Table of Contents

Guide

THIS PROJECT would not be possible without the dedication and remarkable industry of Denis Clift, the Naval Institutes vice president for planning and operations and president emeritus of the National Intelligence University. This former naval officer, who served in the administrations of eleven successive U.S. presidents and was once editor in chief of Proceedings magazine, bridged the gap between paper and electronics by single-handedly reviewing the massive body of the Naval Institutes intellectual content to find many of the treasures included in this anthology.

A great deal is also owed to Mary Ripley, Janis Jorgensen, Rebecca Smith, Judy Heise, Debbie Smith, Elaine Davy, and Heather Lancaster who devoted many hours and much talent to the digitization project that is at the heart of these anthologies.

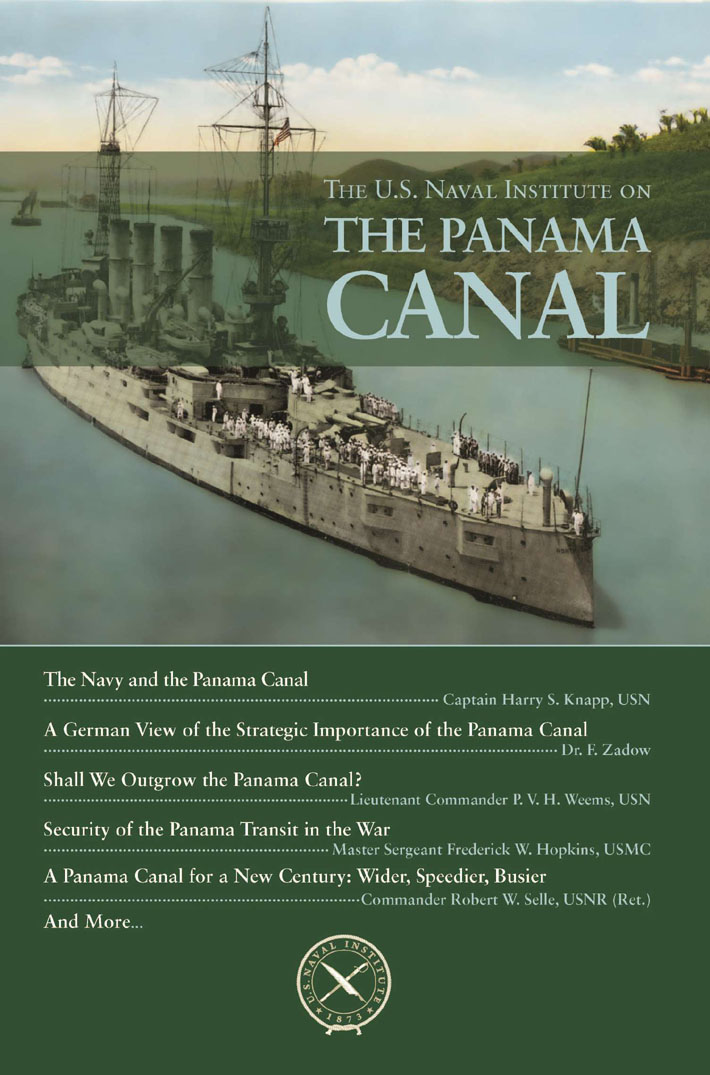

The Naval Institute Press is the book-publishing arm of the U.S. Naval Institute, a private, nonprofit, membership society for sea service professionals and others who share an interest in naval and maritime affairs. Established in 1873 at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, where its offices remain today, the Naval Institute has members worldwide.

Members of the Naval Institute support the education programs of the society and receive the influential monthly magazine Proceedings or the colorful bimonthly magazine Naval History and discounts on fine nautical prints and on ship and aircraft photos. They also have access to the transcripts of the Institutes Oral History Program and get discounted admission to any of the Institute-sponsored seminars offered around the country.

The Naval Institutes book-publishing program, begun in 1898 with basic guides to naval practices, has broadened its scope to include books of more general interest. Now the Naval Institute Press publishes about seventy titles each year, ranging from how-to books on boating and navigation to battle histories, biographies, ship and aircraft guides, and novels. Institute members receive significant discounts on the Press more than eight hundred books in print.

Full-time students are eligible for special half-price membership rates. Life memberships are also available.

