For Lily

Every encounter with the Other is an enigma, an unknown quantityI would even say a mystery.

RYSZARD KAPUSCINSKI

Contents

1

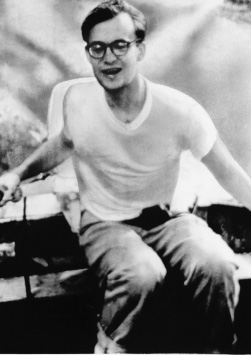

November 19, 1961

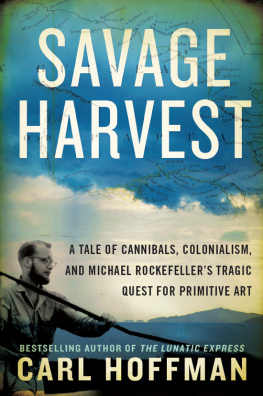

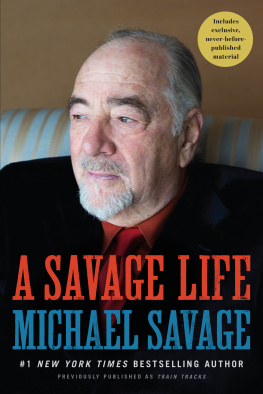

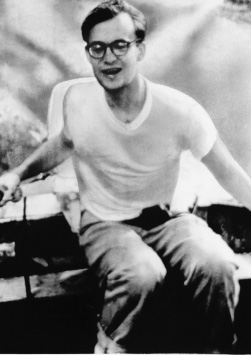

MICHAEL ROCKEFELLER IN NEW GUINEA.

( Library of Congress )

THE SEA FELT warm as Michael Rockefeller lowered himself in from the overturned wooden hull. Ren Wassing peered down at him, and Michael noticed Ren was sunburned and needed a shave. Their exchange was brief. Theyd been drifting on the ocean off the coast of southwest New Guinea for twenty-four hours now, and there wasnt much that hadnt been said.

I really dont think you should go.

No, itll be okay. I think I can make it.

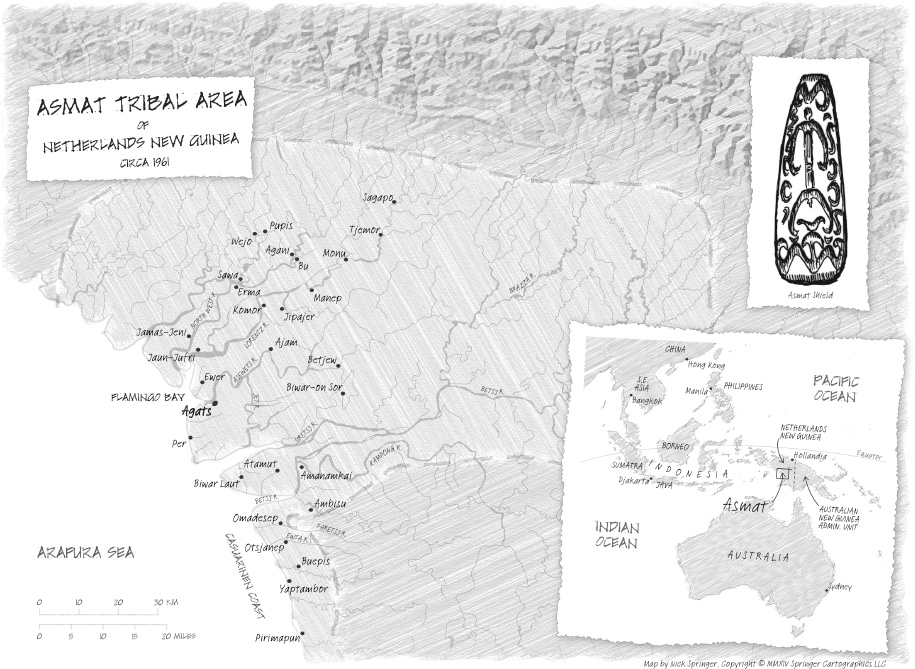

Michael cupped his hands and swung his arms, swiveling around. It was eight a.m. The tide was high. He was wearing white cotton underpants and thick, black-rimmed glasses. He had two empty gasoline cans tied to his webbed, military-style belt. He hugged one tightly and started swimming, kicking toward the coast, a hazy line of gray, barely a smudge. He estimated they were five to ten miles off the coast. He kicked slowly and ran the numbers. A mile an hour and hed be there in ten hours. A half-mile an hour and hed reach shore in twenty. No problem. The sea was almost as hot as a bath, and it was just a matter of setting his mind to the task. Plus, he and Ren had the tide charts for the coast and he knew something else in his favor: the tides werent evenly spaced right now. Between four p.m. and the next morning, there would be a high tide at midnight, a brief low tide at two a.m., and then another high tide at eight a.m. Which meant that for twelve of the fourteen hours between four p.m. and the next morning, the water would be pushing him toward the coast when he was the most tired.

