Contents

PART ONE

ONE:

TWO:

THREE:

PART TWO

FOUR:

FIVE:

PART THREE

SIX:

SEVEN:

EIGHT:

NINE:

TEN:

ELEVEN:

TWELVE:

PROLOGUE

Time for Prayer

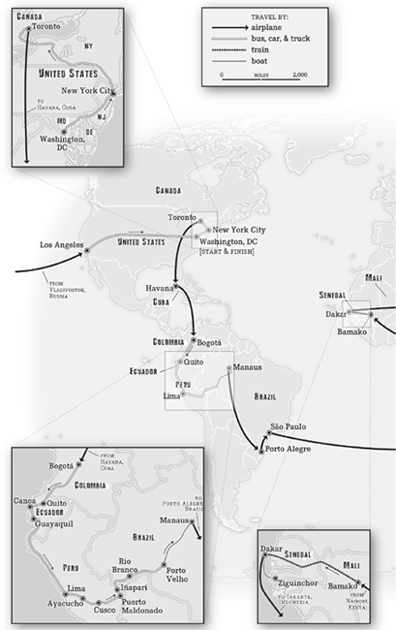

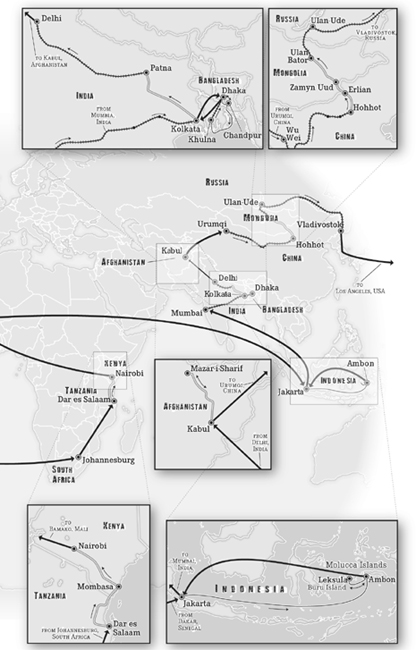

O UTSIDE OF P UL-I -K HUMRI , the bus shuddered to a halt on the dusty roadside and couldnt be restarted. Khalid, my traveling companion, sighed. Fretted. I rose to go outside and stretch my legs like everyone else, but Khalid stopped me. This is bad, he said in a whisper. It is a dangerous place. It is the home of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. He is the most dangerous man in Afghanistan. Very religious, the leader of the Islamic Party of Afghanistan. It is the party of violence and killing of innocent people. He is not Taliban, but just as bad. He lives in exile now, but his people are here. Khalid, I knew, was right. Hekmatyar had been politically all over the place, but since the fall of the Taliban hed been violently opposed to both the Karzai government and the American presence in Afghanistan. Hed been officially labeled a terrorist by the United States. I suddenly had a terrible feeling. A feeling of dread, worse than at any time since Id left home months ago to journey exclusively around the world on its most dangerous and crowded and slowest buses, boats, trains, and planes. My knife was taped to my arm and I was dressed in a grease-stained salwar kameez, with a hat pulled low over my head and a weeks growth of beard covering my face, but out here what good would it do if we had to stop moving for a day? Where would I go? Where would I flee? There was no taxi to jump into, no government ministry or five-star hotel in which to hide. Outside were brown fields. A few mud houses. Bare trees. What if the bus couldnt be restarted? What if we had to get off and wait in town and I was discovered? I was crazy for trying to ride a bus across Afghanistan in the middle of a war; idiotic. What had I been thinking? I closed my eyes and tried to fall asleep, to think about nothing.

Khalid prayed.

PART ONE

AMERICAS

AMERICAS

A Russian-made Cuban commercial jet smashed into the side of a mountain near the Venezuelan city of Valencia on Saturday night, killing all twenty-two people on board, authorities said today. There was no immediate explanation for the crash, the second major accident in less than a week for the state-owned airline.