For a free catalog describing Naval Institute Press books currently available, and for further information about joining the U.S. Naval Institute, please write to:

Member Services

U.S. NAVAL INSTITUTE

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402-5034

Telephone: (800) 233-8764

Fax: (410) 571-1703

Web address: www.usni.org

Captain George J. B. Fisher, USA

U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings

(September 1933): 131322

AS OUR SHIP PUSHES steadily across the Isthmus of Panama, we are constantly enveloped by an atmosphere of achievement. It makes itself felt as we rise through the locks of Miraflores and Pedro Miguel. In navigating the Gaillard Cut, there is the sense of sheer accomplishment. And the 85-foot drop at Gatun never fails to impart a thrill at what man hath wrought.

Here is tangible fulfillment. The dreams, the sweat, the blood of a fast-receding generation are all congealed into the masonry of the locks. The determination of our fathers is monumented for all time by breakwaters, dams, and now invisible excavations. The Stars and Stripes that float over it all bespeak creation just as proudly as they proclaim possession.

Yet we should never have had it except for the invincible will of a single Frenchman, Philippe Bunau-Varilla. Were it not for this resolute and single-purposed son of France, world traffic would today follow the Nicaraguan route from the Atlantic to the Pacific. It may yet, for that matter; but today Nicaragua remains a possibility while Panama is a reality. And behind all we have accomplished at Panama there hovers the shadow of Bunau-Varilla who so insistently pointed the way.

The dominant passion of Bunau-Varillas life was that the canal at Panama should be created. To this he dedicated himself under De Lesseps. But when in time the French effort collapsed, there emerged from the debris the lone, erect pillar of this one Frenchmans determination. While all others fled, he stood steadfast. The creation of the canal now became to him a spiritual issuenothing less than a vindication of French engineering genius. Nothing stopped this indefatigable engineer in the pursuit of his purpose. Discouragement, calumny, obstinacy, inertia, opposition, all melted in time before the intensity of his will. The impact of his personality on American thought came eventually to rival in his particular sphere that of Lafayette or De Grasse in theirs. The story of how he converted one antagonistic nation and disrupted another makes up a little-known romance of American history.

Bunau-Varilla first went to Panama in 1884, as a youth of twenty-five. A year before he had graduated from the Ecole des Ponts et Chausses, but already, at the cole polytechnique, he had fallen under the spell of the elder De Lesseps. So he sailed for America, imbued with the same patriotic fervor that carried so many young Frenchmen to their deaths under the banners of the Universal Interoceanic Canal Company. But the youthful Bunau-Varilla was not destined to fall a victim to yellow fever. Instead, he lived and thrived on the isthmus. Placed first in charge of the engineering works of Culebra and the Pacific slope, within six months he had command of two-thirds of the construction then under way.

We seldom give the French enough credit for what they accomplished at Panama. Not only did they pioneer; they had actually carried the project well on the road to completion when with the end in sight the battle was lostnot in Panama but in Paris. It was French politics coupled with indifferent financing that destroyed the confidence of the French peasant in his investment in Panama. The monarchists, anxious to discredit the republic, cried, See what scandalous waste democracy had led you into! The republicans in turn retorted, Watch how democracy can punish inefficiency in high places! When the smoke finally cleared away, Jean Homme had again hidden his hoard and the hundred-odd millions necessary to carry the canal to completion were not to be found. Confidence, on which the undertaking entirely depended, had vanished.

Finally, by 1893, even Bunau-Varilla was forced to admit that so far as France was concerned Panama was dead. Able resuscitator though he was, his every effort to reanimate the canal with French enthusiasm had failed. So he turned his face abroad. Not to the United States, however. The attempt to interest this country in the Panama plan came only as a final resort. Bunau-Varilla first took his ideas to Russia.

The Dual Entente between France and Russia had been signalized by Alexanders reception of the French fleet at Kronstadt in 1891. The alliance was cemented by a military concord between the general staffs of the two countries during the summer of 1892. Said Bunau-Varilla, Why not energize this new defensive alliance with a peaceful undertaking which will bind the two nations together in a profitable economic enterprise?

This proposition he laid before De Witte at St. Petersburg. The plan was for the Russian and French governments jointly to guarantee 3 per cent return on approximately $140,000,000 needed to complete the work of the French canal company. We know now that there was at least no engineering obstacle to the success of this scheme. The czars government was willing and promised Bunau-Varilla a favorable reception of such proposals from Paris. But here again the project was wrecked by French politics.

Next page