17. Trout In The Sky

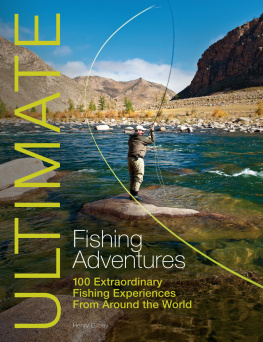

Having gone as far as we could, laterally, in Montana, we decided to try up.

IT WAS SIX A.M. and we were sitting in a restaurant at Silver Gate, Montana, 7000 feet high on the Red Lodge Pass. A moose and her calf were ambling down the main street. Our pack string was tied across the road at Elmer Larsons Switchback Lodge, and in the still morning air we could hear the horses restlessly stamping their feet, occasionally neighing. Moose and calf paid no attention, wandered on and disappeared behind a log cabin.

From across the road, Johnny Linderman signalled us that he was ready to go.

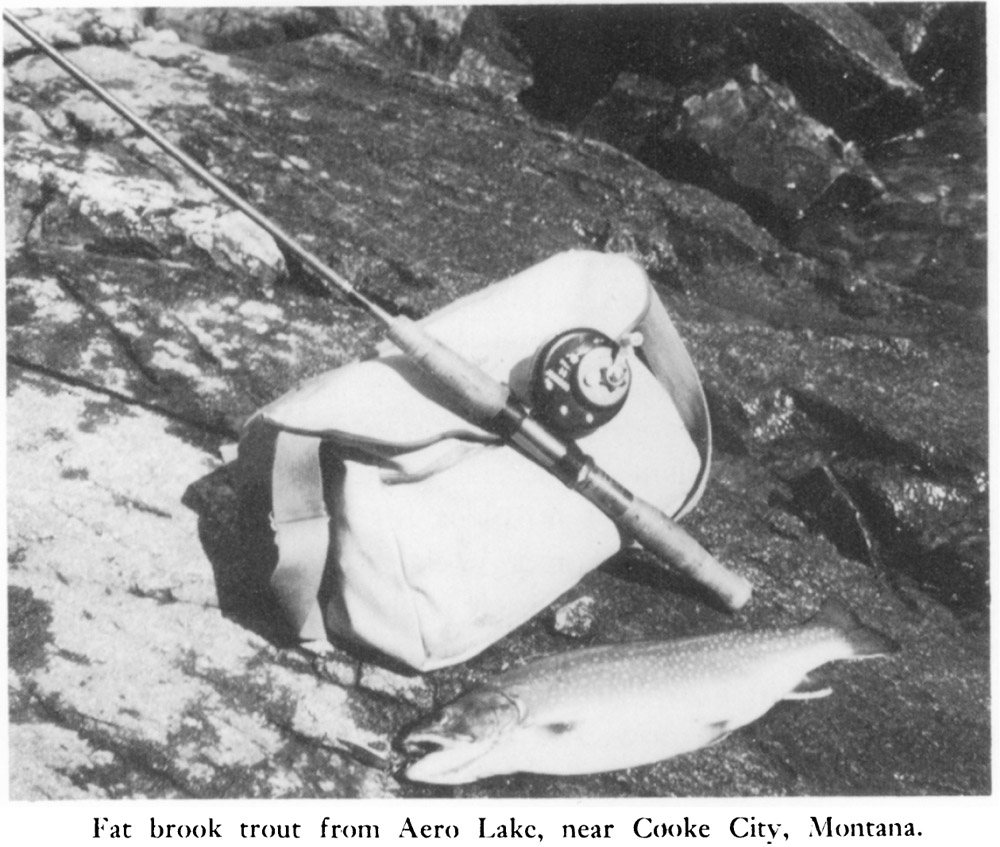

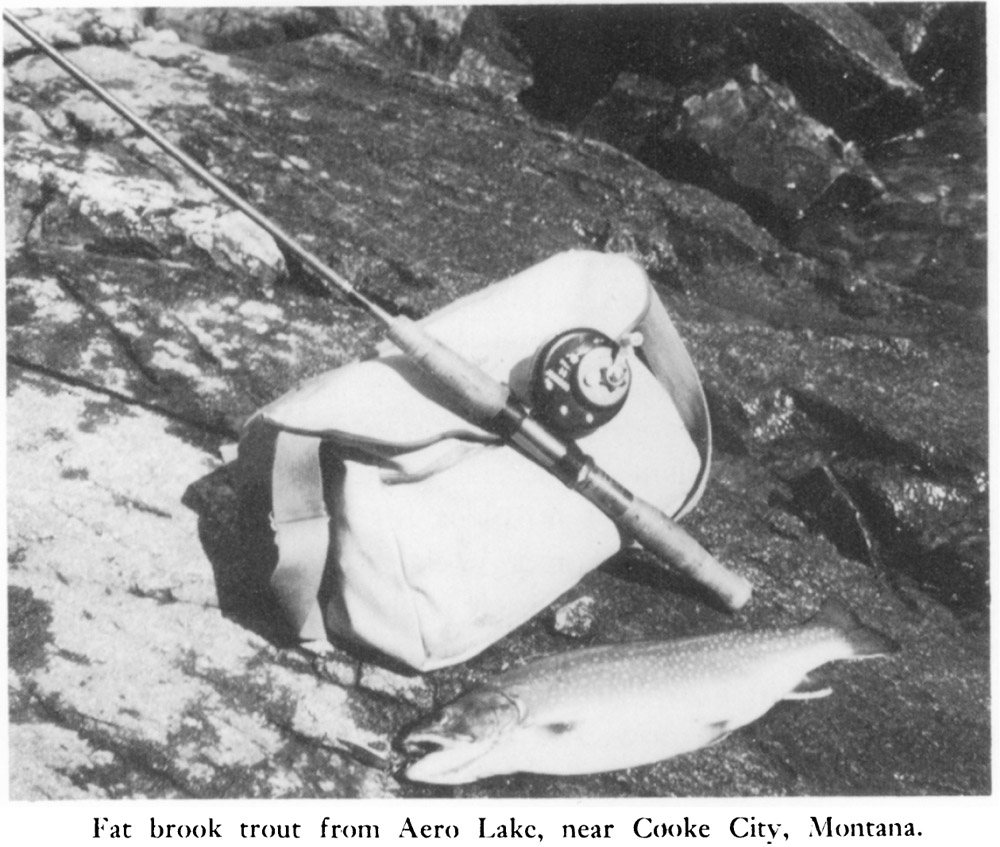

There were just the three outfitters, Elmer Larsen, Gene Wade, and Johnny Linderman, and five of us dudesGrace and Walt Weber, Bill Browning, and myself and wife. Walt was after pictures and sketches of alpine wildlife; Bill was after pictures, and I was just there for the fishing, to get some of those big brookies that were rumored to reside in well named Aero Lake.

Elmer and I have seen them in there up to five pounds, said Gene. The best looking fish Ive ever caught, fat and bright and full of pep.

Ive never been in to Aero Lake before, said Johnny. But I have been over it. I helped stock it from an airplane, back in 1937. Ive been as far as timberline on horseback, since, but never up those last 2000 feet.

But this string can make it, he added.

