Contents

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017, 2018

Text Andrew Cohen, Chris van Tulleken and Xand van Tulleken 2017

By arrangement with the BBC.

The BBC logo is a trademark of the British Broadcasting Corporation and is used under licence.

BBC logo BBC 1996

The authors assert their moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

Cover photograph Sciepro/Science Photo Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008256562

Ebook Edition May 2018 ISBN: 9780008256555

Version: 2018-05-02

Praise for Chris and Xand van Tulleken:

The van Tullekens are the pin-up doctors at the forefront of HIV research, medicine in war zones and the Ebola epidemic. Theyre so warm and likeable that theyve made roughly 20 TV shows between them in the past ten years. Proving that smart is indeed the new sexy, both van Tullekens are highly qualified doctors researching and treating infectious diseases, while their shows tend to involve hair-raising, death-defying or body-hacking challenges all carried off with inexhaustible good humour in the name of science. Indeed, their bucket list is as short as Chris stubble: to date theyve trekked to the North Pole, shoved spikes through their tongues and even won a BAFTA.

Evening Standard

To Kit and Anthony. For both the nature and the nurture. To Dinah. For the chromosomes and the hard yards youve put in with me and with Lyra. To Lyra and Julian From your Dads and your Uncle Dads. Xand and Chris van Tulleken

For my Mum and Dad, Barbara and the very much missed Geof Cohen. I couldnt have asked for more loving parents to help me grow, learn and survive. Andrew Cohen

