Copyright 2018 William D. LaRue

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. All photos inside this book, except where noted, are from the personal collection of Kenneth P. Puckett.

Published by Chestnut Heights Publishing

Print ISBN 978-0-692-08611-7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018938530

Contact Kenneth P. Puckett at panamacanalpilot.com

Contact William D. LaRue at williamlarue.com

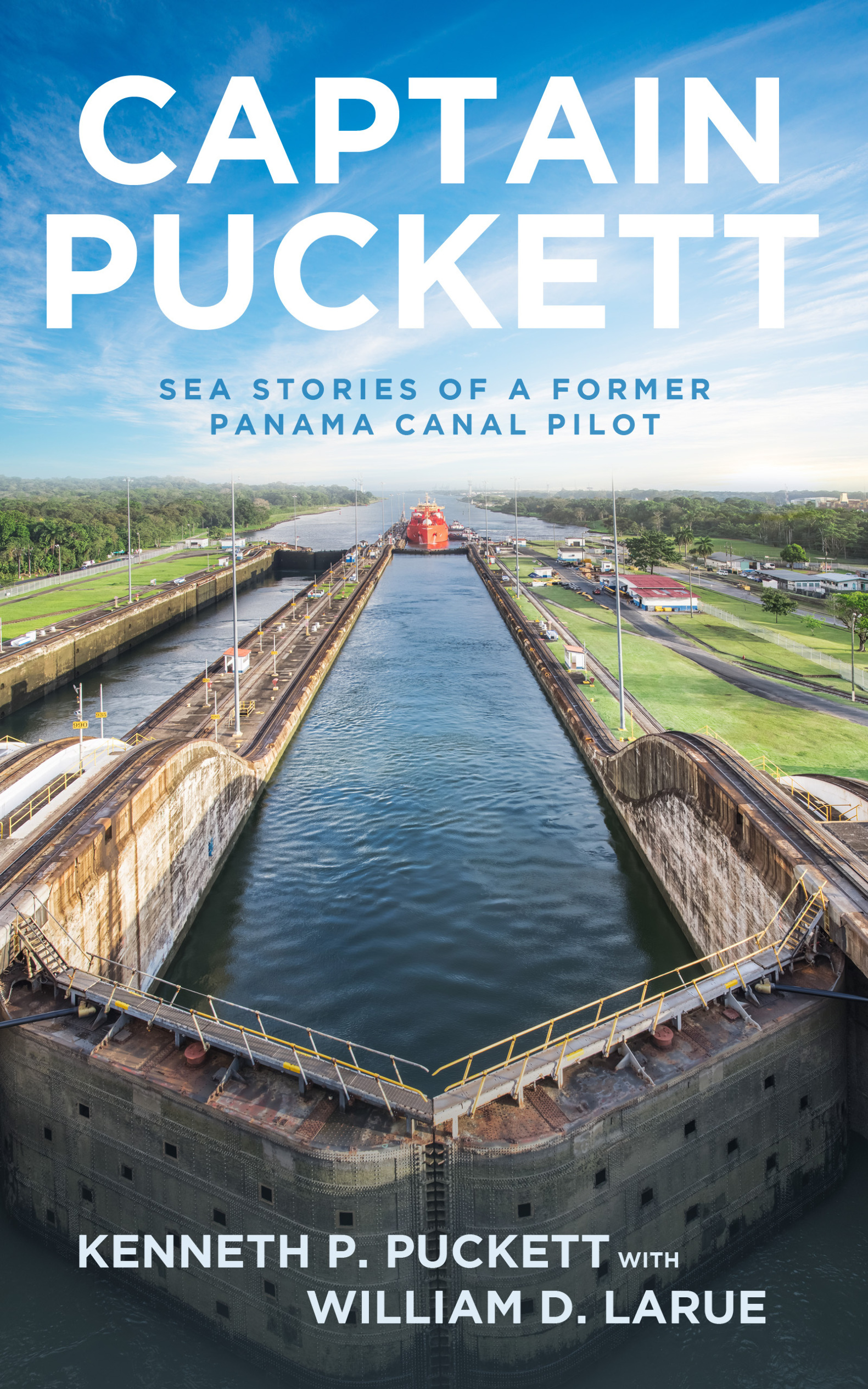

Cover design by www.ebooklaunch.com

Front cover photo by Jonathan Ross via Shutterstock

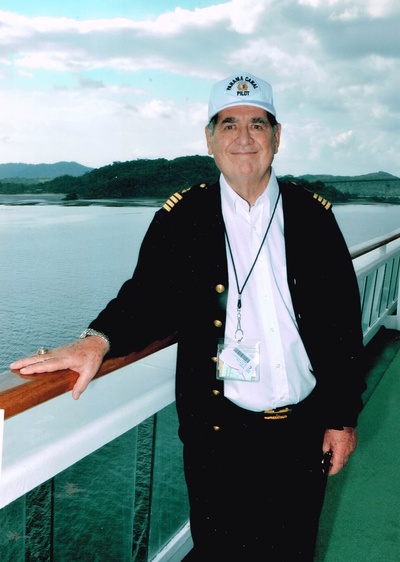

Back cover photo by Rick Thompson

e-book formatting by bookow.com

This book is proudly dedicated to U.S. Army Chief Warrant Officer Carter C. James, who was my mentor and much more.

Kenneth P. Puckett

Preface

I was sitting in an airplane not long ago, flying first-class because I had an upgrade, and the passenger in the seat next to me was a gentleman in his late 80s. We got talking a bit, and he told me he had been an engineer and had worked with NASA on the Apollo space program. Then he asked me what I did for a living.

