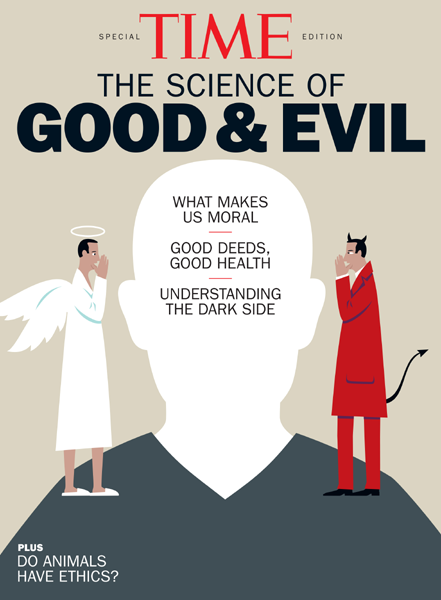

THE SCIENCE OF GOOD & EVIL

THE SCIENCE OF GOOD & EVIL

There is much in the human spirit to love, and there is much to fear. That is the riddle of us

BY JEFFREY KLUGER

Nature ought to have washed its hands of us by now, and if it hasnt yet, every day seems to give it a new opportunity to rethink that decision. Its not just that were evilthough we are. We build bombs, we manufacture guns, we slaughter one another with an ugly lustiness that defies the powerful social impulses that are supposed to be coded into us.

The bigger problem for nature is that were also fools. If our genes have told us once, theyve told us a thousand times: stay out of harms way. When a madmans raging, when a bomb goes off, when a 110-story building is pancaking down and another one right next to it is about to do the same, run the hell away. Yes, yes, you hear a lot about fight-or-flight, but really, you want to live? Go for flight. And yet we dontor at least some of us dont.

Consider one of the more conspicuous examples of human savagery in the past several years: the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, in which a happy exercise in play and pageantry was ripped apart by sudden violence. The bombs went off, the victims fell, the familiar footprint of flesh and blood and terror was stamped into the streets. And people did what they are hardwired to do, which is that they scatteredat first.

And then an equally familiar gathering began. Police and military teams swarmed the snow fences along the streets, pulling them down to allow medical personnel in. Doctors, paramedics and passersby knelt in the blood to administer aid to people they had never met before that moment and might never see after it. Perhaps there were more bombs still to go off; perhaps the same madmen who set off the first ones would show up with assault weapons next. Never mind; the caregivers rushed in anyway.

There has always been this kind of opposing physics to good and evil. Evil begins from a point sourcea cartridge of gunpowder, a nugget of uranium, a knot of hate in a single dark mindand then it blows outward. Good gathers from everywhere around the blast and then movesfoolishly, perilously, wonderfullytoward it.

Sometimes we actually have to fight for the opportunity to risk our lives this way. The police were trying to keep us back, but I told them I was a physician and they let me through, Natalie Stavas, a runner in the marathon, told the New York Times in the aftermath of the bombing. At one point, her ministrations included performing CPR on a woman whom she suspected was already dead. Consider the exchange rate of that transaction: her own very much extant life placed at risk for one that may have been past saving.

Ethicists, anthropologists and evolutionary biologists have tried for a long time to figure out why we do these thingsputting ourselves in mortal danger to save other people and, in so doing, defying our one great evolutionary imperative, which is to stay alive ourselves. There are the reductionist explanations, of course. Its genetic mathematics, say the sociobiologists. You wont help anyone at all, just the ones with whom you have some biological connection. Youre twice as likely to come to the aid of your parents, siblings and children, with whom you share 50% of your genes, as you are to help your grandparents, grandchildren, nieces and nephews, with whom you share 25%.

Things move on down this way in tidy arithmetical lockstep through your cousins and great-half-aunts and great-great-great-uncles, with their 12.5% and 6.25% and 3.13% relatedness, and it all makes a perfect kind of orderly sense, until you ask why youd consider helping the bleeding stranger on the Boston streets, with whom you share no genes at all. At that point the sociobiologists start a lot of hand-waving about tribal relatedness and collective genetics and you pretty much stop listening.

In the alternative, there are neurological explanations for human selflessness. Were sympathetic creatures, but not in the prettified way we usually use that word. Our brains are wired with mirror neuronscells that make us mimic the behavior of the people around us, so that we laugh when they laugh, cry when they cry, yawn when they yawn. We even wince at other peoples pain. That provides social cohesion, but it also reduces our most generous impulses to something more transactional: we relieve the suffering of strangers in part because it hurts too much to do nothing.

A similar reductionist argument is made by scientists who scan the brain and actually see where goodness lives. Moral behavior is processed in the prefrontal cortex and the meso-limbic region. It follows a very mappable neuronal path that is no more complex than the one that allows you to throw a baseball or write your name, and thats no more lyrical either.

And yet these answers just ring wrong. You can deconstruct a painting by explaining the salts and sulfides that make up its pigments; you can parse a symphony by measuring the frequency of the final crashing chord, but youre missing something bigger.

Humans, instead, are guided by a sort of moral grammara primal ethical structure on which decency is built, just the way our language is built, on syntax and tenses and conditional clauses. You know when a sentence is right and when it isnt even if you cant quite explain why, and you know the same thing about goodness too.

It starts young. Toddlers seem like domestic anarchists, and yet they are strangely self-policing. They exhibit little evident guilt when theyre caught, say, stealing a cookie. Any regret is more about the rotten luck of getting busted. But theres a push-pull when the same toddler hits a little sibling who then dissolves in tears. You see it in the sympathetic expression, in a worried twisting of hands, in, often as not, an attempt to give comfort immediately after giving pain. The cookie theft was a broken rule. The hitting was a basic wrong.

What starts young stays with us. Yes, were savage; yes, were brutal. The people who set the Boston bombsor shoot up high schools and nightclubs, or drive a car into a crowd of people protesting white supremacistsare humans like anyone else and thus close kin to us all. But were close kin, too, to the first responders; were close kin to the people who cried for the first-graders killed at Sandy Hook Elementary school in 2012, even not knowing any of them personally, because first-graders simply shouldnt die.

The very empathy that brings us to those tears need not be wasted on the people who commit the crimes. In 2001, when the rubble of the September 11 attacks was still smoldering, TIMEs Lance Morrow wrote, Anyone who does not loathe the people who did these things, and the people who cheer them on, is too philosophical for decent company.

But its equally true that the people who commit such crimes are, in many ways, the free radicals of our social organismthe atoms that go bouncing about, unbonded to anything, doing damage to whatever they touch. The bonds they lack are the ones the rest of us sharethe ones that make us pull away the snow fences and kneel in the blood pools. Theres terrible pain in thatand profound love too.

Next page