You know how to breathe. Right?

But do you suffer from headaches; shoulder, arm or back discomfort; upset digestion; or sleep problems? Or are you just tired all the time?

If so, you may not be breathing correctly.

We are becoming more sedentary. We think more and use our bodies less communicating all day with computer screens, becoming so absorbed that our shoulders tense, our breathing changes, we hold our breath too much and, by the end of the day, were exhausted.

Breathe, Stretch & Move includes methods which are designed to break this cycle. They will help you restore energy-efficient breathing and improve your energy levels, productivity and work pace. You will learn to run on natural not nervous energy, and your thought patterns will become calm but alert. You will reduce your stress levels naturally and without drugs.

Dinah Bradley and Tania Clifton-Smith the queens of calm are world experts on breathing pattern disorders. As practising physiotherapists they have an in-depth understanding of the physiological and musculoskeletal problems caused by bad breathing. Dinah is the author of Hyperventilation Syndrome. Tania is the author of Breathe to Succeed and they co-authored Breathing Works for Asthma.

contents

S tress is big business. A huge percentage of people who come to BREATHING WORKS clinics have done at least one course in workplace stress management. Yet they still complain that work stress is their main problem. Interestingly, they all complain of similar symptoms which include headaches; pain and tension in the neck, shoulders, chest and arms; upset digestion; and sleep problems. Bending over keyboards, talking for long periods on the phone, and working in artificially-lit, air-conditioned and often open-plan offices for eight to ten hours at a stretch is not good for us. With coffee machines and cafes around every corner, it is easy to become reliant on this abundantly available stimulant.

No one therapy will ever provide the whole answer when tackling job stress. There are often many rungs to be climbed on the ladder to health and happiness. We maintain that the first step in restoring health and stability at work, in both mind and body, is to pay attention to the breath. Many of our clients agree, remarking how simple and effective our methods are; indeed, many have described them as life-saving.

Fifty percent of recovery comes from learning about the basic physiological and mechanical processes of breathing. The other 50 percent comes from practising simple strategies to change bad habits into good ones. Many of the clients who have visited BREATHING WORKS have asked for more information on breathing and its relevance to their working lives. Many bosses have wanted to introduce our techniques to their staff as they say, there are plenty of policies on how to counteract workplace stress, but not much in the way of practical, simple, workable methods.

Our method is based on restoring the best breathing patterns by using the best breathing muscles, with easy moves and stretches to reduce mental and physical tension and stress. It is also about doing this from baseline calm, first and foremost using the knowledge of how and why we need to breathe well to be well. This includes learning the basics of balanced body chemistry (breathing properly) and the pay-offs through energy-efficient breathing (using the right muscles). While this book is primarily about breathing, which includes learning about breathings wonderful complexities, it is also about using enjoyable stretching and movement sequences to counter the perils of sedentary work whether this is standing, sitting at a computer, or driving for long hours.

We do not claim to have all the answers, but we have experienced enough success with BREATHING WORKS methods to believe that this first step in the management of stress and tension in the workplace is a legitimate one. Specific breathing-centred stretches and movements help prevent the problems mentioned above, and once you have reclaimed natural, relaxed breathing patterns you can look at other aspects of health such as nutrition and lifestyle.

www.breathingworks.com

A S YOU READ THIS CHAPTER, TAKE A SIP FROM A GLASS OF COOL WATER EACH TIME YOU TURN THE PAGE.

Here I was, 32, successful, doing all the right things (perfect diet, regular gym, beautiful relationship). But I was tired all the time, and I didnt think this was right. I loved my job but it was very fast-paced, even manic at times. My GP had tested everything all OK but sent me to a neurologist to be on the safe side because Id been a bit light-headed, which scared me. This guy picked it straight away. I was an upper chest, or reverse, breather par excellence!

LUCY, 32, JOURNALIST

I ts no news to most of us that feeling under pressure at work changes the way we behave, react and breathe. Sometimes this is invigorating and we achieve well, experience a healthy tiredness at the end of our working day, and enjoy a refreshing nights sleep. But for increasing numbers of people too much pressure across the working week is causing a great deal of harm. Deadlines bring on headaches. Traffic jams send blood pressure soaring. Too tired to cook means skipping meals or wolfing down unhealthy fast food. To combat our flagging energy levels we reach for stimulants. Too much coffee or alcohol and we start to shake. Sleep patterns are shot. We end up exhausted and prone to desk rage. Our breathing stays in overdrive.

SOLDIERS UNDER STRESS

Most of the original Western research on stress-related breathing problems came from studies of soldiers in active combat. As early as the American Civil War in the 1870s, stress and breathing disorders have been recorded and studied, as thousands suffered the ravages of dreadful food, sleep deprivation and mortal danger in combat. These disorders have been given a number of different titles, from Soldiers Heart (chest pain), Effort Syndrome (tired all the time) and Shell Shock (flashbacks) to the more recent Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Gulf War Syndrome.

As time went by, more and more was learned about the physiological consequences of changed breathing patterns on peoples body chemistry, and about their varied ability to cope under pressure. It also became clear that people in the workplace were affected by environmental stress. While the Industrial Revolution saw people working long hours in often noisy and confined spaces all year round, with no seasonal breaks (unlike traditional agrarian work) and in increasingly polluted urban environments , by the end of the twentieth century the electronic revolution had taken over as an equally potent source of workplace stress.

