For Gerard Mancini, who manages an operation even more complex than the Panama CanalJBP

GROSSET & DUNLAP

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Text copyright 2014 by Janet B. Pascal. Illustrations copyright 2014 by Penguin Group (USA) LLC. All rights reserved. Published by Grosset & Dunlap, a division of Penguin Young Readers Group, 345 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014. GROSSET & DUNLAP is a trademark of Penguin Group (USA) LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-698-17185-5

Version_1

What Is the Panama Canal?

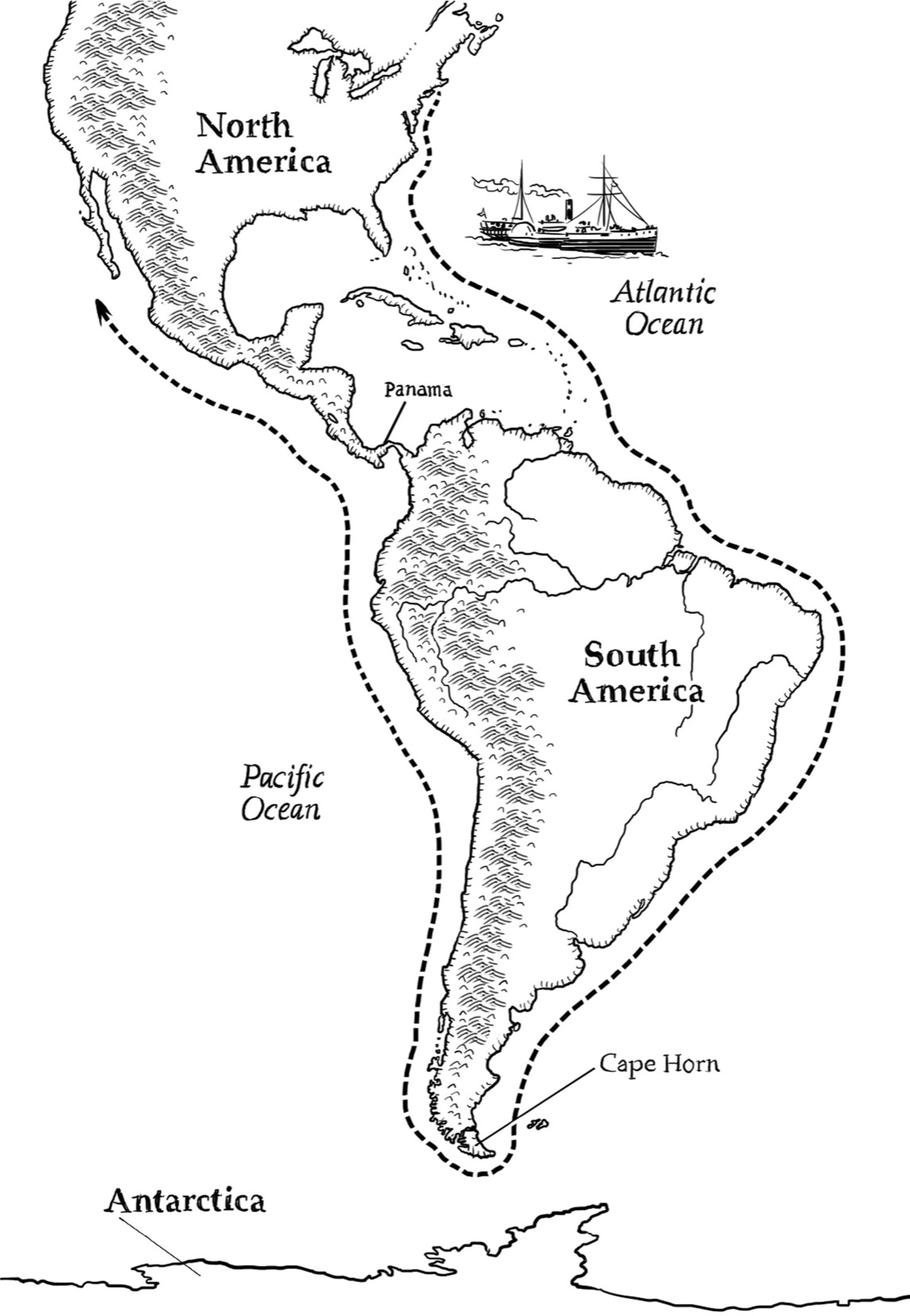

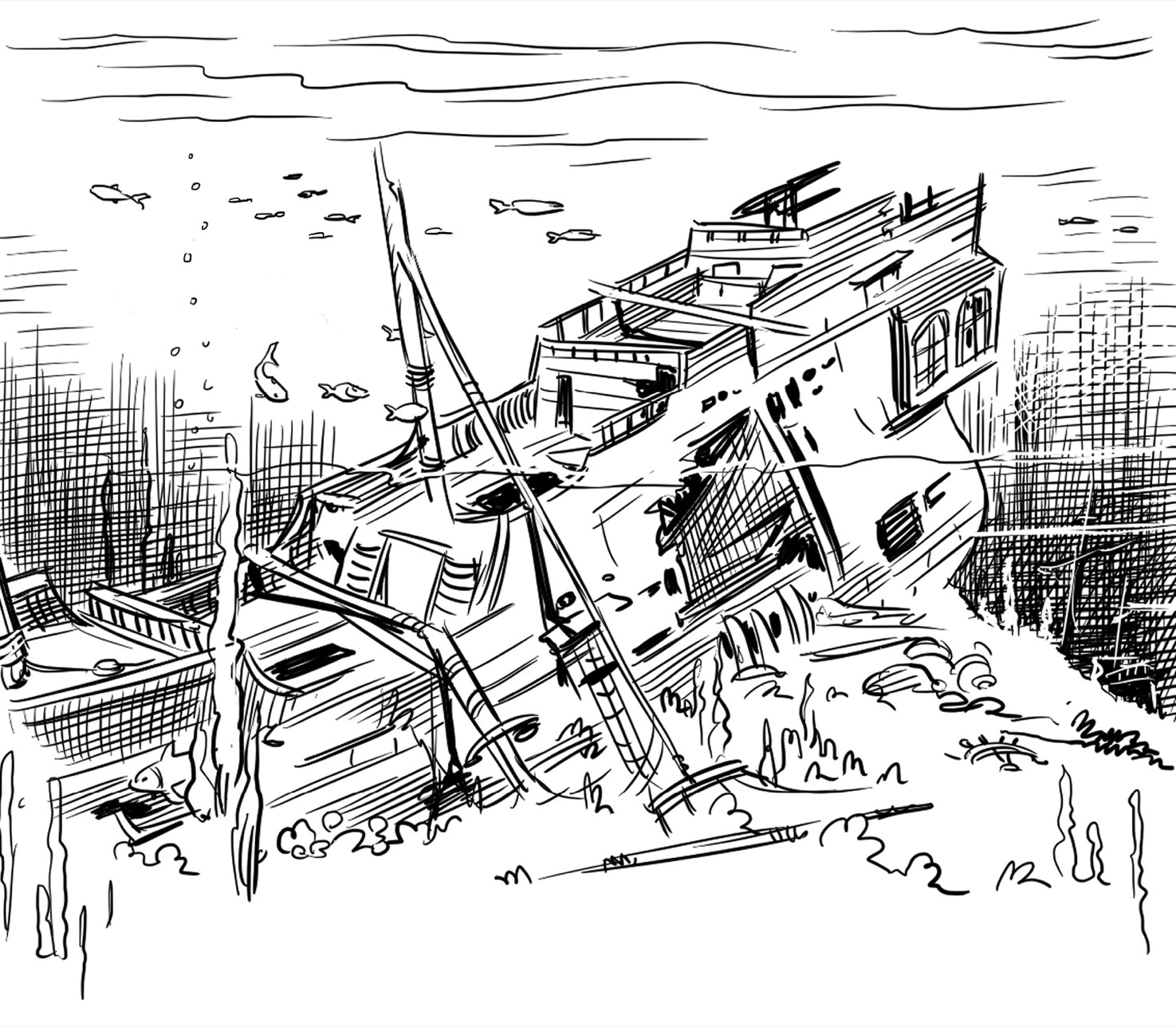

I would never... navigate... round that wretched place again. It is the kingdom of Satan, said a sailor in the nineteenth century. He was speaking of the trip around Cape Horn between South America and Antarctica. Rounding the Horn, as sailors call it, is one of the wildest, most dangerous trips a ship can make. For as many as two hundred days a year, gale-force winds blow there with gusts ranging from fifty to eighty miles per hour. The waves can reach ninety feet high or more.