We looked at the horses with a mixture of dread and confidence. We knew that a Linderman, member of one of Americas best known cowboy families, would produce a good string of horses. What we didnt know was our own ability to stay on a good horse on such a ride as we were about to start.

It was a lung-busting climb. Aero Lake lies 11,500 feet high in the remote Upper Beartooth Range of Southern Montana. Twenty-five miles south as the crow flies, we could often spot Pilot and Index Peaks, famous landmarks for every traveller through this Montana-Wyoming border country. And about the same distance to our north the Grasshopper Glacier put a nip in the wind that could still be felt even at this distance. Close to Grasshopper was Granite Peak, the highest point in Montana, rising 12,850 feet into the sky.

The first part of the ride was through foothill country, if it can be called foothill when you are working up from 7000 to 8000 feet. But that was what the horses apparently considered it, and an old wagon road provided a good trail, so we ambled right along. But at 9000 feet the trail petered out into a narrow path through lodge pole pine. Almost at the same minute the temperature seemed to drop. We put on leather jackets over wool sweaters, donned gloves, and then really began to climb. We worked up through the timber on switchback trails, crossing sudden glades where there were deer and elk sign, and spooky clumps of pine where the horses shied at the scent of bear. Then suddenly we were out above the timber line and riding through shale and jagged rock that kept both horse and rider tense. It was practically straight up climbing, with the horses digging in with all fours and the riders hanging on the same way. We found out what saddle horns were for.