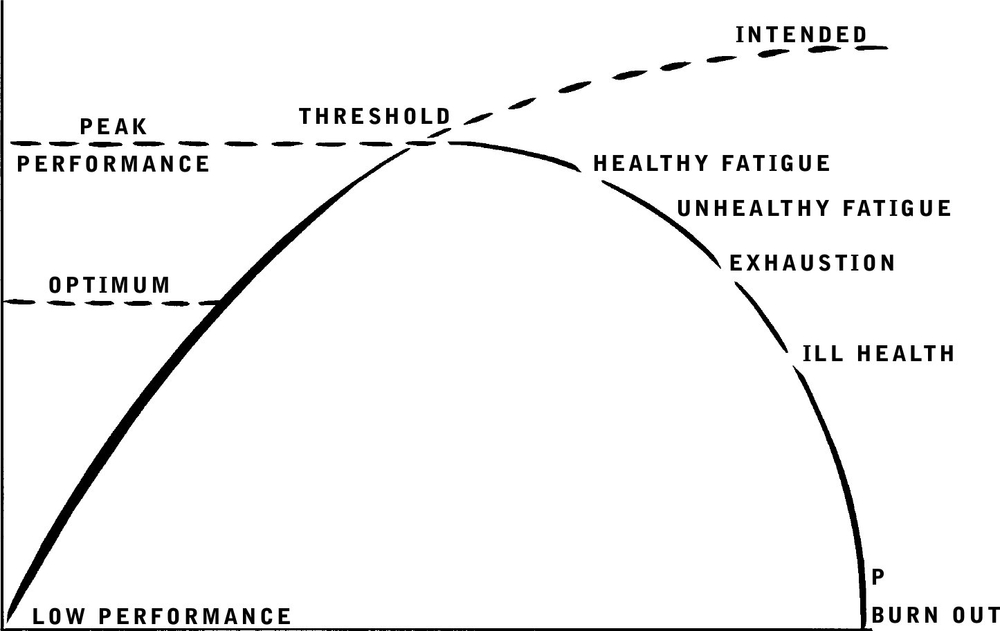

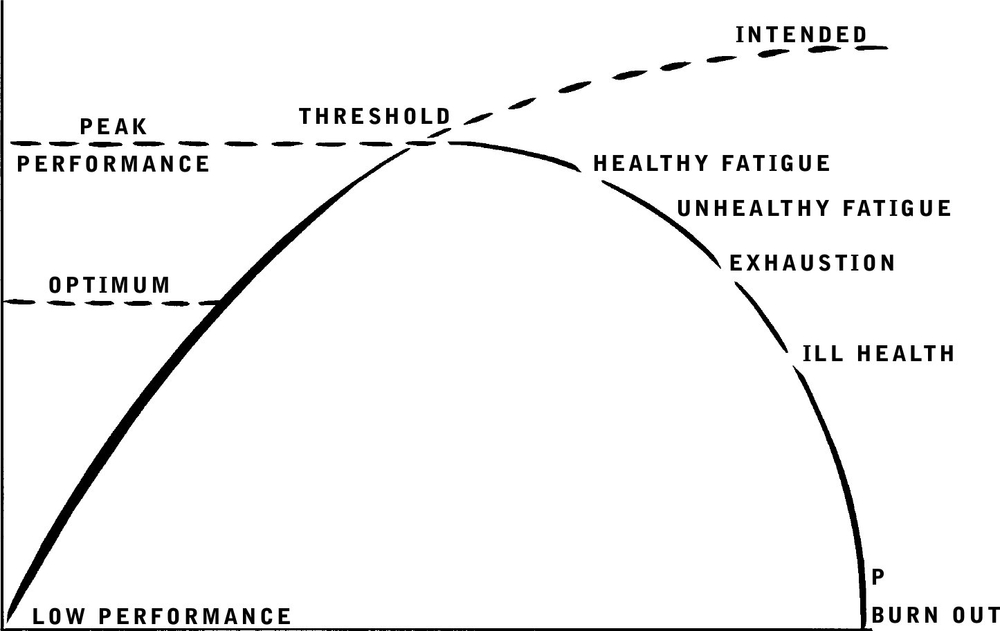

During the First World War a diagram called the human performance curve was used to illustrate what was happening to soldiers, both physically and emotionally. In the 1980s a modified version was developed by a London cardiologist, Dr Peter Nixon. He found that the majority of his patients with heart problems, women as well as men, had a history of prolonged physical or emotional stress preceding their angina or heart attacks. The message of the human performance curve is as relevant today as it ever was.

T HE HUMAN PERFORMANCE CURVE

( REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION FROM D R P ETER N IXON )

The curve shows the stages we go through when we are put under sustained mental or physical effort. The energy we have to summon to do certain tasks is guzzled up under pressure, and soaring adrenaline levels add anxiety to the mix. Normal fatigue is overtaken by exhaustion. If insufficient time is taken to recover, a feeling of being constantly under par is followed by ill health as we become run down and susceptible to colds and flu, chronic nasal congestion, anxiety, gastric problems, panic episodes, disturbed sleep and exhaustion, to name just a few of the conditions that are likely to strike. Whatever their level of intensity, these distress signals take their toll. Total burn out or P (breakdown the point at which recovery will not occur with normal rest) hammers down the final nail at the end of the downward slide. While healthy tiredness following extra effort may take two or three days to recover from, once burn out is reached, recovery time can be months or even years.