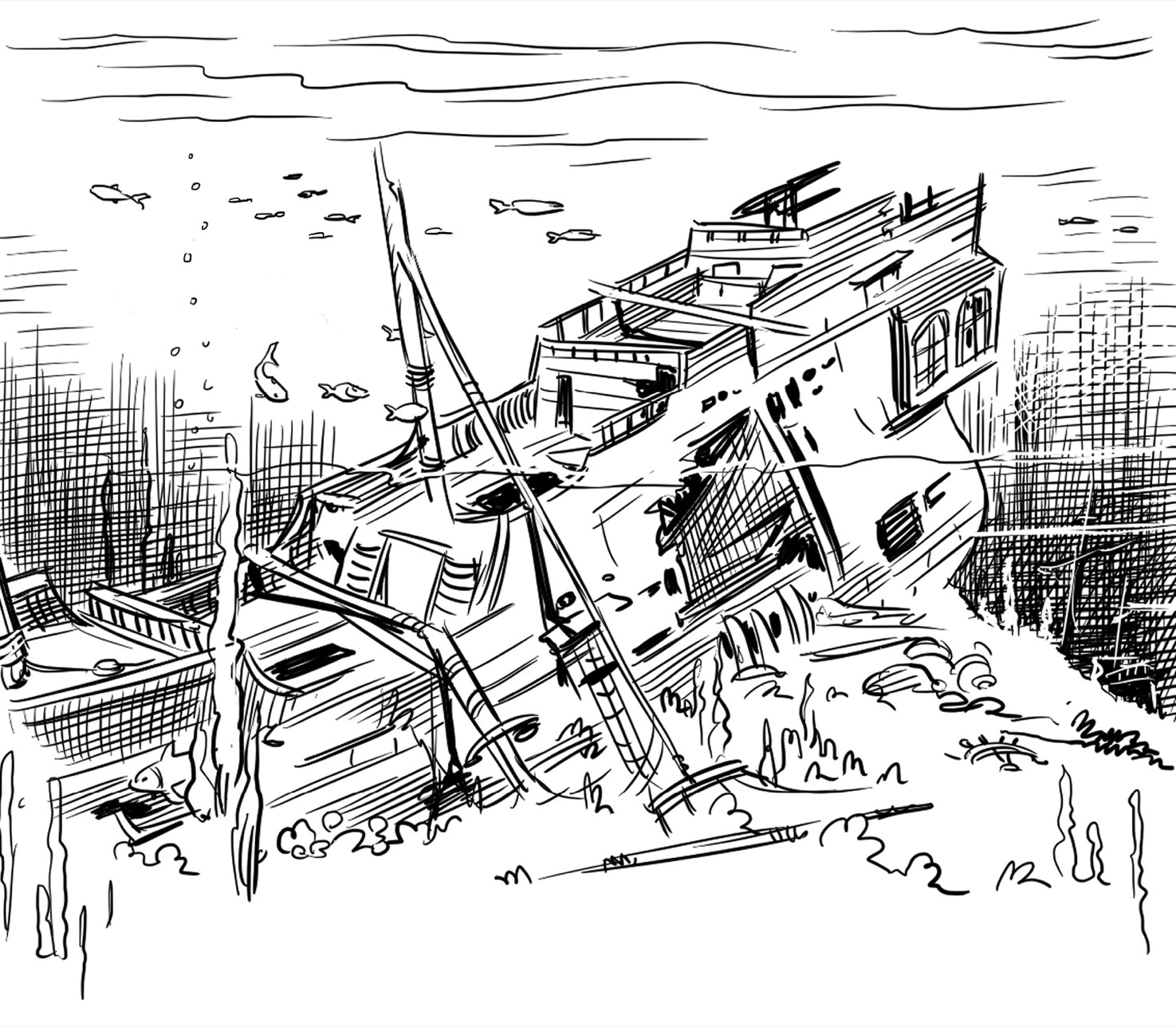

Yet for hundreds of years, if anyone wanted to sail west from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, they had no choice. They had to round the Horn. Surviving the trip became the sign of a truly brave seaman. After a sailor had managed to sail around the Horn three times, he could wear a silver earring, as a badge of honor. Many did not make it. No one knows for sure, but there may be one thousand shipwrecks lying under the water, and as many as fifteen thousand drowned sailors.