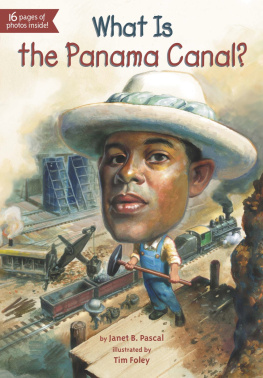

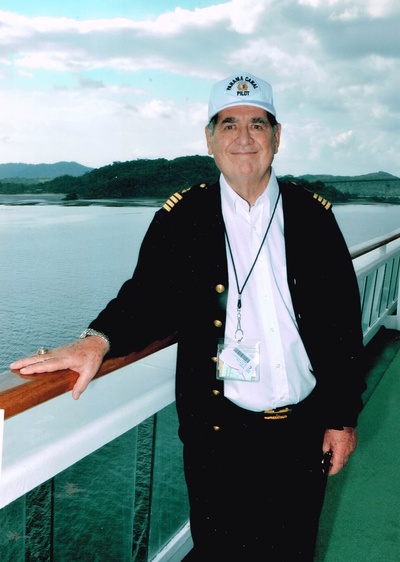

I stand on the bridge in my white pilots uniform as the P&O Cruises ship M/V Aurora passes through the Panama Canal in January 2016.

I told him I had been a pilot on the Panama Canal.

Youre a pilot? he asked. What did you fly?

I didnt fly anything, I said.

Now, this was a well-educated man trained in aviation, and he still didnt understand the difference between airplane pilots and maritime pilots. After he had a few drinks and fell asleep, I couldnt help but think how often over the years I encountered similar confusion when I told someone what I did for nearly 16 years on the Panama Canal. When a Minnesota newspaper ran a short item announcing I would be giving a lecture in April 2001, the headline read: Navy pilot discusses Panama Canal.

Let me give you a brief history of maritime piloting.

Long before the dawn of aviation, pilots helped to keep waterways safe. Pilots existed way back in ancient Egypt, and they are even mentioned in the Bible: And all that handle the oar, the mariners, and all the pilots of the sea (Ezekiel 27:29).

By the 14th and 15th centuries, a sailing vessel coming into an area would be greeted by a guy in a rowboat or fishing boat sitting out there and saying, Hey, I know the location of the harbor. I know the channel. I know the depth of the water. I know how the wind is going to be blowing. Ill guide you into port. Ill be your pilot.

The problem was, sometimes the pilot secretly worked for pirates, and he would deliberately run the ship aground, and the pirates would come aboard and steal everything. This method of piracy got so bad that, if a ship ran aground even accidentally, the captain would hang the pilot over the side and execute him as a warning to others.

Understandably, the legitimate pilots began to worry they were taking their lives into their own hands by helping the ships. To solve this, the pilots got together on the west coast of Europe to establish some rules and regulations. They got the kings to give them authority and a monopoly in exchange for making sure those who worked as pilots were checked out and found to be legit.

Then in 1514, the Corporation of Trinity House of England was established to regulate pilotage, and it set standards throughout the world that are still in operation today, including licensing of pilots. Today, there are about 80,000 pilots assigned to harbors, ports and canals around the world. Their job is to climb aboard arriving and departing ships to help their captains navigate waters and avoid hazards that can damage a ship, such as hidden reefs and tricky currents.

The pilots on the Panama Canal historically have been looked upon as among the best. In other places, a pilots only responsibility might be to bring a ship through a channel into a harbor or through the mouth of a river. Panama Canal pilots are required to be channel pilots, docking pilots and locks pilots. It requires tremendous skill for them to bring a ship through a complicated set of locks, often fighting wind and currents that can send the vessel into a wall. Then they take the same ship across a man-made lake where tops of trees lurk below the surface and through a mountain range where the edge of the waterway looms feet away. Even today, with GPS and radar and other electronic aids, a Panama Canal pilot who doesnt know what he is doing can put a big cargo ship very quickly into a muddy bank.

I went to work as a Panama Canal pilot in January 1981, about four years after U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Panamanian leader Gen. Omar Torrijos signed treaties in which the United States agreed to turn over the canal to Panama at the end of 1999. At the time, I was thrilled to get the job, unaware of the extent to which I had stepped into a hornets nest of anger, fear and bitterness among Americans living and working there. Many had called the Panama Canal Zone their home for generations. They had been living in an American Utopia with all sorts of benefits and privileges, from cheap housing to imported groceries, and now they resented the fact the treaties were taking that away.

When I arrived, I was one of 35 experienced captains recruited from across the country to replace Panama Canal pilots who had quit or retired after the treaties were signed. I was also among the half-dozen Pilots in Training (PIT) with military backgrounds. I had served in the Navy as master, mate, navigator and senior quartermaster on numerous ocean-going vessels for more than eight years. After transferring to the Army in 1966, I served as a ships pilot in Vietnam, Japan and South Korea. I also came under enemy fire delivering cargo on ships along the Vietnamese coast. While I was in the Army, I was trained, certified and licensed as a master/pilot and captained several vessels. When I retired from the Army in 1978, I held the rank of chief warrant officer CWO4.

I was almost 40 when I began working on the canal. Yet some longtime ship pilots resented me right away, treating me like a raw cadet. Many just didnt like military guys. They also resented that I hadnt come up through the U.S. Merchant Marine system and its good-old-boy network steeped in nepotism, which is how they got their jobs.

These guys also had a union mentality about everything, which I thought was stupid because they were employees of the federal government. I said to a pilot one day, You can act like you are union, but forget it. All you can do is negotiate your working conditions. Youre not going to negotiate your salary. And if you quit working, the federal government says, Goodbye. And thats exactly what happened in August 1981 to the air traffic controllers when President Ronald Reagan replaced them for going on strike.