Linda B. Spurlock, Olaf H. Prufer,

and Thomas R. Pigott

Caves and culture : 10,000 years of Ohio history / edited by Linda B. Spurlock, Olaf H. Prufer, and Thomas R. Pigott.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-87338-865-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-87338-865-8(pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Indians of North AmericaOhioAntiquities. 2. CavesOhioHistory. 3. Excavations (Archaeology)Ohio. 4. OhioAntiquities. I. Spurlock, Linda B., 1949 II. Prufer, Olaf H. III. Pigott, Thomas R., 1948

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

This volume deals with cave and rockshelter excavations in Ohio based on the editors and contributors personal knowledge and experience. The only exception would be the brief introductory chapter by Robert N. Converse of the Ohio Archaeological Society. Converse has worked for nearly half a century with avocational archaeologists and professionals and has unrivaled knowledge of many more sites than he chose to put into his brief paper. He has a unique perspective based on his own experiences and the kind of information that is often unavailable to professionals because of the well-documented conflicts between them and the nonprofessional investigators.

Since readability is one of our major concerns, we have attempted to reduce parenthetical citations to a minimum. Many of the studies in this volume have been published in different formats since 1952, when little was known about Ohio cultural sequences in caves and rockshelters or, for that matter, open-air sites. Clearly, major revisions of earlier conclusions were in order. In addition to previously unpublished materials, these revisions comprise the major part of this volume. For purposes of reference, all citations are to previously published data and quasi-published studies (such as masters theses on file at Kent State University); we refrain from constantly referring the reader to chapters in this volume. Specifically, these previously reported sites include Stow Rockshelter, Peters Cave, Hendricks Cave, Chesser Cave, Wheelabout Cave, Stanhope Cave, Raven Rocks, Stricker Rocks, Gillie Rockshelter, Wise Rockshelter, White Rocks, and Krill Cave. In the chapter Additional Caves and Rockshelters, previously unpublished and minimally published sites include Laurel Run, Bob Evans Rockshelter, Tycoon Lake Shelter, Dolph Johnson Rockshelter, Rais Rockshelter, and Freeport.

A note is in order on measurements. It has recently been the fashion to take all measurements in the decimal system. Whether one likes it or not, in America, with some exceptions, measures are taken in miles, feet, inches, ounces, pounds, gallons, and cups. A recent but abating fashion has been to convert such measures to kilometers, centimeters, liters, kilograms, etc. There is nothing wrong with this except that it has not worked very efficiently. Not too long ago highway signs on freeways showed distances in both miles and kilometers. Now kilometers have largely disappeared. In practice, all meaningful measurements of any size in the United States are taken in terms of the traditional English system. A good example, in construction, is the two-by-four lumber board. The only time those of us in archaeology have consistently used millimeters and centimeters (for several decades) is for reporting the dimensions of artifacts. Archaeologists often dig in decimal units, yet topographic maps are in the English system. The result is that in publications older measurements are always painfully converted, in parentheses, to the decimal system. Texts become virtually unreadable. Since most of the older excavations and surveys deal with the English system, we have retained it in this volume. In rare cases, such as Nigel Brushs paper, we convert them backwards from the decimal to the English in order to render all geographic dimensions comparable to distances usually reported on maps and floorplans (but not in his plans and maps).

We are deeply indebted to many individuals who made available previously unknown data and observations on their researches. They include, in chronological order: David G. Mitten, Harvard University; Robert N. Converse, Ohio Archaeological Society; Douglas H. McKenzie, formerly of Cleveland State University; Charles Sofsky, formerly of the Warren Archaeological Society of Ohio; James L. Murphy, Ohio State University; Robert N. Williams, Mansfield, Ohio; Wayne Mortine, Newcomerstown, Ohio; Orrin C. Shane III, Minnesota Science Museum; George A. Reymond, director of Community and Economic Development of Tuscarawas County, Ohio; and Nigel Brush, Ashland University. We also wish to acknowledge the Department of Anthropology at Kent State University for facilitating this work, including the providing of financial support and clerical services. And we thank Evan B. Bailey, of Kent State University, for expert assistance with the graphics. The Prufer Archives can be accessed through the Department of Anthropology at Kent State University.

Introduction:

The Significance of Prehistoric Caves

ABSTRACT

The caves and shelters presented here are not particularly significant in their own right. They are important because they are part, through space and time, of broader settlement systems within a geographical context: Ohio.

Ever since the dawn of prehistory, caverns, caves, rockshelters, and overhangs have been used by prehistoric (and historic) peoples for various activities. For the purpose of systematics we will here provide a rough definition of these terms.

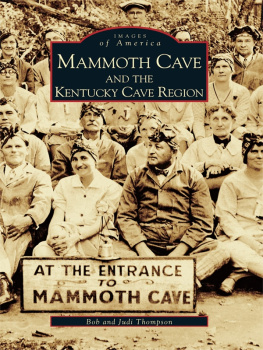

Caverns: This is a general term that denotes deep and extensive caves, usually in limestone deposits or sinkholes of similar geological associations, often a kilometer or more in extent. An example in North America would be the Mammoth Cave system and its subdivisions, such as Salts Cave in Kentucky (Lewis 1996). Examples of sinkhole caverns with apparent human occupations are known; and in Ohio they include Hendricks Cave (in this volume; and Pedde and Prufer 2001).

Caves: To some extent caverns and caves are interchangeable terms. They denote real, although not necessarily extensive, potential subterranean habitats in various rock formations. An example in Ohio would be Stanhope Cave (Spurlock and Prufer 2002).

Rockshelters and Overhangs: These terms essentially denote the same type of locale. They are open habitats protected by a variety of rocky ledges in various geological contexts. In Europe, specifically in France, such locations are known as abris.

In the Old World, as in the New World, such locations were extensively used by human beings since the Pleistocene. An Old World example would be Zhoukoudian in China, which yielded extensive human, faunal, and artifactual remains of the Lower Paleolithic. In the greater Eurasian area, especially in France and Germany, occupied caverns and caves, as well as rockshelters, are legion during the Middle and Upper Paleolithic. Occasionally such sites were also used in post-Paleolithic and even historic times. Speaking from personal experience, Prufer notes (1961) that habitation sites such as the Abri Schmidt in South Germany, a Late Aurignacian/Magdalenian rockshelter locality, are extremely common. By the same token, postStone Age occupations in protected shelters are also very common (Kunkel 1955).