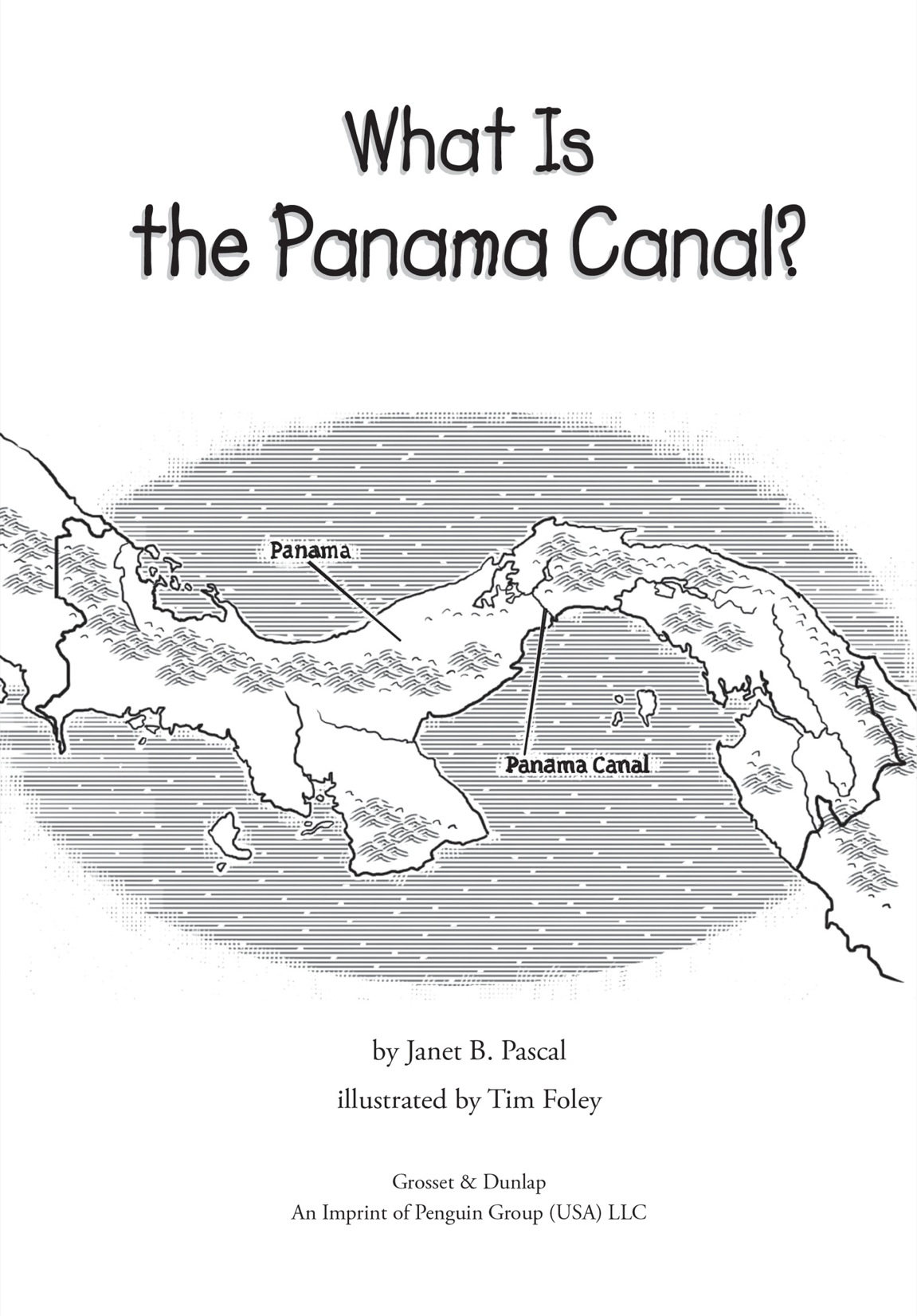

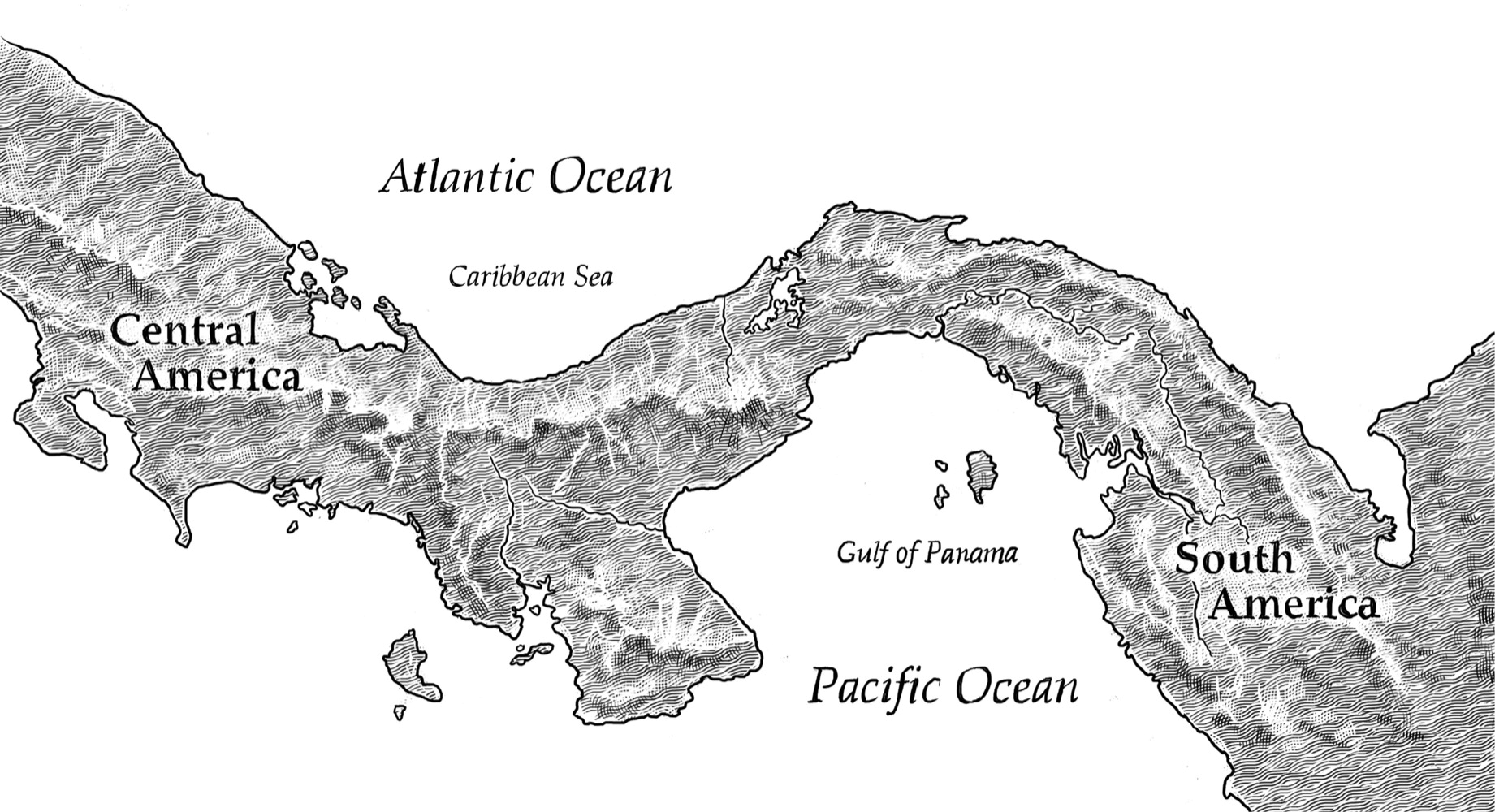

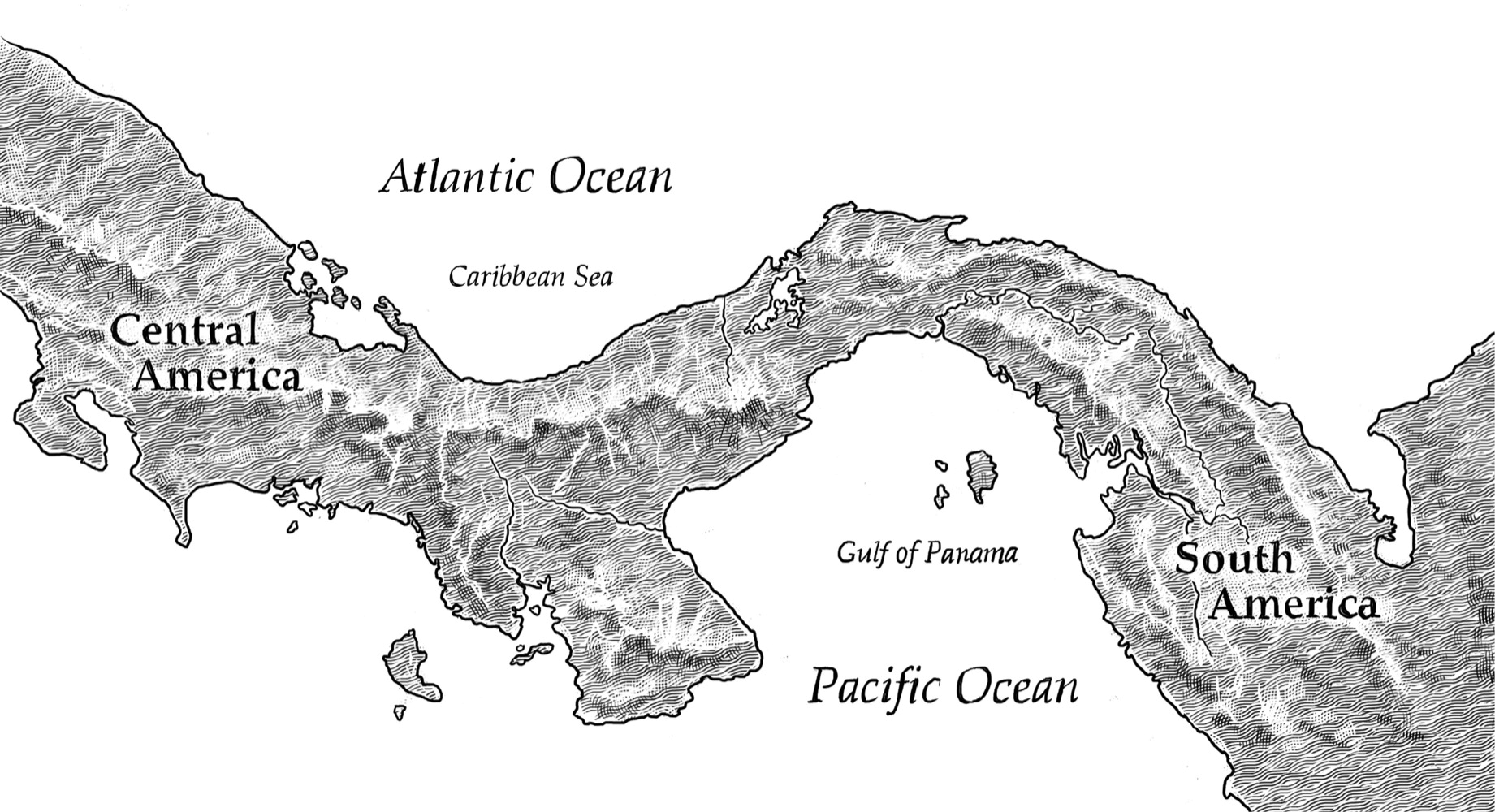

People dreamed of an easier way to sail from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. On maps, one place looked very promising. This was the Isthmus of Panama. An isthmus is a narrow strip connecting two pieces of land. The Isthmus of Panama joins Central America to South America. On one side is the Caribbean Sea, which runs into the Atlantic Ocean. On the other, the Gulf of Panama flows into the Pacific. At its narrowest, the isthmus is only thirty miles wide. The Atlantic and the Pacific looked so close together there! Surely some way could be found to cut across. Then ships would be able to sail right through Panama. The trip would become thousands of miles shorter, and no one would have to risk their lives sailing around Cape Horn.