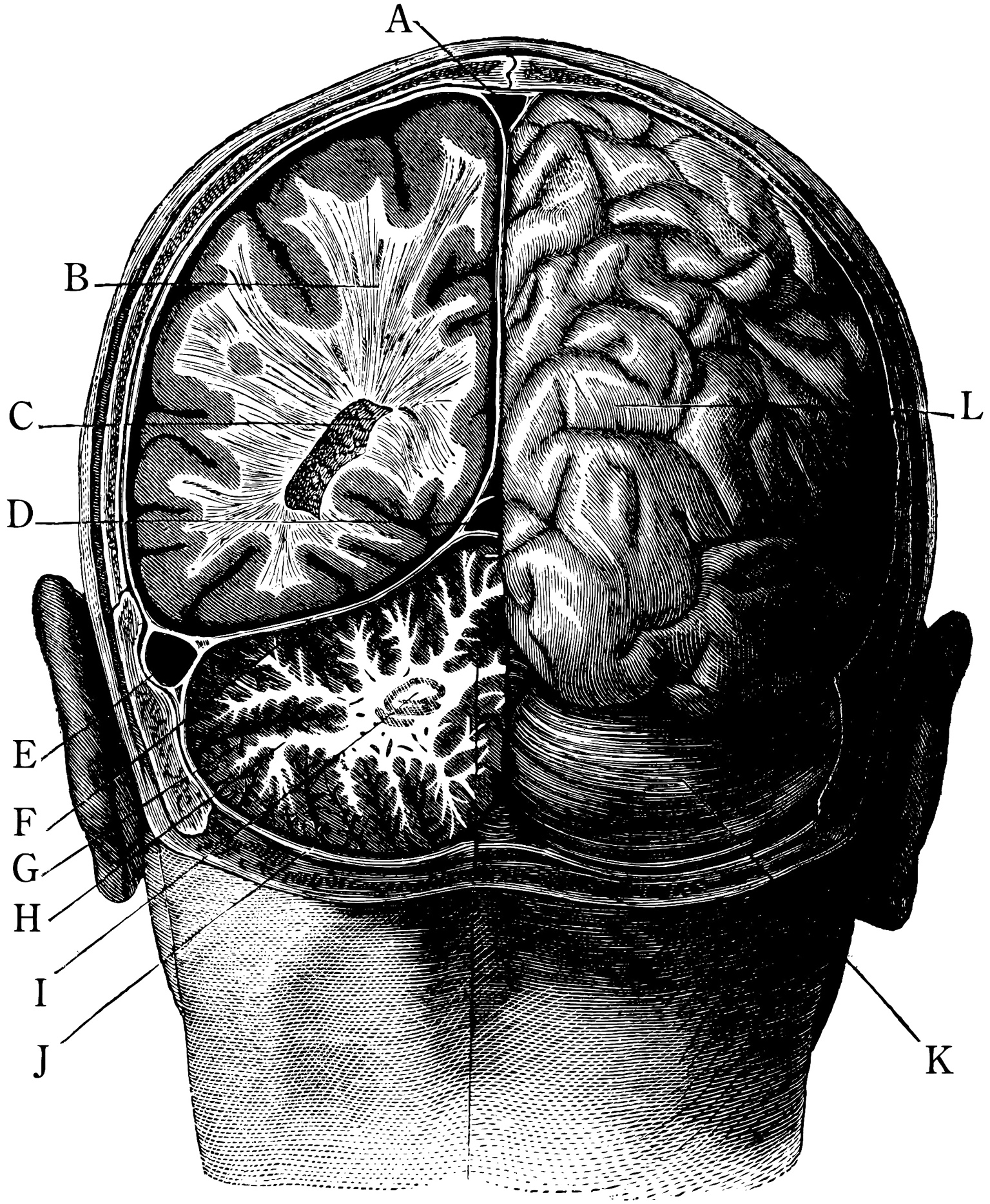

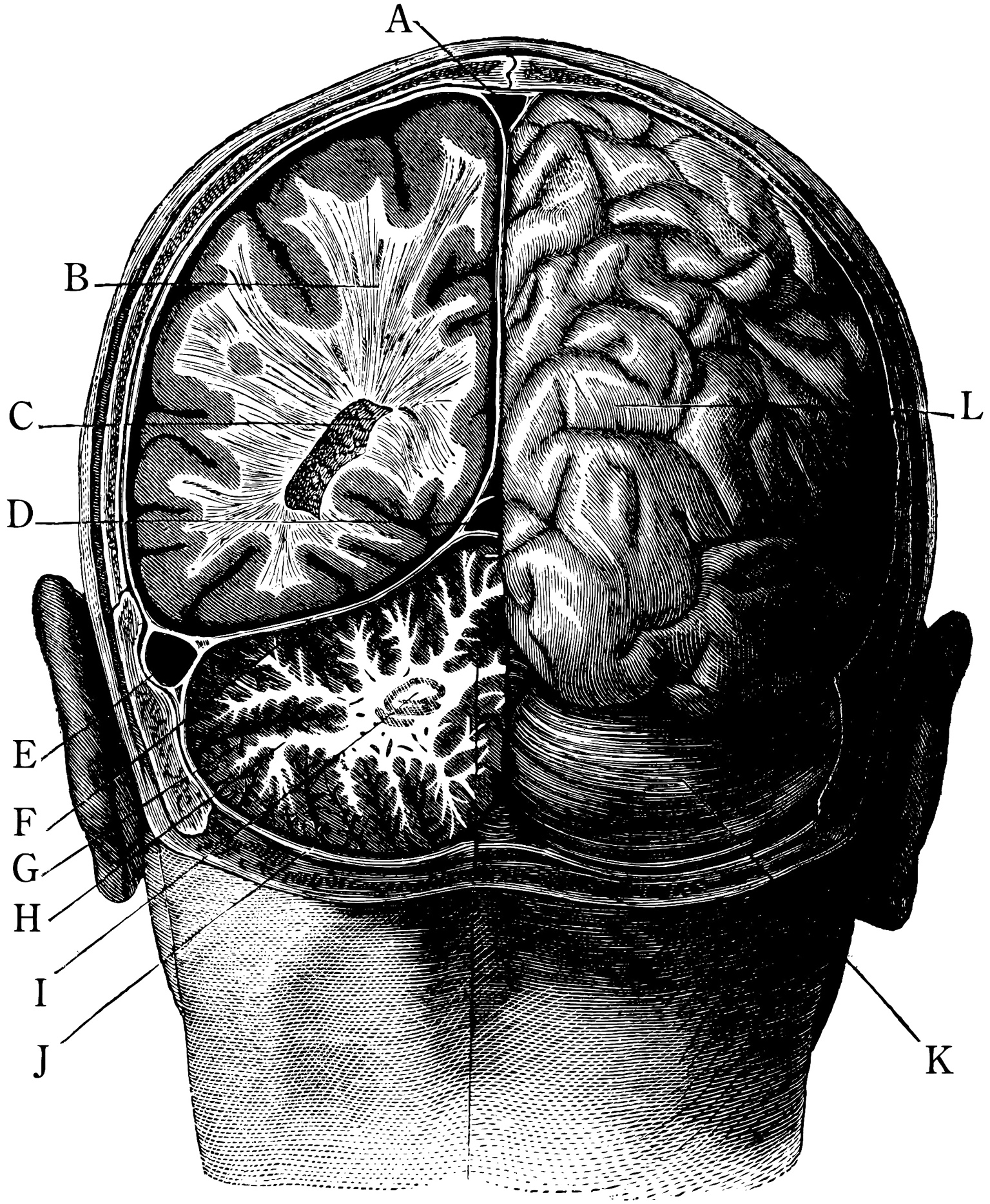

T he human body is in the business of keeping secrets. This was never more apparent to me than in the dissection room in my first year at medical school. The cohort of students was divided up into groups of six and we each had our own cadaver, the euphemism used for dead human body. Looking back, there was a great deal of secrecy about the whole endeavour: we were not allowed to know our bodies names or their life story (though peculiarly we were later allowed to attend their funeral if we wished). We were not allowed to take photographs. Only medical students and staff were allowed into the room, no backstage tours for curious friends. We were meant to be respectful, which generally we were, although the atmosphere was cheerful. We were not really exploring uncharted territory, after all there isnt much anatomy left to be discovered, at least not any that I was likely to find with my scalpel and forceps. We were more like a little gang of tourists trying to get to know a new town with the help of a guide book and tour guide, in the form of our instructor Professor Hall-Craggs. And yet we were uncovering secrets: we had views of our cadavers that few people had ever seen before. How many people in your lifetime will see you stark naked? Ten? Maybe twenty? OK, maybe more depending on your job and physique, but most of us keep most of our physical bodies concealed most of the time. For many of us it was our first experience with the intimacy with which we would later have to examine living bodies (I can really only speak for myself, not my classmates, but I had seen very few naked people at age 18). And how many people have seen the inside of your body, with its various anatomical irregularities? Probably none? Perhaps a surgeon? When cutting open a body, whether alive or dead, you get a sense of seeing into a place that no one has seen before, of being privy to a secret.

My group found that our cadavers false teeth had been left in and that they had a name engraved on them, I suppose to avoid mix-ups, which must be a concern when surrounded by older contemporaries later in life. It was a shock to think what else we didnt know about this previously anonymous man. Likewise finding his tattoos. Reminders of the secrets that were kept from us.

We got used to the smell (of chemicals, particularly formalin not rot or decay) and to the cold slippery texture of the bodies like kelp on a beach in winter. We also got used to the squeamishness that I think we all felt with the gristle and stomach contents and vast quantities of congealed fat. I remember Professor Hall-Craggs running his hands through his hair in exasperation at my continued failure to identify the various parts of the brachial