For the salmon of Devils Gulch,

so they may run again for my daughters children...

and those who come after.

I need to ask you a favor. After reading this book, please give it away. Youll know who its for: Your mother. Your neighbor. Perhaps the person sitting across from you at work. This book desperately needs you. It needs you because these other peoplethe real audience for this bookmay never buy it. They cant fathom the danger of living within an industrialized food system. For this reason alone, they need your help.

The intent of this book is simple. Seduce people with quirky collages and folksy handwritten notes that quietly introduce the tools to fix our crappy food system. The more people read, the more theyll remember. Ideas can be powerful like that.

So, the challenge remains. How do we get this book into other peoples hands?

Thats where you come in. Now that youve read these words, finish the rest of the book then tear out this page. Youll know what to do next. Let future readers remain oblivious to our silent pact. Thats how movements work. Our identities remain a mystery, but our convictions are strong enough to topple empires.

O ne of my clearest recurring childhood memories is that of spawning salmon. They ran up Devils Gulch, in Marin County, California, throwing themselves against the current, willing themselves over stones and flotsam-packed barriers of leaves and debris, onward past the limits of exhaustion, only to pause in deep pools, hidden beneath the oaks and towering redwoods lining the creeks steep banks, recharging in anticipation of yet another upstream surge. These salmon were here to spawn, lay eggs, then die. This struggle of animal against nature was a yearly childhood event, one that connected me, even as a young boy, to the mysterious natural world around me.

Decades later, I was justifiably excited to share this experience with my own daughter. When February came, my wife and I bundled her in a coat, scarf, and mud boots, and hiked the trail leading up from Lagunitas Creek to Devils Gulch.

The salmon werent there.

As I would later learn, this spawning ground had collapsed years before. Theories abounded. Overfishing. A golf course built beside a nearby stream. Runoff from a hillside housing project. No one knew for sure.

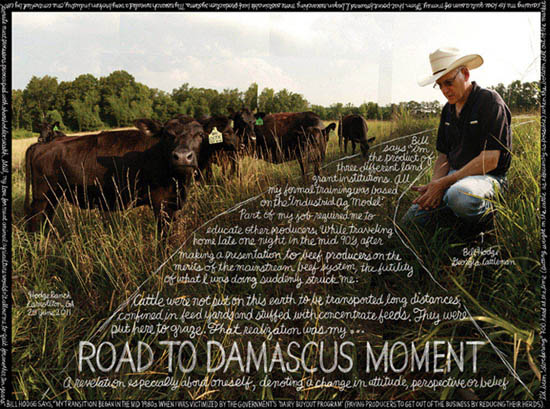

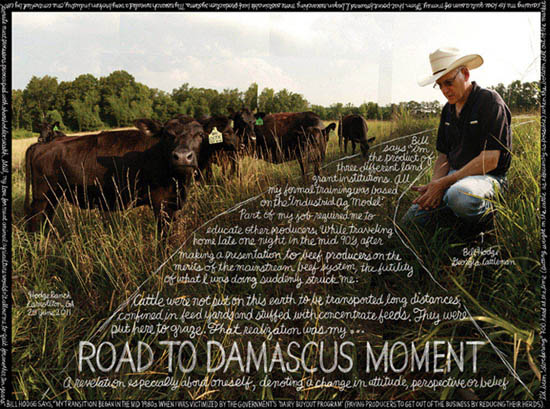

I never properly cataloged that disheartening winter afternoon until two years later, when I stood in a Georgia hay field talking about grass-fed cattle and the vagaries of summer rain with Bill Hodge, an earnest, calmly focused cattleman who ultimately turned our conversationas often happens in these partsto the Bible. In the years after Jesus was crucified in Jerusalem, Saul of Tarsus swore to wipe out the newly formed Christian church. He set off for Damascus armed with a letter from a high priest authorizing the arrest of any new followers. After a blinding light struck down Saul and his companions in mid-journey, a voice spoke, one only Saul could hear. Its message triggered a series of events that ultimately led to his religious conversion. It was the first Road to Damascus moment. Hodges own came ten years ago.

