This anthology has been divided into chapters to show the different faces of craft. The craftspeople themselves and their work, however, are by no means limited to these chapter headings. All the creative people featured here make work that is imaginative, playful, profound, honest and far-reaching. They cannot be described by any categories.

The crafts tradition is long and rich, and we have not attempted a historical overview. We have focused on living craftspeople, most of them still producing. Even so, this could not begin to be a comprehensive representation of the many wonderful craftspeople working today. The inspiration for the book was those articles already printed in Resurgence, and we supplemented these in order expand the breadth of crafts covered. There are many whom we would have liked to include, but did not have appropriate material or space. We apologize for these absences.

Thanks go to June Mitchell for valuable editorial advice and assistance. Thanks go to Karen Holmes for administrating and co-ordinating the work. Thanks go to the Crafts Council for sponsoring the book by providing financial support.

Special thanks go to the many photographers who have so generously given us use of their work.

Finally, thanks go to all the contributors, writers and craftspeople who have kindly permitted us to use their artwork and articles in this anthology, free of charge.

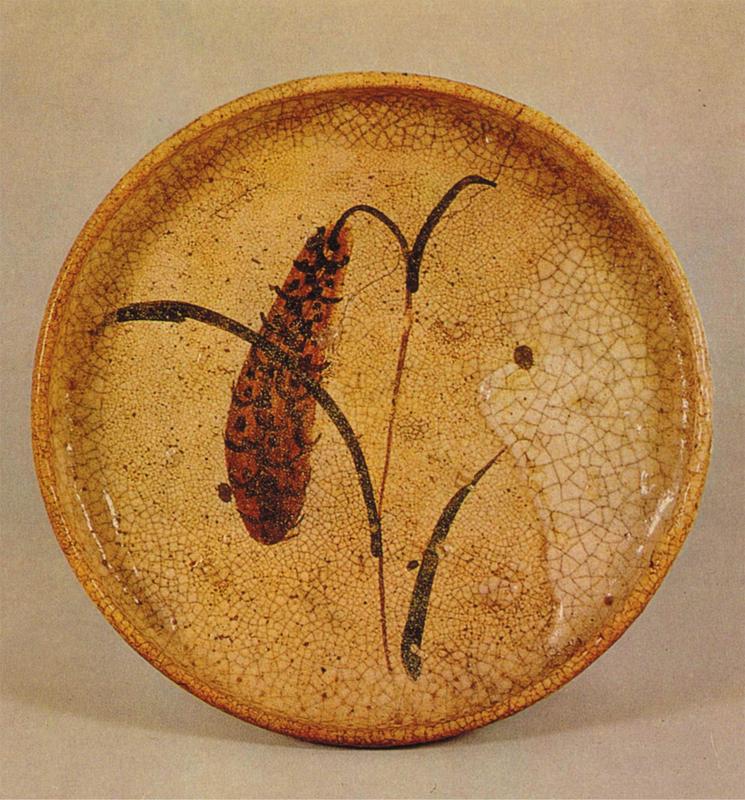

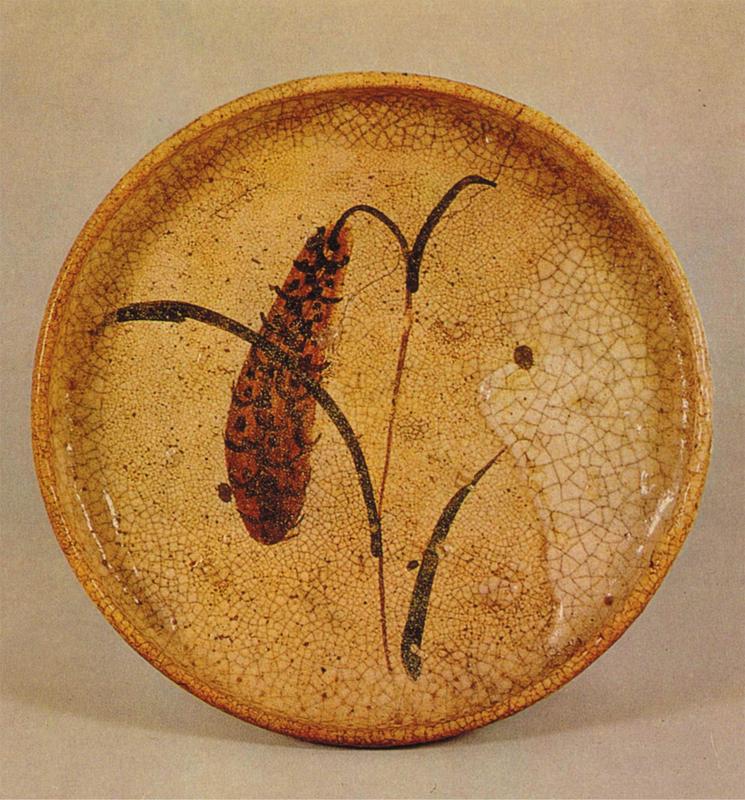

17th-century Japanese Shino-type stoneware plate.

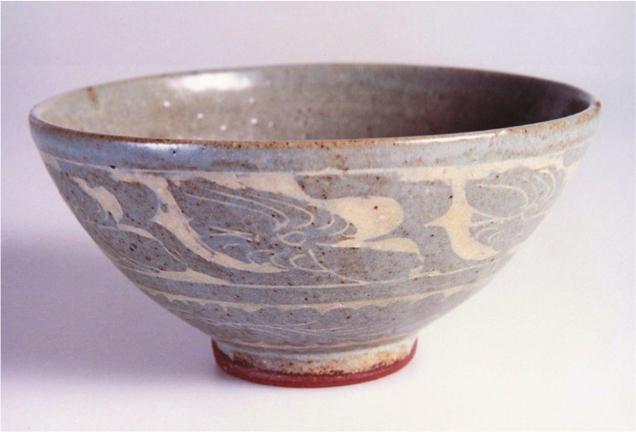

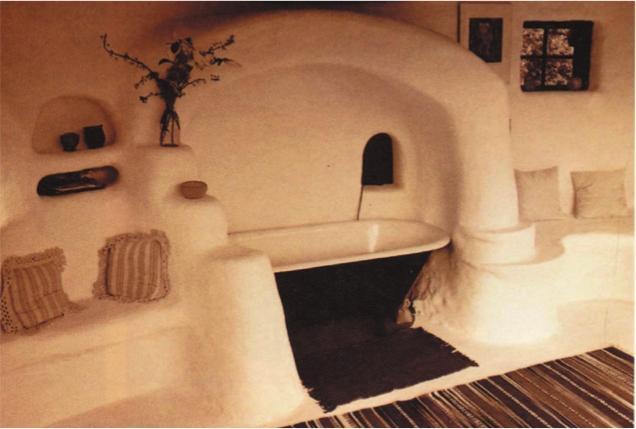

When the plate we eat from, the bowl we drink from, and the spoon we hold in our hand are works of art, then our lives are enriched every day.