At last we came to what looked like a perpendicular wall, only a few chipped rocks showing where at some time a horse had gone up there, scrambling and plunging.

Get a good grip and hang on, said Elmer. This is pretty steep.

That was the understatement of the day. Even though the climb was short to the ledge we could see above us, it was the longest, hardest part of the trip. The grade was so steep that a horse could only make a couple of plunging steps before he had to stop to breathe and brace himself for the next lunge. Every movement sent sparks flying as iron clad hooves scraped the rock. Only the fact that I had heard about the law of gravity convinced me that we were not actually climbing on an outward incline.

But at last, one by one, our horses scrambled over the top, and onto a narrow ledge which ran along the side of the mountain. We dismounted and threw ourselves down to rest, as winded from that rocky ride as if we had climbed every step of the way on foot.

Above us rose a gigantic mass of rock, forming a jagged skyline.

The lake lies behind that, said Gene.

Were on foot from here, said John Linderman. Horses cant get over that divide.

He spoke with the heartfelt sadness of the cowboy who has no use for walking. And as we looked up to the divide, we shared his sadness. From here there was not even a hint of a path, only great, rounded boulders that must have been piled there by some ancient glacier. It might be duck soup to a mountain goat, but it was no place for a tenderfoot.

John will take the horses back down to pasture, said Elmer. The rest of us will each pack what we can over the divide.

Take a light load, instructed Gene. Dont forget, youre at 11,000 feet right now, and carrying will be tough.

Gene and Elmer each heaved a deflated rubber boat on their shoulders while the rest of us picked up loads from the welter of sleeping bags, air mattresses cooking gear and fishing tackle that Johnny was unloading from the pack horses.

Elmer looked at what we had chosen and grinned.

Take about half that much, he advised.

Then he and Gene started away, climbing slowly but steadily. We followed but within seconds were puffing and blowing, discarding part of our loads and finally collapsing on the boulders every two minutes to get our wind again. Elmer and Gene passed us on their way back for a second load before we had even reached the summit. They were beside us again with their second pack when we came over the top.

Right pretty, isnt it? said Elmer, as we stood spellbound.

Before us lay Aero Lake, a glittering gem of blue set in the midst of one of the bleakest Arctic scenes I have ever seen. The lake was almost circular, with two long arms running off into the distance and two little islands half way across. They had told us we would camp on the far island, and now we saw why. The mainland on which we stood was a solid mass of boulders, similar to the pass which we had just traversed. There was not a single square foot of land anywhere in which to sink a tent peg, just rocks, rocks, some as big as houses. Here and there the remains of a glacier running down to the shore afforded the easiest means of approach to the lake. All around us jagged peaks rose to poke at the sky, all bare and brown, without any vegetation at all, while lower down on our own level were only a few dwarfed bushes. It was as desolate as tundra country, bleak and forbidding, but lovely.

We stepped out onto the nearest snow field, following Elmers and Genes tracks toward the shore.

Suddenly Walt stopped and pointed down. I looked.

Hey, Elmer! I yelled. Whats this? The snow is bleeding!

Elmer came back to see what we meant.

Everywhere he and Gene had stepped, the snow glowed red in their foot prints.

Insects, he said. Thousands of tiny insects that live in the snow and only show up when you step where they are.

They certainly must be small, I said.

Look at those stunted cedars and willows, he replied. And the only animals youll see are the cony and a small ground squirrel. Everything is undersize up here.

Everything but the fish, he added. You dont need to worry about them being undersized

In the lake, which lay 25 feet below us, the water was so clear that you could have seen a penny on the bottom. The rocks shelved out quickly to a drop-off with here and there wide ledges running out just under the surface, ideal hiding spots for trout.

You go ahead and fish, said Elmer. Well set up camp on the island and then pick you up wherever you are along the shore.