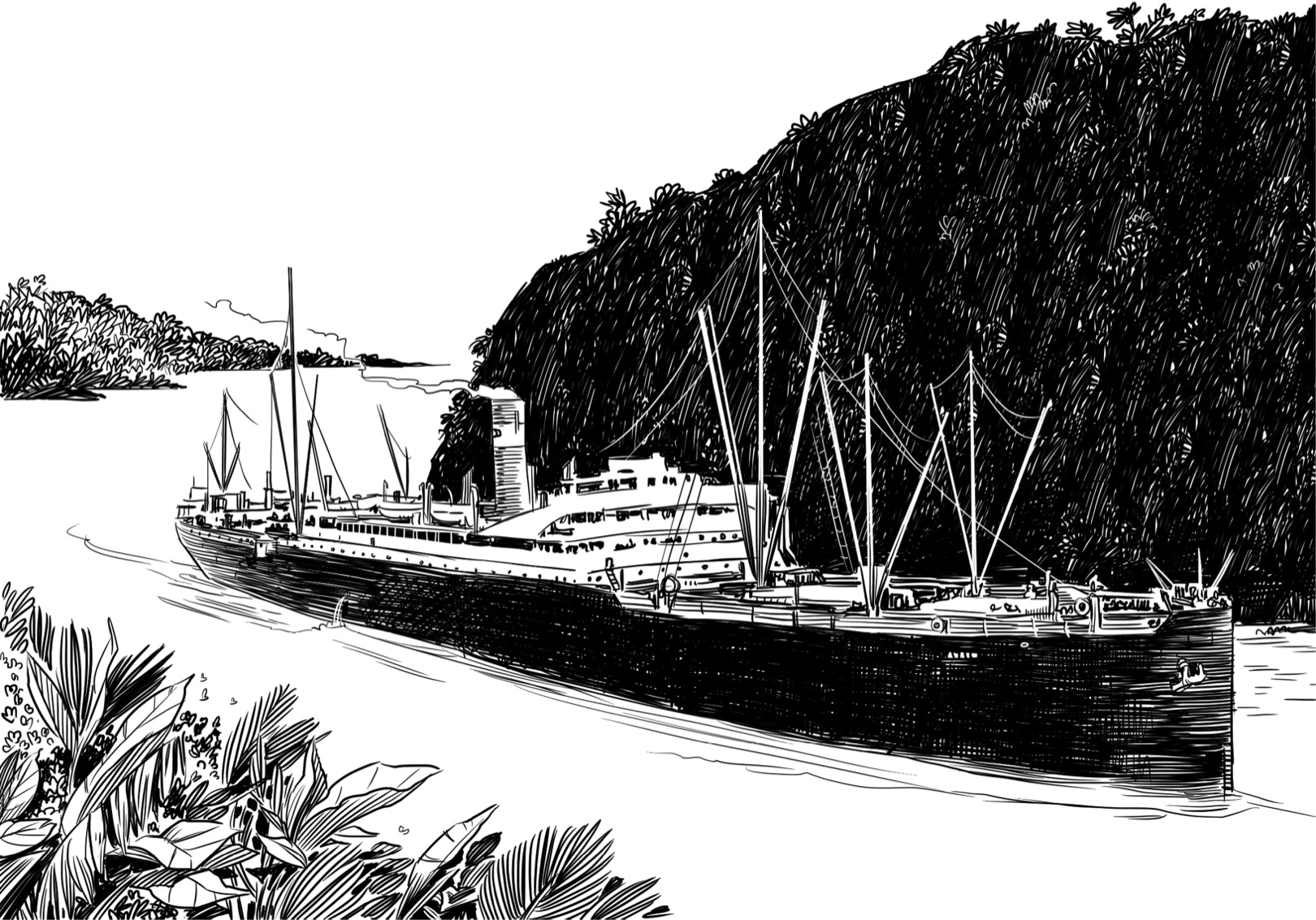

The reality was much more complicated than the dream. Panama was narrow, but it was rough and dangerous, with jungles, swamps, rivers, and high mountains in the way. It took years of work and failure before a passageway through was finally cut. Fortunes were won and lost. Thousands of people died. A revolution even had to be fought.

Finally the United States of America made the dream come true. On August 15, 1914, the first ship sailed through the Panama Canal from one ocean to the other. World travel would never be the same again.