BY SANDY BROWN

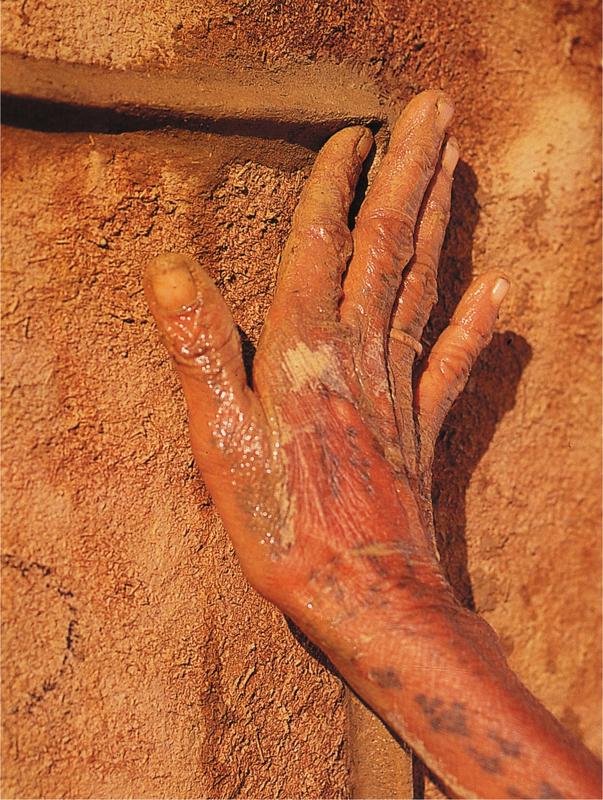

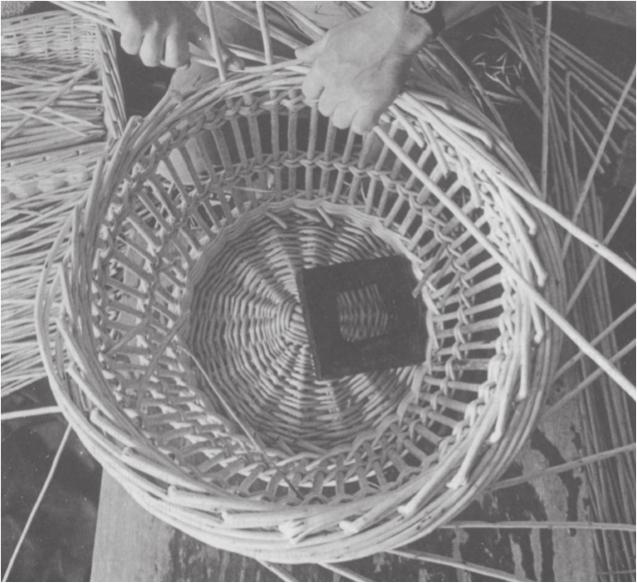

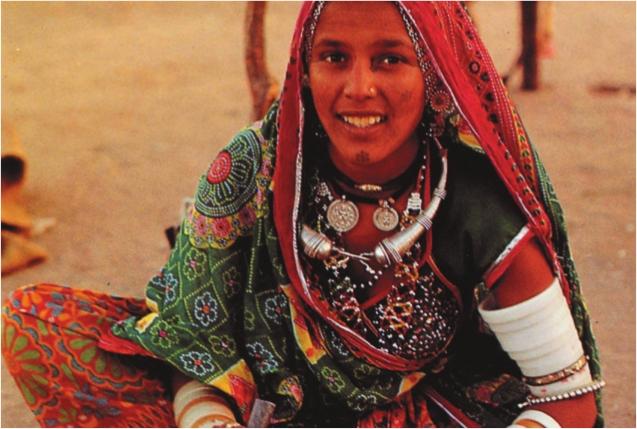

T ANYA HARROD, in her magnum opus Crafts in the 20th Century, says that craftspeople are those who gather inordinate joy in labour. This is true: the pleasure obtained in making, in expressing oneself through handling the materials, through experiencing the sense of touch and developing a fulfilling visual vocabulary is certainly something that drives the makers in this book. They have an intimate affinity with their chosen materials, just as a loving mother has an intimate affinity with her baby. In fact, this affinity with the chosen materials is the love-affair which characterizes craftspeople. And it shows in the work. Whatever the maker is feeling during the making is captured in the work. When that feeling is love, joy in labour, it is there in the materials, in the very fibre of the piece. There for us all to receive. And just as a loving parent can facilitate a child rich in the sense of her- or himself, so a loving craftsperson who is an artist can facilitate a work of art rich in its sense of being. The best craftspeople are artists.

The craftspeople featured in this book are those whose work has a spiritual dimension. This comes from working intuitively; from developing a meditative sense of the here and now. Working intuitively means that often what the idea is, if there is one, is not apparent until after the work has been produced. Working intuitively means playing, starting with an empty mind not knowing where one is going. It means working on the periphery of ones consciousness; being open to accidents.

