Table of Contents

FOUNDING EDITOR

Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.

BOARD

MEMBERS

Alan Brinkley, John Demos, Glenda Gilmore, Jill Lepore,

David Levering Lewis, Patricia Limerick, James M. McPherson, Louis Menand,

James Merrell, Garry Wills, Gordon Wood

AUTHORS

Richard D. Brown, James T. Campbell, Franois Furstenberg, Julie Greene,

Kristin Hoganson, Frederick Hoxie, Karl Jacoby, Stephen Kantrowitz,

Alex Keyssar, G. Calvin Mackenzie and Robert

Weisbrot, Joseph Trotter, Daniel Vickers,

Michael Willrich

ALSO BY JULIE GREENE

Pure and Simple Politics:

The American Federation of Labor and Political Activism, 1881-1917

Labor Histories:

Class, Politics, and the Working-Class Experience

(Coeditor, with Eric Arnesen and Bruce Laurie)

FOR JIM AND SOPHIE

my beloved

A WORKER READS HISTORY

Who built the seven gates of Thebes?

The books are filled with names of kings.

Was it the kings who hauled the craggy blocks of stone?

And Babylon, so many times destroyed.

Who built the city up each time? In which of Limas houses,

That city glittering with gold, lived those who built it?

In the evening when the Chinese wall was finished

Where did the masons go? Imperial Rome

Is full of arcs of triumph. Who reared them up? Over whom

Did the Caesars triumph? Byzantium lives in song.

Were all her dwellings palaces? And even in Atlantis of the legend

The night the sea rushed in,

The drowning men still bellowed for their slaves.

Young Alexander conquered India.

He alone?

Caesar beat the Gauls.

Was there not even a cook in his army?

Philip of Spain wept as his fleet

Was sunk and destroyed. Were there no other tears?

Frederick the Great triumphed in the Seven Years War. Who

Triumphed with him?

Each page a victory.

At whose expense the victory ball?

Every ten years a great man,

Who pays the piper?

So many particulars.

So many questions.

BERTOLT BRECHT

INTRODUCTION

IN 1915, as Americans planned a grand worlds fair to celebrate the completion of the Panama Canal, California artist Perham Nahl created a lithograph he called The Thirteenth Labor of Hercules. In Greek mythology Hercules, the brave and strong son of Zeus, had to complete twelve arduous labors, including such unimaginable tasks as diverting rivers and carrying the earth on his shoulders. With the construction of the canal, Nahl suggested, Herculessymbolizing the United Stateshad finally and triumphantly completed his thirteenth labor.

Nahl depicted Hercules thrusting apart a mountain range, his back pushing against one side while his arm forces away the far side. His mighty labor allows a gentle stream of water to pass by at his feet. A small boat traverses the distance toward a mythic city on a hill. Hercules shows no sweat; his muscles are poised but not straining. He is turned away from us, his head lowered as if in benediction. We do not see his face. What we see is his masculine body conquering Mother Earth and making possible a great wonder of the world. By connecting the canal construction to Greek mythology, Nahls image brilliantly invoked the spirit of the canal while honoring the nation that built it and linking it to the greatest ideals of Western civilization. America now stood as a Hercules, achieving a godlike task through a bloodless conquest over nature.

The lithograph of Hercules helped draw people in 1915 to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, where more than eighteen million visitors marveled at the wonders of American industrialismincluding many of the technologies that helped make the Panama Canal possible. The fair emphasized the links between industrialism and Americas emergence as a leading world power. Nothing exemplified those links more clearly than the recently completed canal, hailed by observers around the world as a miracle of engineering and industrial technology. The fair, like Nahls lithograph, celebrated the canal while diminishing the role of the tens of thousands of men and women required to build it.

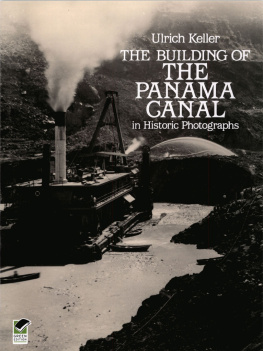

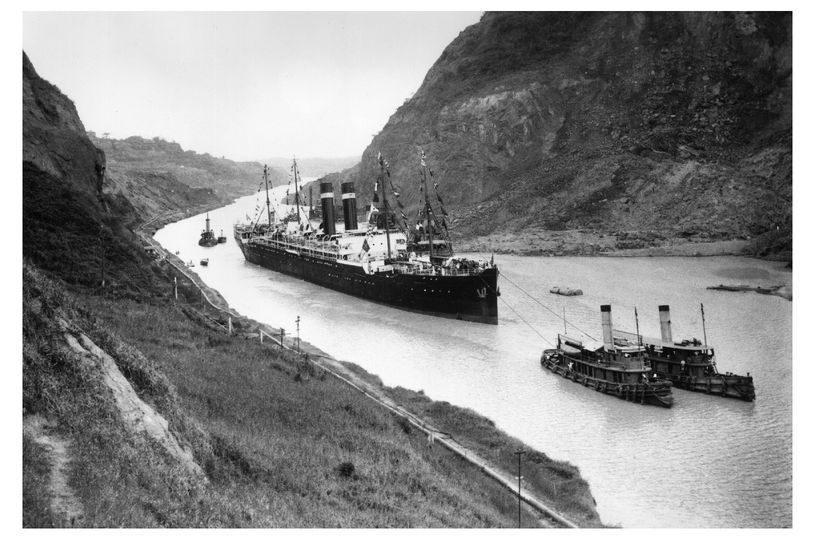

These are the aspects most of us remember about the canalits a tale enshrined in popular memory and innumerable histories and novels. Most narratives begin by pointing out that the dream of a canal was centuries old, but only the Americans achieved it. In 1880 the French, under the leadership of Ferdinand de Lesseps (who had previously constructed the Suez Canal to great acclaim), began trying to build a canal across the Isthmus of Panama. Frances effort ended in failure in 1889 due to mismanagement, devastating disease, financial problems, and engineering mistakes. In 1904 the United States took over the job, with the ingenious President Theodore Roosevelt leading the way. Breakthroughs in medicine, technology, and science and wise engineering decisions, according to traditional accounts of the project, allowed the United States to succeed where France had failed. Engineers who had helped build the transcontinental railroad and diverted rivers in the United States applied their experience and determination amid the chaos (and debilitating humidity and rain showers) of the Isthmus of Panama. The engineers brilliantly figured out how to dig through the Continental Divide, how to dispose of all that dirt, and how to handle the mudslides. Most important of all, they decided they must rely on locks to raise and lower the ships, rather than attempting to build the canal at sea level. It was built ahead of schedule and under budget, costing only $352 million. The Panama Canal opened to tremendous celebration in August 1914, and it marked the emergence of the United States as a world leader at the very moment when World War I broke out and split the nations of Europe apart.

It was a difficult, challenging taskin a word, Herculeanbut thanks to a few individuals of genius, it worked. And through it all the will and spirit of Americans never wavered. Indeed, central to this common narrative is the notion that the canal project demonstrated the superior character of the American people. In 2005 the historian David McCullough, author of