CHAPTER 1

From the Atlantic to the Pacific

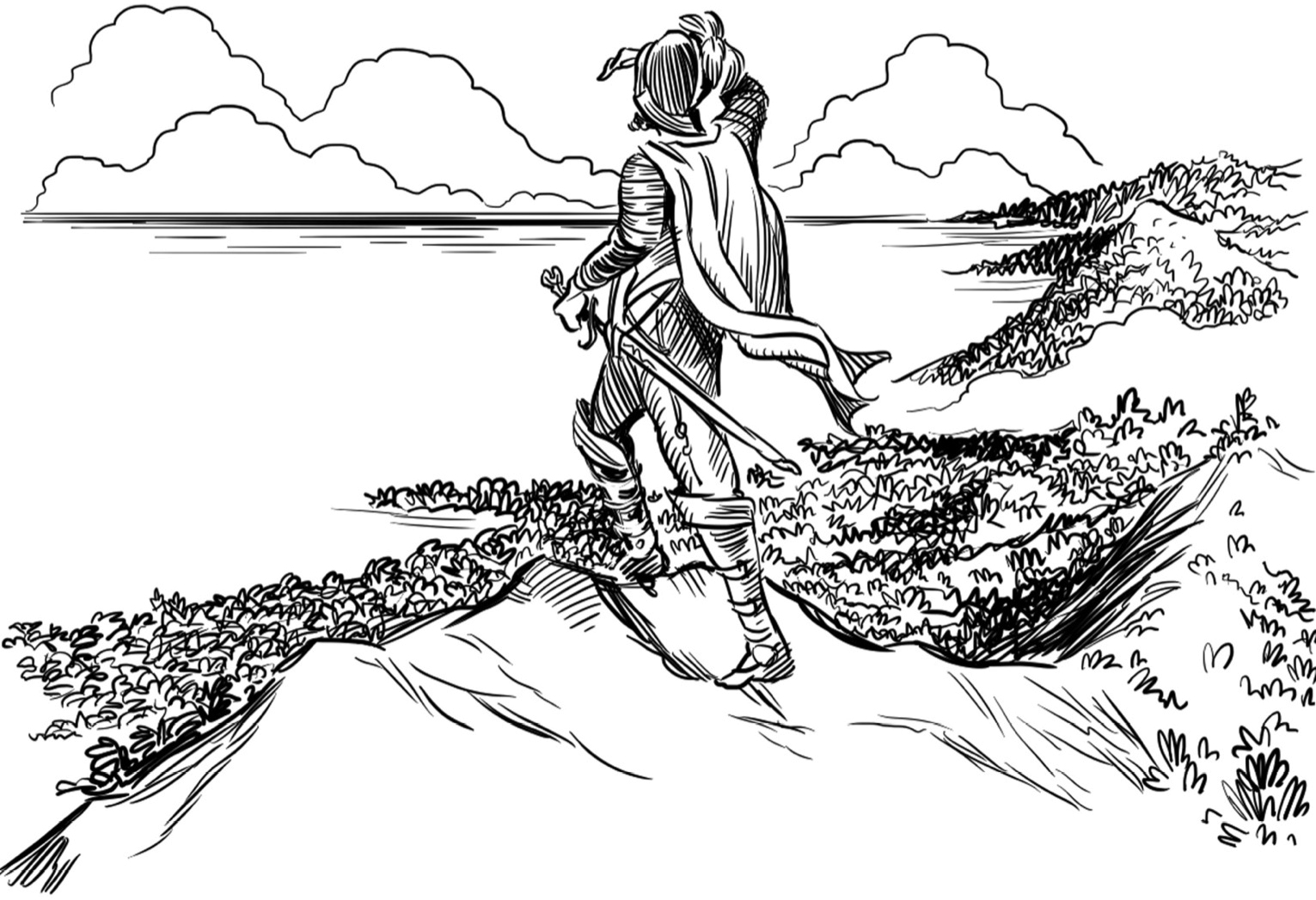

The first European to see the Pacific Ocean from the Americas was the Spanish explorer Vasco Nez de Balboa. In 1513, he was governor of a Spanish province in Panama. The local Indians told him about a place where, if he hiked only a short distance, he could see the ocean on the other side. So he took a small party of men and set out through the jungle and up the mountains. He made all his men stay behind him, to make sure that he would see the ocean first. On September 25, from the top of a mountain range, he spotted the Pacific Ocean in the distance.

A few years later, in 1534, King Charles I of Spain sent an expedition to find out if it would be possible to create a way through Panama by water. However, the expedition decided it was impossible. Instead the Spanish used two narrow roads cut through the isthmus. They ran through thick jungles and swamps. In places, travelers had to crawl on their hands and knees through deep, sticky mud. The Spanish used these roads to bring back gold and treasure taken from the Indians. Sometimes the mules carrying gold would slip in the mud and fall into pits filled with deadly snakes. No one dared to dive into these viper pits to rescue them. So they just abandoned the treasure. Legends say the gold is still there.

In 1848, gold was discovered in California. By 1849, eager gold seekers called forty-niners were racing to California, hoping to strike it rich. They came from all over the world. Miners all wanted to stake a claim to the gold before someone else beat them to it. So getting from the East Coast of America to the West Coast as fast as possible was vital.

For the first time in centuries, there was a lot of interest in the path across Panama. Traveling by land across North America to California in a covered wagon took months. Ships were faster. But the journey from New York to California by sea was 17,000 miles. Even on a fast ship, the trip would take three to five months. The journey from New York to Panama was only 2,000 miles. That trip took two weeks. The 3,500 miles from the other side of the isthmus to San Francisco took about three weeks more. And if you crossed Panama using the old Spanish roads, there were only forty-seven miles to go on foothow long could that take? Using a shortcut through Panama could cut the trip to less than half the time it took to round Cape Horn.