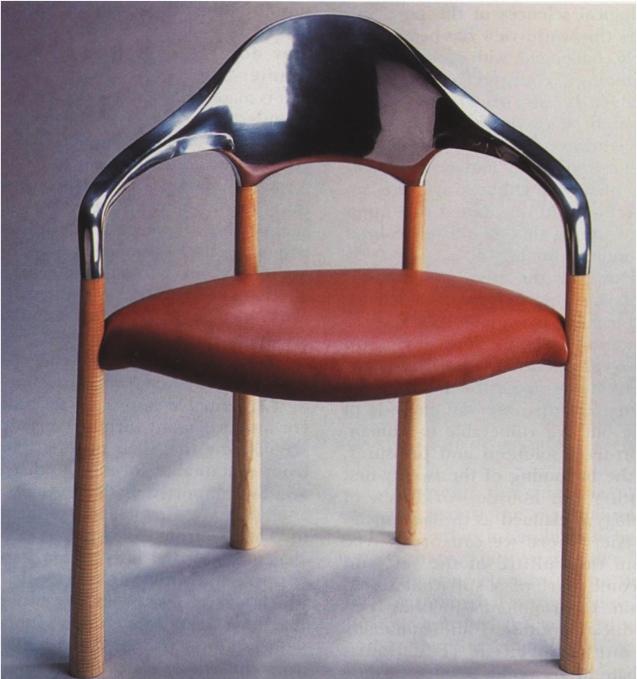

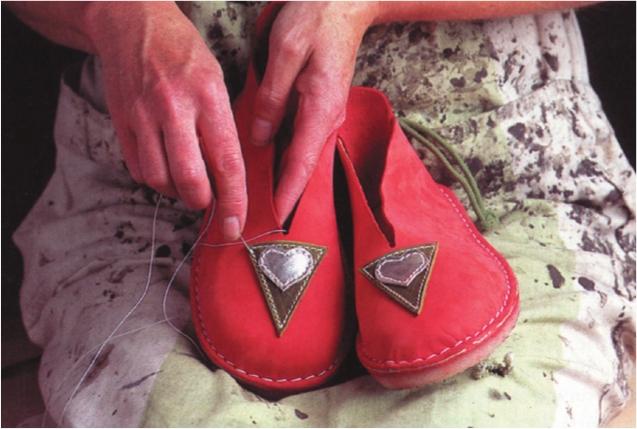

The work of most craftspeople has its roots in the function of objects, even if from those roots many makers are increasingly branching into making work which is sculptural and abstract, concerned with form, colour and the expression of a visual language. I do so myself, and enjoy the freedom it offers as we expand into new territories. This enlarges our sense of what is possible. And it further fuzzes the boundaries between art and craft.

But it helps enormously in the appreciation of crafts to know the nature and context of the historical roots, just as it does in any art form. Each person who starts working in clay, metal, wood, or textiles, as he or she develops the love for their materials, inevitably wants to know everything about their chosen material, what has been made in it during the previous several thousand years, and whose work they admire most. All of this knowledge of the history and culture of their chosen material will feed their creativity and inform their current contemporary work. This cultural history of contemporary crafts deserves to be more widely known.

As the mainstream Art world moves more and more away from things, and into concepts, video, ideas and intangibles, the Crafts become increasingly important. Crafts are therefore expanding and being seen in our culture to occupy the whole spectrum of actual hand-made pieces; of things which exist in real three-dimensional space and which you can touch.

William Morris and Soetsu Yanagi (author of The Unknown Craftsman) would be astonished to see the Crafts in such a healthy state in our high-tech post-industrial age. In some ways it is thanks to their enthusiastic advocacy of, as they saw it, humble craftspeople, that we today have so many people engaged in making things. Yet they were wrong to criticize the artist-craftsperson, as they are the source of the energetic dynamism today. It is clear that more and more people love making things, love the connectedness with their materials, can express themselves through that relationship, and love the satisfaction that comes from seeing the fruits of their effort.