New York Times, December 27, 1999

ONE

Go!

G O, GO, GO! yelled a Chinese woman in front of the New Century Bus office, a yellowed, basement room in an old federal row house on H Street Northwest, in Washington, D.C.s anemic Chinatown. The bus was around the corner. It was leaving. Now. It was cold and bright and my children and Lindsey, my wife, ran with me and we hugged and a Chinese man in a black leather jacket barked Go! and the next thing I knew I was alone, rolling down K Street on a so-called China bus to New York City. My phone chirped. A text from Lindsey: I wanted a picture of all of us! There had been no time. It seemed like a voice, fading, from up a river on which a current was sweeping me away.

The weather was unsettling, as it always is in the first weeks of March. The day before had been hot and cold and sunny and rainy and cloudy and windy all at the same time. Walking down Columbia Road with ten hundred-dollar bills fresh from the ATM in my pocket, squinting into the sun and clouds and trying not to get blown away by the gusts, I even got hit with hail the size of peas. Stop signs whipped back and forth, and a Washington Post news box crashed to the ground. I had a lump in my throat. My chest was tight. I hadnt slept well for weeks. In the morning I was leaving home.

For twenty years I had been a stable husband and father, and then Id snapped. My life suddenly didnt seem to fit anymore. I was middle-aged, with a wife and three children whom I loved but hadnt been living with for almost a year. A long journey seemed the best solution. The classic move was to leave the world for the exotic to be born anew: Gauguin shipped himself off to Tahiti, Wilfred Thesiger to the Empty Quarter; the New York artist Tobias Schneebaum literally shed his clothes by the Madre de Dios River and walked naked into the Peruvian Amazon. Its oppositethe search for raw pleasurehad long been popular, too: food and cafs in Rome for Henry James, and for Liz Gilbert, the spiritual groove of Balis Ubud.

As I fought my way through the wind down Columbia Road to finish packing in my barely furnished apartment, I had something different in mind: to escape not out of the world but right into its messy heart. To experience travel not as a holiday, but as it is for most people: a simple daily act of moving from one place to another on the cheapest conveyance possible. A necessary part of life, like brushing your teeth or sleeping or making love.

The idea first struck on a flight from Kinshasa to Kikwit in the Democratic Republic of Congo, while traveling on a magazine assignment. The thirty-year-old, eighteen-seat Short Skyvan was full, hot as an asphalt roof on a summers afternoon and buzzing with flies, and there was some doubt about when it would leave or if it would leave at all. Planes in the Congo were crashing with alarming regularity; my worry wasnt whether Id get a meal, but whether I might live or die. And we were lucky; we were flying. Below us was a country the size of Western Europe, with just three hundred miles of paved roads on which hordes of people were packed into thirty-ton trucks traveling on dirt tracks.

By road or by air, none of the people moving around the Congo were tourists. My fellow passengers in the Skyvan were sweaty and nervous, but resigned to delays and waiting and discomfort. Maybe that was how all travelers had once felt, I thought. For most of human history, travel, after all, was an arduous necessity. The word itself comes from the French travaillerto toil or labor, reflecting the difficulty of going anywhere in the Middle Ages. Aside from a few freaks like William Lithgow, a Scotsman who wandered through Europe, the Near East, and northern Africa in the early seventeenth century, people traveled not for the pleasure of it but because they had tolong journeys by foot or horseback or wagon or sailing ship that were uncomfortable and unpredictable and scary. Roads were bad. Ships sank. Today, however, we think of travel as joy-seeking, the pursuit of pleasure, a vacation, and tourism is the largest industry on earth, generating $500 billion a year in revenue. But tourism is a relatively new phenomenon, barely three hundred years old. As a journalist who frequently ended up in some of the worlds oddest corners and crevices, I gradually began to realize that the big numbers of todays tourism industry obscured a parallel reality, excluded a whole river of people on the move. Excluded, in fact,