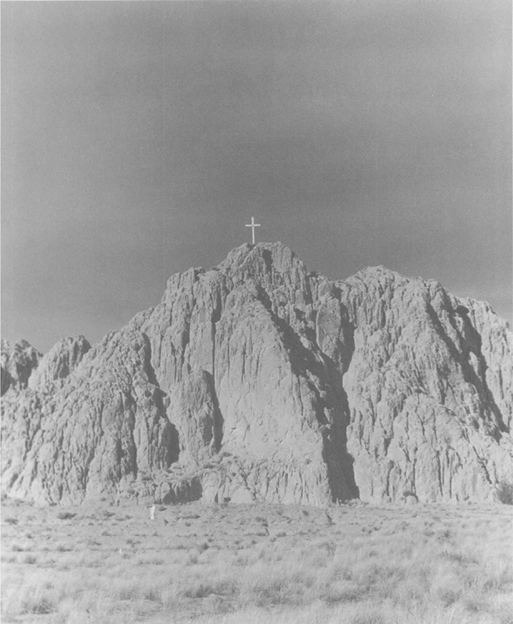

Cross from the highway, near Nambe, New Mexico, 1963

Photographer: Todd Webb

Courtesy of Todd Webb and Olaf Olaf

INTRODUCTION

We listen to our inmost selves

and do not know which sea we hear murmuring.

MARTIN BUBER , Ecstatic Confessions

W HEN THE anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski was studying sex and trade on a South Sea island, he confessed in his private diaries to feeling by turns ultimate mastery and elements of worry. Mastery flowed from collecting data and documents that would build his professional reputation. Worry arose from what Malinowski called the atmosphere created by foreign bodiesespecially those of naked women who unselfconsciously displayed the beauty of the body so hidden to us, whites. Enthralled and confused, the ethnographer struggled to maintain his focus on work and to resist hating the Trobriand islanders as animals who aroused his lust and excited his fear of losing control. He guarded against the women by defining himself as a white man who could not indulge in sexual dalliances or masturbation because of moral tenets; and he graded himself on how well each days thoughts and conduct measured up.

But Malinowski was less certain about how to handle another temptation, one more subtle than the lure of women but connected somehow, he sensed, with them: a feeling of letting myself dissolve in the landscape, moments when you merge with objective realitytrue nirvana. When these sensations came over him, Malinowksi gave himself a good shake, checked to make sure he was not developing fever, and plunged back with determination into his data and abstract theory. He wanted to get back to his intellectual work and shrugged off as a forbidden desire the impulse towards merging.

In the Western tradition, the kind of shrugging off Malinowski enacted in the Trobriands has been a frequent gesture. Yet the attraction to merging with objective reality has also been persistent. My claim in Primitive Passions is that the West has tended to scant some vital human emotions and sensations of relatedness and interdependencethough it has never eliminated them. These sensations include effacement of the self and the intuition of profound connections between humans and land, humans and animals, humans and minerals, of a kind normally found in Europe and the United States only within mystical traditions. The link between such sensations and primitive peoples, while it is not inevitable, is, I will show, neither trivial nor incidental in the Western imagination.

The word primitive is sometimes used in a derogatory sense to mean simple or crude, with evolutionist connotations of inferiority. That is not how I use the word, which has a rich history of alternative meanings. In its most generalized sense, primitive refers to a posited but ultimately unknowable original state, whether of humans or of animals, nature, tissue and cell, or of religious and social institutions. It entered the English language with special reference to the Christian church; only later, in the eighteenth century, did it come to refer to cells, nature, and indigenous peoples. Today, the primitive often refers to specific groups living traditional lives (the Asmat in Irian Jaya, the Yanomani in Brazil, and many others)but it also encompasses a great deal more. The primitive denotes the eons of prehistoric human experience; it refers as well to societies such as the Aztecs, with highly developed but now mysterious or exotic-seeming ancient histories. Most of all, the primitive describes a vast, generalized image, an aggregate of places, things, and experiences associated with various groups and peoples: Africa, the Amazon, or the American Southwest; communal drumming and ecstatic dancing; initiation and other rituals that express respect for the powers of nature and the supernatural.

Properly speaking, primitivism refers not just to an interest in or borrowing from indigenous groupsthough that is how the term is commonly used today. In fact, this is an important, but relatively late meaning, and one that should be informed by the recognition that, contrary to the practice of many primitivists, primitive peoples are diverse in terms of their social systems and beliefs and typically exist today in contact with the modern world. Primitivism inhabits thinking about origins and pure states; it informs desires for known beginnings and, by extension, for predictable ends. Primitivism is the utopian desire to go back and recover irreducible features of the psyche, body, land, and communityto reinhabit core experiences. This book probes all of these meanings of the term, with special attention to connections enacted in modern lives between primitivism and spiritual emotions.

Primitive Passions widens and deepens a journey I began in Gone Primitive, which critiqued mens representations of Africa and the South Pacific and primitivisms damaging effects both in the West and abroad.

As I wrote Gone Primitive, I was tantalized by the way in which men like Malinowski repressed some of their strongest positive feelings for the primitive, what he called the nirvana impulse and other thinkers of his day called the oceanicbest defined as a dissolution of subject-object divisions so radical that one experiences the sensation of merging with the universe. I came to understand that a comprehensive psychology of the Wests fascination with the primitive would require a broader consideration of male encounters with the oceanic, as well as an understanding of a variety of female responses to comparable experiences.

Fortunately, there were several odd things about how the men I had studied used motifs like human sacrificeoddities that inspired my curiosity. Cannibalism, human sacrifice, and head-hunting apparently did not and do not really exist within most indigenous cultures or, at the very least, the extent of their practice has been wildly overstated in the West. In fact, Europeans and Americans seem to have been so obsessed with the consumption of human flesh and the hunting of heads that they described in macabre or bizarre detail practices that often either were not present or did not function in a morbid way among indigenous peoples. Indeed, when genuine cannibalism and head-hunting have been documented, they have been revealed to have specific spiritual or purgative functions and an exquisitely detailed etiquette.