The Making of a History

Walter Prescott Webb and The Great Plains

Gregory M. Tobin

University of Texas Press Austin

utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/rp-form

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Library ebook ISBN: 978-0-292-76944-1

Individual ebook ISBN: 978-0-292-76945-8

DOI: 10.7560/750296

Tobin, Gregory M 1936

The making of a history.

Originally presented as the authors thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1972.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Webb, Walter Prescott, 18881963. 2. Webb, Walter Prescott, 18881963. The Great Plains. 3. Great PlainsHistory. 4. Mississippi ValleyHistory. I. Title.

E175.5.W4T62 1976 978.0072024 [B] 763120

ISBN 0-292-75029-3

Copyright 1976 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

Set in Times Roman by G & S Typesetters, Inc.

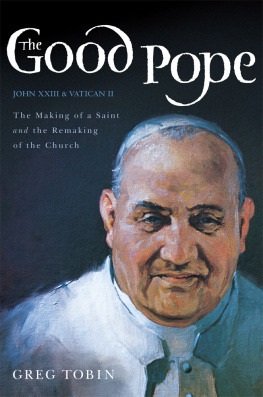

Frontispiece: Walter Prescott Webb by Alan E. Cober

To K. M. T.and our four close friends

Contents

IT IS A MEASURE of the standing of Walter Prescott Webb among his friends and associates that any request for advice and assistance made during the course of this study invariably met with a generous response. I am indebted to members of the Webb familyMrs. Walter Prescott Webb, Miss Mildred Webb, and Mrs. Ima Wrightfor their willingness to share their recollections with me. Mr. C. B. Smith, Sr., of Austin, Texas, made it possible for me to consult what proved to be a very important collection of Webb papers which had recently come into his possession. Dr. Chester V. Kielman of the University of Texas Archives and Dr. Dorman H. Winfrey of the Texas State Archives gave me every assistance in locating materials, as did the staff of the Barker Texas History Center. Professor William A. Owens of Columbia University kindly gave me access to a taped interview with Walter Prescott Webb recorded in 1953.

Webbs long association with the history department at the University of Texas at Austin meant that I could draw on the comments of a number of those who had worked with him in the later stages of his career, and I am grateful to Professor Barnes A. Lathrop, Professor Robert C. Cotner, and Professor Joe B. Frantz for their advice and assistance. The dissertation which eventually emerged owes a great deal to the careful and kindly attention of my supervisor, Professor John E. Sunder.

Many others contributed to the development of this study, and in ways that are difficult to categorize. The American Studies Program of the American Council of Learned Societies supported my research, and I am grateful to Mr. Richard W. Downar and his staff for making it possible for me to devote an extended period of time exclusively to writing. A travel grant from the Australian-American Educational Foundation helped me get to the United States, and the task of getting a program of graduate studies underway was made much easier than it might have been by the kindness of members of the Austin communityin particular, Professor C. Hartley Grattan and Mrs. Grattan, Professor Phillip L. White, and Gene and Betty White. There are others whose encouragement and friendship made an indirect but no less distinct contribution; for example, Emeritus Professor Norman D. Harper pioneered the study of American history in Australia, and my interest in the West dates from his courses at the University of Melbourne. Professor Howard R. Lamar provided me with detailed and helpful comments, and I am grateful for his interest in the work.

Finally, there are those who made it possible for me to complete the study by taking heavier loads on their own shouldersmy colleagues at Flinders, and in particular Trudi Hislop, Paul Bourke, and Don DeBats. Jenny Elliott and Sue Forrest helped type the final draft, Madeleine Davis and Carolyn Clementi checked sections of the manuscript, and Andrew Little prepared the map. The journey which took me eventually to the edge of the Plains, and the research and writing which were part of that journey, could not have been made without the encouragement and support of my family; this is their book, as much as it is mine.

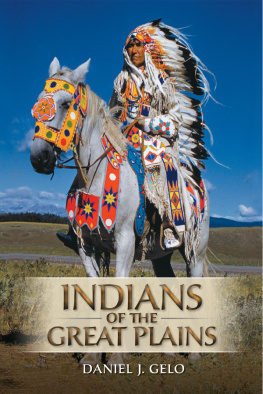

ROUGHLY ONE-FIFTH of the territory of the United States lies in the area generally designated as the Great Plainsa vast tract stretching from the eastern slopes of the Rockies to a nebulous line west of the Mississippi and in the vicinity of the ninety-eighth meridian. It was in this area that the last act in the long drama of American settlement was played out; as much as forty years had elapsed between the time of acquisition and the fact of settlement, and during that period the Plains were crossed and recrossed by itinerant trappers and by settlers moving through to the more attractive lands of the Pacific Coast. The image of the Plains as a great ocean of grassland and limitless horizons that had so appealed to earlier observers still held good at the midpoint of the nineteenth centurysave that there were now well-traveled sea lanes as well as empty expanses; an ocean that for centuries had supported its own distinctive life now felt the presence of strange craft and narrow lines upon its surface. Those who crossed took only what they needed for the moment; they showed no inclination to stay, for to them the Plains were simply a wide corridor to the Promised Land, and of no intrinsic importance.

In the thirty years that followed the end of the Civil War, the eastern heartland of the United States entered into the industrial age with a vengeance, and the products of its factories made it possible for the herdsman and the cultivator to mount the first concerted assault on the grasslands that stretched from west of the Mississippi to the Rockies. Urbanized northeasterners, who were only one generation away from their own roots in the soil, forged the rails that brought the iron age to the Plains; the nomads of the Plains and their seminomadic white counterparts made way for the pastoralist and the tiller of the soil, and the same technology that had brought these new inhabitants to the Plains made it possible for them to grow food for those who tended the machines, both at home and abroad. For a brief period two different stages of development stood side by side on the one continent and within the one civilizationthe city and its processing mechanisms, the Plains with their meat and grain. Though closely interlocked, heartland and colony stood for a moment sharp and clear within a single polity; a generation later, and the lines of demarcation were already becoming blurred.

The elements of contrast should not be overstressed; most of those who settled the Plains in those decades had been reared in the framework of a common cultural heritage and took with them a general commitment to a common set of values and assumptions that already had the weight of a century of national life behind iteven allowing for the great trauma of the Civil War. The relatively few cultural differences that did survive into the second half of the nineteenth century had little chance of prevailing against the impact of a catapulting technology that eradicated distance and laid conduits for the printed and spoken word across even the most extensive deserts and plains. Colonial appendages though they were, the settled areas of the new West were not allowed to savor their physical isolation for very long; incorporation proceeded alongside development and exploitation, ensuring the extension to the West of that larger sense of identity that marked the American off from the world community. So effective was this process of continuous assimilation and cross-fertilization that within a generation a distinctively western typethe cowboyhad won acceptance as a symbol at the national level.