DEDICATION I

To young gardeners, old gardeners, gardeners in their second or third childhoods, bow-legged gardeners, gardeners bald, gardeners hirsute, gardeners in kilts, Kent or the kinematograph trade, strabismic or teetotal gardeners, gardeners on their honeymoon, gardeners named Popjoy or Snafflethwaite, gardeners who believe that the earth is flat, scorbutic gardeners, gardeners whose forebears came over with William the Conqueror, gardeners with double-jointed thumbs or relatives in New Zealand, gardeners whose forebears came over with a day-trip from the Isle of Man, gardeners who only do it for their healths sake, and gardeners not specifically referred to above this book is dedicated with all possible respect and sympathy.

DEDICATION II

And the same applies to all who live by, for or on behalf of gardens, viz: florists apprentices, tulip-importers, the Royal Horticultural Society, wholesale seeds men of all sizes, trowel-testers, clothes-peg manufacturers, rookery-architects, buttonhole-cutters, hammock-salesmen, and even jobbing-gardeners with waterfall moustaches.

Two Dedications for the price of one! What more could the heart desire?

FOREWORD BY GEOFFREY BEARE

(TRUSTEE OF THE WILLIAM HEATH ROBINSON TRUST)

In the 1930s Heath Robinson was known as The Gadget King and he is still most widely remembered for his wonderful humorous drawings. But humorous art was only his third choice of career, and one that he turned to almost by accident. On leaving the Royal Academy Schools in 1895 his ambition was to become a landscape painter. He soon realised that such painting would not pay the bills and so he followed his two older brothers into book illustration. He rapidly established himself as a talented and original practitioner in his chosen field, and in 1903 felt sufficiently secure to marry. However, the following year a publisher who had commissioned a large quantity of drawings was declared bankrupt. The young Heath Robinson, who had just become the father of a baby girl, had quickly to find a new source of income. He turned to the high class weekly magazines such as The Sketch and The Tatler who paid well for large, highly finished humorous drawings, and within a short time was being acclaimed as a unique talent in the field of humorous art.

For a number of years, he combined his careers as illustrator and humorist with equal and growing success. One day he might be illustrating Kiplings A Song of the English or a Shakespeare play and the next would find him at work explaining the gentle art of catching things. He said of this time It was always a mental effort to adapt myself to these changes, but with the elasticity of my early days, it was not too difficult. During the First World War the market for luxurious illustrated books diminished, but demand for his humorous work increased, his gentle satires of the enemy proving popular both with the public at home and especially with the forces in the various theatres of war. This situation persisted after the war with very few commissions for illustration, but regular demands for his humorous drawings from popular magazines and for advertising.

In 1935 the Strand Magazine published an article titled At Home with Heath Robinson. This had a text by Kenneth R. G. Browne and ten pen and wash illustrations by Heath Robinson. The illustrations, which showed novel uses for unwanted items, were drawn under the working title Rejuvenated Junk. K. R. G. Browne, a fellow member of the Savage Club, was an ideal collaborator for Heath Robinson. He was the son of Gordon Browne who is still well known as an illustrator of books and magazines, and was the grandson of Hablot Knight Browne, who under his pen name of Phiz gained lasting fame as the illustrator of many Victorian novelists, including Charles Dickens, Charles Lever and Harrison Ainsworth. The article in The Strand Magazine marked the start of a partnership that was only brought to an untimely end by the death of Browne in 1940. During 1932 and 1933 Heath Robinson had drawn a series of cartoons for The Sketch entitled Flat Life, which depicted various gadgets designed to make the most of the limited space available in the contemporary flat. It was this series of drawings that provided K. R. G. Browne and W. Heath Robinson with the inspiration for their first full-length book together. It was called How to Live in a Flat , and as well as greatly extending the original ideas showing many ingenious ways of overcoming the problems caused by lack of space in flats and bungalows, also provided much fun at the expense of the more extreme designs in thirties furniture and architecture. The book was published by Hutchinson for Christmas 1936 and was well received.

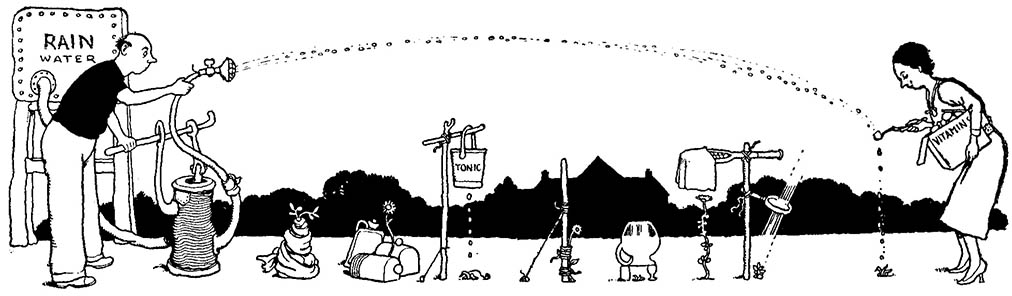

Over the next three years K. R. G. Browne and Heath Robinson successfully repeated the formula in a further three titles. Heath Robinson received much teasing from his family about the choice of subject for the second book, How to be a Perfect Husband , but looking back over his cartoons one finds that romance and courtship had been among his most frequently chosen subjects, from early Cupid cartoons to such pictures as The Coquette and Stolen Kisses which were reproduced in Absurdities in 1934. The next book in the series received a valuable preview when The Strand Magazine published an article called A Highly Complicated Science. The science referred to was that of gardening and the article by K. R. G. Browne was accompanied by nine of Heath Robinsons drawings all of which were subsequently used in How to Make a Garden Grow . Again, much of the subject matter for this book and the next, How to be a Motorist , was drawn from Heath Robinsons earlier cartoons. Among his earliest work for The Sketch was a series of drawings on the practicalities of gardening. This included a picture of root pruning showing the gardener tunnelling down to the roots of a plant to prune them. Although the earlier drawing is much more elaborate, the idea is the same as is presented on page 27 of How to Make a Garden Grow . Similarly the theme of motoring recurs frequently in his earlier cartoons.

But there is an important difference between the full-page cartoon for a newspaper or magazine, and the humorous book. The cartoon must be capable of making the reader laugh whatever his mood as he turns the page and so must achieve an instant impact with a strong idea and sound execution. The reader of a humorous book, on the other hand, will have picked it up in the expectation of being amused, and so here the author or artists problem is one of how to sustain the humour in an extended form, rather than to create a sudden effect with a single idea. In the How to ... books Heath Robinson found the opportunity to present the reader with a set of variations on a theme, allowing him to look at his subject from every angle and to explore each idea that presented itself. Thus the books allow us to see a different aspect of his humorous art; to see its depth, rather than just selected high points.