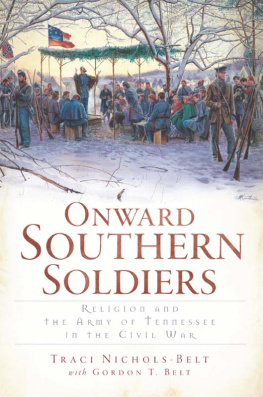

THE LIFE OF JOHNNY REB

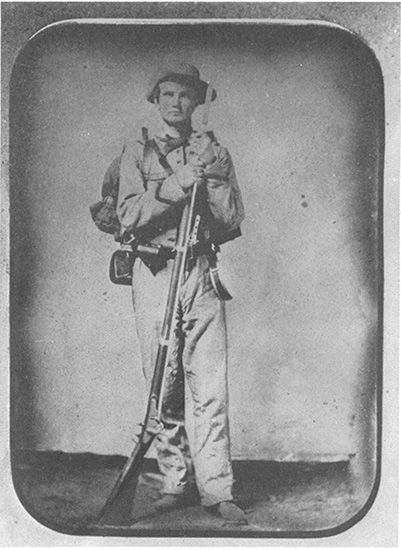

Courtesy Confederate Museum, Richmond, Virginia

A JOHNNY REB

Thomas Taylor, Private, Company K, 8th Louisiana Regiment. He served under Stonewall Jackson, was wounded at Sharpsburg and taken prisoner.

The Life of

JOHNNY REB

The Common Soldier of

the Confederacy

BELL IRVIN WILEY

With a New Foreword

by James I. Robertson, Jr.

Updated Edition

LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS

BATON ROUGE

Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright 1943 (renewed 1970), 1971, 1978 by Bell I. Wiley

Reissued by Louisiana State University Press in 1978

by special arrangement with author

Foreword copyright 2008 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Updated edition, 2008

Third printing

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 71-162618

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wiley, Bell Irvin, 1906-1980.

The life of Johnny Reb : the common soldier of the Confederacy / Bell Irvin

Wiley. Updated ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: Indianapolis : Bobbs-Merrill, 1943. With new foreword.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8071-3325-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Confederate States of

America. ArmyMilitary life. 2. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 1861

1865Personal narratives, Confederate. I. Title.

E607.W5 2008

973.782dc22

2007033859

The paper in this book meets the guidelines

for permanence and durability of the Committee on

Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the

Council on Library Resources.

To

M. F.

Then call us Rebels, if you will,

We glory in the name,

For bending under unjust laws,

And swearing faith to an unjust cause,

We count as greater shame.

Richmond Daily Dispatch, May 12, 1862

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

FOREWORD

The essence of history is people, Bell Wiley adamantly believed. History deals in large measure with human beings, and I know of no better way of understanding people of past times than through the study of their personal papers and personal papers of their intimate associates (Hill Jordan et al., Bell Irvin Wiley Reader, 2001, p. 184).

Wiley had a distinguished career as a Civil War historiannot because he concentrated on battles and leaders but because he championed the common folk, white and black, of that age. For most historians, inanimate red and blue arrows on battle maps signified tactics. To Wiley, the arrows represented thousands of plain individuals who were the backbone of America. He constantly searched for their letters, diaries, and recollections. After all, they were the ones who fought the battles, filled the cemeteries, and set the course of history.

A few months after Appomattox, a Confederate veteran ruefully observed that historians would hardly stop to tell how the hungry private fried his bacon, baked his biscuit, smoked his pipe (Walter Lowenfels, Walt Whitmans Civil War, 1961, pp. 293-94). That lament remained accurate for three-quarters of a century until the appearance, in the midst of World War II, of The Life of Johnny Reh (Indianapolis, 1943). The study was the first and most complete portrait ever painted of Confederate soldiers. With that book as a springboard, Wiley pursued research and writing on his way to becoming the pre-eminent social historian in the field of Civil War military history.

He could empathize with the common people because he had their roots. Born January 5, 1906, in former cotton country north of Memphis, Bell Wiley was in the middle of eleven surviving children. His father was a minister-teacher-farmer; his mother also taught school. Yet the income for so large a family came principally from growing sweet potatoes on a farm lacking electricity. The Wileys knew well the agrarian spirit of the Old South.

However, by determination and hard work, all eleven siblings attended college. The classroom was always Bell Wileys first love. After high school studies, he taught summer school for two months. In 1928 he received his bachelors degree from Asbury College, a Methodist school in nearby Kentucky. The following year Wiley obtained a masters degree at the University of Kentucky. Part-time teaching at Asbury helped defray the costs of that education. His masters thesis treated of cotton and slavery in Kentucky.

At the age of twenty-three, Wiley entered Yale University in quest of a doctorate. He wished to study under Ulrich B. Phillips, hailed by many as the leading historian of the antebellum South. Wileys longtime interest was the dilemma of the common people ensnared in the great conflict of the 1860s. He once told a reporter: I grew up with the Civil War. My maternal grandfather was a very young Confederate soldier in the Army of Tennessee. Wiley barely knew this forebear, but his grandmother lived into Wileys graduate school years. She was a splendid Christian woman, he liked to recall, but her Christianity was never broad enough to embrace love of Yankees (Army Museum Newsletter, July 19, 1980, p. 4).

Classmates at Yale remembered Wiley as tall, lanky, friendly, and too hard-working to have time for weekend frivolity. Completion of his dissertation became a race with time. Phillips contracted fatal throat cancer. Final directions from mentor to student were written notes. Phillips did not live to see the study become Wileys first book, Southern Negroes, 1861-1865 (New Haven, 1938).

Wiley had lasting pride in his Yale affiliation. His academic hood always hung on the back of his office door. No formal certificates of any sort were on the walls of his longtime Emory office. Every inch of wall space, from floor to ceiling, consisted of book shelves jammed to capacity.

In 1934 Wiley began his academic career as professor and departmental chairman at Mississippi Southern College (now the University of Southern Mississippi). The shaky financial situation of the Great Depression years forced Wiley to teach summer school at Peabody College in Nashville. There he met student Mary Frances Harrison. The couple wed in 1937. She became his constant companion, chief researcher, principal critic, andby Wileys assertiondeserving of credit for coauthorship of his first major book.

During 1938-43, Wiley served as professor and department head at the University of Mississippi. There he developed a lasting friendship with William Faulkner. It endured, according to Mrs. Wiley, because Bell didnt constantly bring up the great novelists work (James I. Robertson, Jr., and Richard M. McMurry, Rank and File, 1976, p. 4). It was also in the years at Ole Miss that Wiley produced The Life of Johnny Reb as well as The Plain People of the Confederacy (Baton Rouge, 1943), a series of lectures on the common soldiers, the home folk, and black Southerners.

World War II then interrupted his professorial career. Wiley entered service as a first lieutenant on the staff of General Benjamin Lear of the Second Army. Working with Chief Historian of the Army Kent R. Greenfield, Wiley coauthored two books on ground combat troops. He found writing history as it was being made to be an unforgettable experience. By the end of the war, Wiley was a lieutenant colonel and recipient of the Legion of Merit award.

Next page