THE NEW AMERICAN LANDSCAPE

THE NEW AMERICAN LANDSCAPE

LEADING VOICES ON THE FUTURE OF SUSTAINABLE GARDENING

Edited by

THOMAS CHRISTOPHER

Copyright 2011 by Timber Press, Inc. All rights reserved.

All photographs are by the chapters lead author unless otherwise noted.

Grateful acknowledgment to the people who sustained us and made this book happen: Lorraine Anderson, Todd Forrest, Saxon Holt, Sally Widdowson, Matt Moynihan, Mollie and Moxie Firestone, David Kuester, Jess Kaufmann.

Frontispiece: Moynihan-Smith garden, Clayton, Missouri. Photo by John Greenlee.

Published in 2011 by Timber Press, Inc.

The Haseltine Building

133 S.W. Second Avenue, Suite 450

Portland, Oregon 97204-3527

www.timberpress.com

2 The Quadrant

135 Salusbury Road

London NW6 6RJ

www.timberpress.co.uk

Printed in China

Text designed by Susan Applegate

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The new American landscape: leading voices on the future of sustainable gardening/edited by Thomas Christopher.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60469-186-3

I. Sustainable horticultureUnited States. 2. Natural landscapingUnited States. 3. Organic gardeningUnited States. 4. GardeningEnvironmental aspects. I. Christopher, Thomas.

SB319.95.N49 2011

635.048dc22 2010034075

Catalog records for this book are available from the Library of Congress and the British Library.

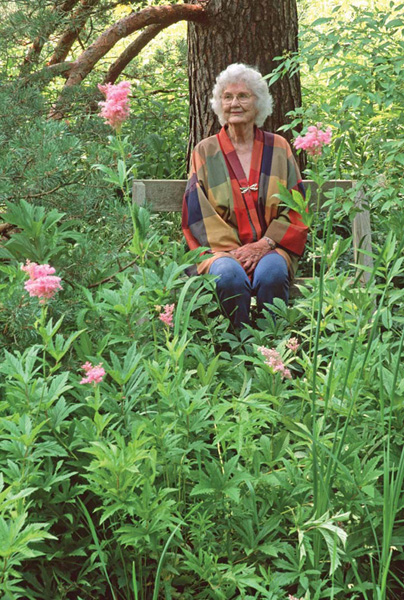

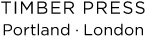

To Lorrie Otto

(19192010)

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1. Sustainable Solutions

by David Deardorff and Kathryn Wadsworth

CHAPTER 2. Managing the Home Landscape as a Sustainable Site

by the Sustainable Sites Initiative with Thomas Christopher

CHAPTER 3. The New American Meadow Garden

by John Greenlee with Neil Diboll

CHAPTER 4. Balancing Natives and Exotics in the Garden

by Rick Darke

CHAPTER 5. The Sustainable Edible Garden

by Eric Toensmeier

CHAPTER 6. Gardening Sustainably with a Changing Climate

by David W. Wolfe

CHAPTER 7. Waterwise Gardens

by Thomas Christopher

CHAPTER 8. Green Roofs in the Sustainable Residential Landscape

by Edmund C. Snodgrass and Linda McIntyre

CHAPTER 9. Flipping the Paradigm: Landscapes That Welcome Wildlife

by Douglas W. Tallamy

CHAPTER 10. Managing Soil Health

by Elaine R. Ingham

CHAPTER 11. Landscapes in the Image of Nature: Whole System Garden Design

by Toby Hemenway

INTRODUCTION

Queens of the prairie: Lorrie Otto and Filipendula rubra. Photo by Krischan Photography.

IVE NEVER MET A GARDENER whose aspirations werent constructive. We may differ passionately in what we find beautiful and appealing, yet one thing we all share. The desire to enrich the earth, at least our own small patch of it, to some degree motivates us all.

Thats our intention, but what we actually achieve is frequently far different. Too often, the way in which we nurture our plants depends on extravagant investments of limited or non-renewable resources, and massive inputs of fossil fuels. Instead of enhancing what we find in the landscape, we insist on making it conform to some artificial pattern. Indeed its a bizarre but prominent aspect of our horticultural heritage that we pride ourselves on imposing the exact opposite of what would naturally occur. We plant lawns in the desert and brag about the subtropical species we manage to nurse through northern winters, or the alpine flowers we have imprisoned in a lowland setting. We neglect the indigenous flora, insisting instead on importing exotic rarities that in our habitat rampage as weeds. So, beginning with a dream of lush fertility, we end up fostering environmental depletion and degradation.

It doesnt have to be this way. We can change our ways of gardening. By adopting more sustainable practices, we can make our plantings an environmental asset rather than a drain. They can become a haven for wildlife as well as people, and a reinforcement to the local ecosystem. In short, we can make our craft earth-friendly, as we have always imagined it should be.

This is a challenge, but its also an opportunity. Adopting these sustainable practices isnt about belt-tightening. Its about making our gardens more rewarding, more interesting and diverse than they have ever been before. Its a process of taking on the role of leaders, not just in our own backyards but in our communities as well.

The accepted definition of sustainability (to paraphrase Gro Harlem Brundtlandsee Defining Terms in ) is to meet present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs. Applied to gardening, this means using methods, technologies, and materials that dont deplete natural resources or cause lasting harm to natural systems.

This may seem like an obvious goal, especially since gardeners have all had first-hand experience of working with natural systems. Anyone who has ever raised their own vegetables, for example, knows what happens to the plot when you work it over a period of years without nourishing the soil. Or the unintended consequences that are likely to result from heavy-handed use of pesticides: chemically purging the garden of insects kills predators as well as pests, setting the stage for plagues and epidemics. Most of us have also seen how our gardens can benefit from respecting and working with nature rather than against it. We have experienced how feeding the soils microorganisms with organic matter in turn produces healthier, more vigorous plant growth, how selecting plants adapted to the local climate and soil makes success easy.

There are selfish benefits to be had from gardening sustainably. Gardening sustainably involves reducing not only inputs of resources (which saves money as well as the environment) but also inputs of energy. Much of the energy well conserve is the kind that comes out of an electrical wire or a gas pump, but well also be saving our personal energy, the push and pull of our own muscles. Gardening sustainably is, by definition, easier.

The environmental problems we now face are seemingly overwhelming in scope. This fosters a feeling of hopelessness and apathy: how can any one of us individually have an impact on the looming global water shortage, climate change, and the loss of biodiversity? If you look at statistics, though, it soon becomes clear that gardeners have an essential role in the answer to any of these crises, and that we can have a personal impact.

Reduced consumption of fossil fuels

The gardening style that has dominated the American landscape in recent decades involves an inordinate consumption of fossil fuels and is responsible for a disproportionate share of the pollutants released into the atmosphere every year. Curbing this appetite yard by yard can make a significant impact on resource depletion and air pollution, especially with respect to the release of greenhouse gases. The amount of gasoline we burn every weekend, mowing our lawns, could fuel 1.16 million cars and trucks for a full year of driving, according to recent Environmental Protection Agency estimates.

Next page