plexus. He had been dissecting all morning and his hands were covered in bits of human, and so a large globule of human fat lodged in his hair, along with a decent amount of formalin and other small bits and pieces. I was amazed and impressed by his comfort with the material of these dead people who had so generously let us cut them up. I thought that my reluctance to really get stuck in and to leave the room at the end of each session with little parts of human in my hair probably accounted for much of my ignorance. I am sure I was right. You cant be squeamish and be a good student of the human body.

We got used to the strange sight of naked humans among clothed ones day after day. Medicine involves asking people to take their clothes off, to expose their bodies at different points. We do our best to preserve patients modesty but if you want to know whats going on with a persons body, you need to see it. We were taught two rules of thumb. If you want to examine someones abdomen (tummy), you had better expose them nipples to knees lest you miss the chest or thigh manifestations of some abdominal pathology. The other rule was if you dont put your finger in it youll put your foot in it. Meaning that we were not to shy away from rectal exams. It is frequently difficult, undignified and uncomfortable to reveal the secrets of any particular persons body. The early anatomy classes with our cadavers did a great deal to get us all used to the intimacy needed to examine and diagnose a person.

What I never got used to was the vast complexity of human anatomy. I passed my exams like everyone else. I even went on to teach anatomy at Cambridge for a term. But the sense of how hard it must have been for my predecessors to make the original anatomical discoveries stayed with me. I was doing what they, the early anatomists, had done: cutting up dead bodies. But those plastic models in the doctors office? It doesnt look like that at all. Its a confusing jumble of tubes and sinews. The question for me has stopped being how is the body put together? and is now why is it put together that way?

The early anatomists the important Italians, for example: Eustachius, Vesalius, Malpighi had to dissect, observe and catalogue with no knowledge of what the liver did or what a nerve was for. It is hard to imagine a contemporary equivalent. Perhaps mapping the outer reaches of the Solar System? Though the astrophysicists do not face either the smell of decomposition or illegality of obtaining scientific material that the anatomists did. They were in a very real sense uncovering secrets. Secrets that the church did not want them to know, that many older doctors did not want them to know and that the bodies themselves did not want them to know. No one in Renaissance Italy left their body to medical science.