B ack in the 1980s, Hodge was victimized by the governments dairy buyout program, which paid dairy producers to get out of the business by reducing their herds. He accepted their offer and began stockering his herdputting weight on the cattle as quickly and economically as possiblewhen the bottom suddenly fell out of the market. He lost nearly seven hundred head. An industry hed never questioned had failed him.

He thought about doing something else, but his love for meat animal agriculture was simply too great, so he ended up working in producer education for the local land grant institution. Ironically, part of his responsibilities included teaching cattlemen how to work within the big corporate meat processor model.

I was traveling home late one night, after making a presentation to beef producers on the merits of the mainstream beef system, Hodge recounted, and thats when the futility of what I was doing suddenly struck me. Cattle were not put on this earth to be transported long distances, confined in feed yards, and stuffed with concentrate feeds. They were put here to graze. That was my Road to Damascus moment.

W hat happened to the Devils Gulch salmon of my childhood? How many other people, folks just like me, have their own childhood stories of close encounters with a natural world that has since vanished?

We are living within the Great Changeits happening at this momentbut the shift isnt sudden. It wont startle us into action. This is a gradual change. A creeping change, imperceptible from one day to the next. Its industrial, technological, and dehumanizing. We cant see the Great Change because it lacks immediacy; we tend to forget its happening. The witnesses to these before and afters in the natural world, the people who still remember the Way Things Used to Be, are disappearing, dying off. The amazing salmon runs of my childhood are gone from Devils Gulch. That winter morning, as I attempted, without success, to show my five-year-old daughter precisely what she wasnt seeing in that creek, I had my own Road to Damascus moment.

I want to bring those salmon back. I want my daughter to share these memories, to understand the complexity of things, to one day restore the natural order to Devils Gulch. To do that shell need to understand the meaning and function of all those moving parts, the nameless pieces powering this modern industrial apparatus weve created.

Weve all had Devils Gulch moments. Weve all felt powerless when confronted by systems composed of parts we depend on yet dont understand.

This is a book about first understanding, then dismantling, our industrial food system.

Can the way it is be reexamined, its offending parts held up to the light, observed, and discarded?

Our food system is opaque, composed of nameless objects. Deciphering their meanings will require mastering a new language, which can be learned one word at a time.

We live in a world of dwindling natural resources, but the principle of SUSTAINABILITY offers us a road map for managing what we have left. Yet as we attempt to put our world back in balance, weve seen the term sustainability grossly misused, its meaning devalued, hijacked, turned into hollow-sounding marketing jingles.

The stakes are high. If people dont understand the meaning (and implication) of terms like FOOD MILES , CARBON FOOTPRINT , CSA , ORGANIC , FOOD SECURITY , FOOD DESERT , GMO , GRASS-FED , DIRECT TRADE , or even PASTURE-RAISED , how can they live more sustainably?

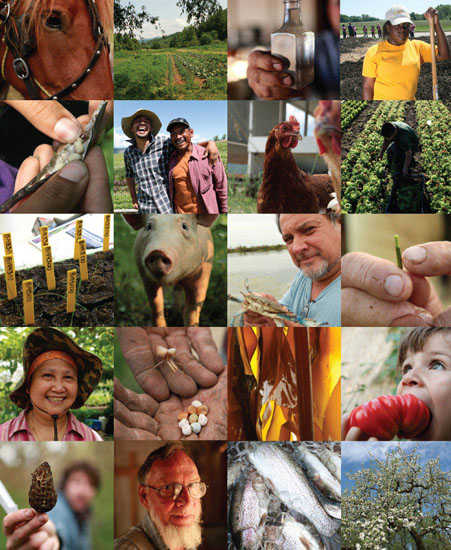

To help take back the meanings of these important ideas, I set out to document the work of two hundred thought leaders, architects of a new vocabulary reflecting the most promising solutions for creating a vital and sustainable food system in this country. I asked each of them for a single term that defined the essence of their work, because words are truly the building blocks for new ideas. I feel like Ive only captured a fragment of this veritable reimagining not only of American agriculture, but of our countrys consumer culture, one defined by excess and disposabilitybut now one showing signs of responsibility, of resilience, and even of hope.