Shire Publications,

part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK

1385 Broadway, 5th Floor, New York, NY 10018, USA

Email: shire@shirebooks.co.uk

Website: www.shirebooks.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Conway

First ebook edition 2012

This electronic edition published in Great Britain in 2018 by Shire Publications

Produced and conceived by Rupert Wheeler

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data:

A CIP record of this title is available on request from the British Library

Print ISBN: 9781784423360

Ebook ISBN: 9781784423346

Publishers Note.

In this facsimile edition, references to material not included in the selected extract have been removed to avoid confusion, unless they are an integral part of a sentence. In these instances the note [not included here] has been added.

INTRODUCTION

After 28 years of retirement following 42 years service with the London & North Eastern Railway and British Railways, I find myself studying a text that takes me back to the Victorian era and then forward to the LNER Rule Book (1933) that reigned supreme when I started as an apprentice at Doncaster in January 1941. The Editor has chosen well from a large selection of instruction booklets and the task I have set myself is to relate some of the fascinating points raised within this book to my own practical railway life of a slightly later era.

Maurice Vaughan was a GWR engine driver writing from Plymouth in 1893, a year after the Broad Gauge ceased to exist. He writes of the Mutual Improvement Class formed to train the young engineman and such classes were still going strong with the same name up to the end of steam in 1968. But they were always voluntary and although management took a helpful and practical interest, there was no formal training other than profound experience, which made our enginemen such great individualists. Certainly advice and instruction on the job from an Inspector or a Shedmaster helped with the countless lessons to be learned, but formal classroom and workshop experience only arrived with the diesels and electrics.

Vaughan would have been an engineman before the days of the continuous vacuum brake, where every wheel on the train as well as the engine was braked when the driver stopped at a station. But he wrote in 1893 that if the vacuum ejector fails, the driver would inform the guard and work the train forward with the hand-brake. This would mean the fireman and guard working in unison on their hand-brakes, not so comfortable and never to be countenanced today. But it did me good to read of the practice, or it once happened to me with the Westinghouse air brake when the air pump refused duty and at our first call at Clapton, we just managed to stop at the far end of the platform. We knew there was an express due four minutes behind us and that if we hung about, we would delay him. A quick word with the good old guard to ask him to do his stuff on his handbrake, a word to the porter to ring the Wood St depot foreman and off we went hell for leather onto the Chingford branch. We got to Wood St where Jack Barker was waiting with his tools and without further ado he went to the front of the engine to attend to the pump, hanging on with one hand while we climbed the bank up to Chingford. No reports made, no hesitation nor argument we simply went about our duty to run to time. Jack soon had the pump in order, and of course all the men would have done exactly the same even if I, as District Motive Power Supt., had not been there I would simply never have heard about it! All through this book you will feel as you read that you are amongst practical men, all members of the Great Brotherhood of Railwaymen to which I am still proud to belong.

I believe that Michael Reynolds was a Locomotive Inspector on the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway when he wrote the early editions of Locomotive Engine-Driving, much enhanced by detailed drawings of the famous Stroudley single-wheeler Grosvenor which was built in 1874. It had wooden brake blocks and a powerful steam brake but the LB&SCR had yet to adopt the excellent Westinghouse brake effective throughout the train. For all that, he still used the Grosvenor and the same drawings long after the continuous brake had been introduced. The Westinghouse brake was a joy to operate once you learned to put your faith in that little brake valve which was grasped so comfortably in the hand. One application of 15psi of air was sufficient to make a brisk and perfect stop in the right place once you had the confidence and experience.

Reynolds felt strongly that certificates of proficiency should be introduced to be rigorously earned and to recognise true ability as a means not only of raising the standard of the craft but to enhance the social standing of both driver and fireman. His discourse on the art of engine-driving and of firing is complete and he makes the point that firing is as much of an art as driving, but that the driver is in charge and carries the ultimate responsibility for all that takes place in that private world of the footplate.

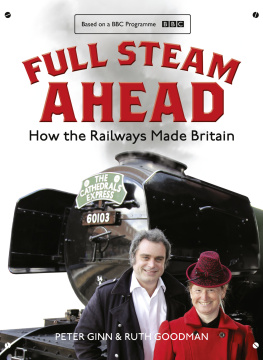

The author on the left with Bryan Gibson, an ex BR colleague, on a LMS Class 2 Ivatt 6441 at Amersham. They were taking part in Steam on the Met in 1993.

Some of Reynolds advice is clearly of its time. For example, he says firmly that no driver must run before time, but I would remind him of the beloved odd minute or two kept up the sleeve by most enginemen. He also says that drivers must not shut the regulator before notching up with the reversing lever. That may have been the case with the Brighton engines, but the best way to get a rupture was to try it on a GN slide valve engine: you could put your foot on that little footrest and haul with legs apart with all your strength but that lever would not budge and no driver that I ever knew would try it on! But elsewhere there are also pertinent points of interest that came down the years to the end of BR steam.

H. A. Ivatt was the Locomotive Engineer of the Great Northern Railway and his little booklet was intended largely for the younger, relatively inexperienced men. It is a clear, friendly and uncluttered work that explains in simple terms how the job should be done. In paragraph 85, Ivatt generously tells the fireman how to get out of trouble when stopped short of steam. In fact, I never heard of this method being put to the test on the rare occasions that we ran short of steam with Ivatts very free-steaming tank engines on the Bradford expresses. One could reach Morley on time and then get gassed up in three or four minutes with enough steam and water in the boiler to face the climb up to and over the top onto Adwalton Moor. I wouldnt fancy dropping down into Bradford with anything but a brake in prime order!

One rarely reads about picking up water at speed but there is a fair amount to learn from our old friend experience. Driver Bill Thompson and I worked a heavy stopping train from Doncaster to Grantham with one of Mr Ivatts Atlantics, 4401, a grand engine. Now Bill was a generous man who usually came to work with his pockets stuffed with fruit and as we got near to Muskham troughs, he said: Now, Richard, well get a drop of water at the Trawvs but dont pull the lever down until I shout. We approached at about 50 mph and I stood at the lever very much at the ready. We ran on to the troughs; on and on and I waited and waited until I felt that Bill must have forgotten, so I pulled the lever. Bill turned his kindly if quizzical face towards me as the lever locked solid and the tank overflowed, the water (and coal) cascading down onto the footplate until there was nowhere to stand and we got a good soaking. As I slaved away at clearing up, a wiser young man, Bill said: Never mind, Richard, youll know better next time have another apple! This was one that wasnt in Mr Ivatts splendid little book.