again often had Francis Crick with me. But fates sometimes placed us thousands of miles apart, and many of my steps towards unraveling RNA were in the company of newer friends. For the most part, they had seen forests of seemingly impenetrable molecules before and knew approximately what clothes to wear and the tools needed to cut the thickets ahead. Quite different was the truly bizarre explorer, the Russian-born, George Gamow. Theoretical physicist extraordinaire, and a six-foot, six-inch giant to boot, Geo, as he ended his letters, defied conventional description with his penchant for tricks that masked a mind that always thought big. Together we were to form a club with a tie that he designed and called the RNA Tie Club. To its 20 members, Francis Crick sent his famous 1955 Adaptor Hypothesis that he never published elsewhere. Our club became part of the history of molecular biology.

For years I have wanted to write about how the RNA Tie Club came into existence, inserting Geos oft-illustrated, wacky letters into the intellectual climate that surrounded the spiritual upheaval among biologists after the discovery of the double helix. I could have restricted the story to scientific issues, but have placed it instead within the context of my own personal life, itself strongly influenced by the lives of my friends. The story starts when I was an unmarried 25-year-old and thought more about girls than genes. It is as much a tale of love as of ideas.

Like with The Double Helix, I try to capture the spirit of my youth and purposely do not make reflective judgment on where I was going right or wrong. Recapitulating the essence of times long ago, however, risks repeating long-held mismemories. Luckily and graciously put at my disposal were some 60 letters that I wrote to Christa Mayr Menzel between July 1953 and December 1955. In rereading them, I found an almost diary-like description of the people then entering my life as well as my scientific brainstorms of the moment. I also faithfully kept all the letters that I received from other close acquaintances of that period.

By purposely not judging my actions of those past days, I risk upsetting readers who want to see me as I am today, rather than as the inexperienced and more self-centered person I once was. There will be other readers, possibly not so harsh on my character either then or now, who nonetheless feel that many of the personal facts I write below are not worth being passed on to the future. Almost everyone goes awry in some aspect of their human lives, and what I describe may not be that unusual. But for better or worse, I and my friends were present at the birth of the DNA paradigmby any standard one of the great moments in the history of science, if not of the human species. In this way we were unique players in a momentous drama.