It wasnt long until there was no more Ren on the overturned catamaran behind him. He knew that feeling from swimming off the coast of Maine every summer, how the shore behind you receded quickly even when the destination didnt seem any closer. And the Arafura Sea here was shallow. He ought to be able to stand, to touch the muddy bottom, when he was still a mile from shore. He rolled onto his back and kicked, long, slow, steady kicks, dragging the cans. He could hear his heart thumping and the sound of his own breathing.

He never would have said it out loud, but he carried a sense of destiny. A bigness. A self-confidence he was barely aware of. Twenty-three-year-olds dont think about death; life seems eternal, the same as when he would speed along the Maine Turnpike in his Studebaker doing eighty. Now was everything to a twenty-three-year-old. Plus, he was a Rockefeller. Sometimes it was a burden, sometimes a gift, but it defined him, even when he didnt want it to. Cant wasnt part of the family lexicon. Everything was possible. He had grown up being able to go anywhere, do anything, meet anyone. His great-grandfather had been the richest man in the world. His father was governor of the state of New York, had just run for president of the United States. In epic survival situations, will is everything, and Michaels was as big as a will could be. He carried a responsibility, every Rockefeller did, to do good things, big things, to make something of himself. Stewardship was the word the family used. He wasnt just swimming for his life. He was swimming for Ren, who needed to be rescued. He was swimming for his father, Nelson. For his twin sister, Mary. For the Asmat themselves, in a way, because he had collected so much of their beautiful art that he wanted to share with his father, with Robert Goldwater at the Museum of Primitive Art, with his best friend, Sam Putnam, with the world. He didnt exactly articulate this, he just knew it, felt it. So he swam and stroked and kicked with confidence. It was a big world, but he was in a bubble. Him and the sea, the big Arafura.

He wasnt in a hurry. Fear, panic, those were what killed people, made their minds crazy, frantic, exhausted precious energy. He remembered that from army basic training. And he even smiled a little, recalling how he and his Harvard classmates had rolled their eyes at the Widener swimthe requirement that every Harvard graduate complete a fifty-meter swim before graduation, stipulated by the mother of former alum Harry Elkins Widener, whod died on the Titanic, when she gave $2.5 million for the schools new library. This was a matter of steadiness. When he felt his calves starting to cramp, his shoulders tiring, he rested, floating, clinging to the gasoline cans, staring at the big sky full of shifting, changing clouds overhead. Luckily the wind and the sea were calm, and they grew calmer as the afternoon passed. At sunset, the ocean was as still as a swimming pool on a summers eve. He swam on. He thought about the exhibition he wanted to mount in New York. The feast poles twenty feet tall hed collectedno one had ever seen anything like that in the United States before; they would dwarf anything else in his fathers new museum. The stars came out, billions of them. Heat lightning flashed along the horizon. The moon rose, three days from full, and he wasnt in total darkness.

He swam on.

He wasnt sure where he was, but probably somewhere between the Faretsj and the Fajit Rivers, between the villages of Omadesep and Basim. By dawn thered be people along the shore, for surethey were always there fishing. He was happy with how well he already knew these people; Asmat, this remotest corner of the world, had become his. His universe, an alternative world that hed discovered, was untangling, and this swim to shore was like a baptism, deep in Asmat, and it would be a good story to tell. It was dark and had been for a long time when he saw strange reflections on the water. Behind him the sky lit, white, the light of phosphorescent flares dropping toward the sea. He saw them, but he didnt know what they were.

Around four a.m. the sky started to turn faintly purple, first light. Out here Michael could feel those subtle shifts. He had been swimming for eighteen hours, but it was almost done, he knew, if he could keep going. His waist was raw where the belt holding the floats was chafing. He was exhausted, but the dawn gave him some added strength. He could see the trees more clearly now. They were a dark line, but they were there. He rested again. Floated again. His whole body hurt. He was thirsty and hungry, and the salt water stung. Hed do anything for a long drink of cold, fresh water. He shivered. Best keep going. As the day got lighter, brighter, he got closer. He tried to touch bottom and he could. Barely. It was mud, though, slippery and sticky, and it was easier to swim. But he could stand and rest, and just knowing that was everything. He knew he would make it. He untied one of the empty gasoline cans and let it go; it was easier without it. He swam, he stood, he swam some moreon his back now, really the only way to make progress, even though it hurt. He was almost safe. Nipa palms and mangrove rose seemingly right from the water, and among them canoes, a flotilla of them nestled in the trees.

And men.

2

November 20, 1961

AN ASMAT ANCESTOR SKULL. THE LOWER JAW IS ATTACHED, INDICATING THAT THE DECEASED WAS NOT THE VICTIM OF A HEADHUNTING RAID.