By the same author:

Matrix and line:

Derrida and the possibilities of postmodern social theory

Humanism and its aftermath:

The shared fate of deconstruction and politics

Politics in the impasse:

Explorations in postsecular social theory

music of Yes:

structure and vision in progressive rock

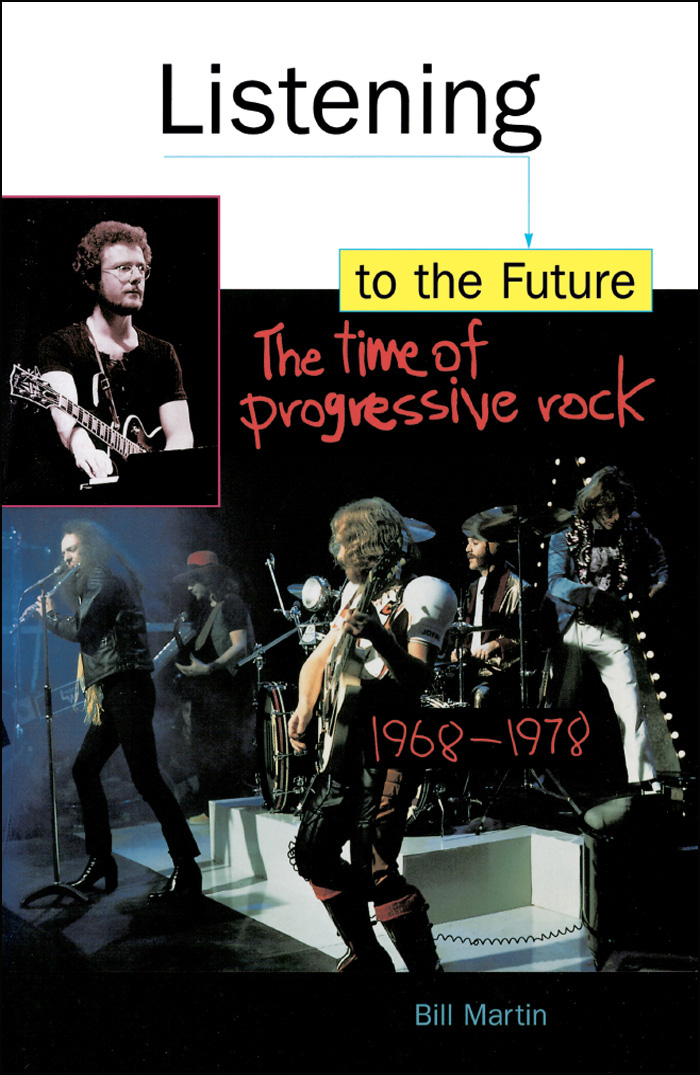

Photo of Robert Fripp courtesy S. Morley/Redferns.

Photo of Jethro Tull courtesy David Redfern/Redferns.

Copyright 1998 by Carus Publishing Company

First printing 1998

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, Open Court Publishing Company, A division of Carus Publishing Company, 315 Fifth Street, P.O. Box 300, Peru, Illinois 61354-0300.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Martin, Bill, 1956

Listening to the future: the time of progressive rock, 1968-1978/Bill Martin.

p. cm.(Feedback: v. 2)

Includes discography, bibliographical references, and index.

ISBN 978-0-81269-944-9

1. Progressive rock musicHistory and criticism. I. Title. II. Series: Feedback (Chicago, Ill.); v. 2.

ML3534.M412 1998

781.66dc21

97-36495

CIP

MN

To order books from Open Court, call toll-free 1-800-815-2280.

This book has been reproduced in a print-on-demand format from the 1998 Open Court printing.

Open Court Publishing Company is a division of Carus Publishing Company.

For my mother and father,

Eve and Gene Martin

The past carries with it a temporal index by which it is referred to redemption. There is a secret agreement between past generations and the present one. Our coming was expected on earth. Like every generation that preceeded us, we have been endowed with a weak Messianic power, a power to which the past has a claim. That claim cannot be settled cheaply.

A chronicler who recites events without distinguishing between major and minor ones acts in accordance with the following truth: nothing that has ever happened should be regarded as lost for history. To be sure, only a redeemed humankind receives the fullness of its pastwhich is to say, only for a redeemed humankind has its past become citable in all its moments. Each moment it has lived becomes a citation lordre du jourand that day is Judgment Day.

The soothsayers who found out from time what it had in store certainly did not experience time as either homogenous or empty. Anyone who keeps this in mind will perhaps get an idea of how past times were experienced in remembrancenamely, just in the same way. We know that the Israelites were prohibited from investigating the future. The Torah and the prayers instruct them in remembrance, however. This stripped the future of its magic, to which all those succumb who turn to the soothsayers for enlightenment. This does not imply, however, that for the Israelites the future turned into homogenous, empty time. For every second of time was the strait gate through which the Messiah might enter.

Walter Benjamin, from Theses on the Philosophy of History

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

As with my earlier music of Yes, Listening to the future was also written as a labor of love. I want to offer heartfelt thanks to everyone who helped with this project. This includes a rather long list of friends both old and new, who shared with me their ideas about musicsometimes without knowing it: Jim Abraham, Alison Brown, Kevin Condatore, Al Cinelli, Billy Chapman, John Covach, Andrew Cutrofello, John Collinge, Glen Di Crocco, Jim DeRogatis, Martin Donougho, David Detmer, Sarah Dowless, Zane Edge, Lydia Eloff, Nina Frankel, Aaron Fichtelburg, Henry Frame, Miller Francis, Diana Fuss, Stephen Gardner, Mark Giordano, Tom Greif, Brett Gover, Lewis Gordon, Peter Gunther, Stephen Houlgate, Patricia Huntington, Craig Hanks, Christine Holz, Joanie Jurysta James, Leslie Jones, Tony Kirven, Nick Kokoshis, Dana Lawrence, Michael Lind, Raymond Lotta, Chris Mitchell, Tina McRee, Brad Merriman, Edward Macan, Brenda MacDonald, Lisa Mikita, Innes Mitchell, Sam Martin, John Martin, Lynne Margolies, Thomas and Coral Mosbo, Clay Morgan, Todd May, Martin Matustik, Kate Murphy, David Orsini, Jeff Rice, Garry Rindfuss, Jane Scarpontoni, Dale Smoak, Chelsea Snelgrove, Gary Shapiro, Catrina Thundercloud, George Trey, Jerry Wallulis, Cynthia Willett, Deena Weinstein, and Robert Young.

For their friendship and encouragement, I would like to thank my colleagues in the philosophy department at DePaul University: Ken Alpern, Peg Birmingham, Cindy Kaffen, Daryl Koehn, David Krell, Niklaus Largier, Mary Jeanne Larrabee, Will McNeil, Darrell Moore, Michael Naas, Angelica Nuzzo, David Pellauer, and Katherine Rudolph.

Thanks to the people at Open Court Publishing for their support of this project, especially my ever-patient editor, Kerri Mommer.

I have the great fortune to be married to the African Japanese queen of Kansas, Bascenji. Thanks, my Yoko and SdB, my dear Kathleen, standing by your vinegar boy and guttersnipe even under conditions of dark existentialism.

Finally, for giving me life and for giving me much in life, this book is dedicated to my parents, Eve and Gene Martin.

A funny thing happened on the way to the forum. About a year-and-a-half ago, I felt sure that I was coming to the end of writing the first book-length study of the music of Yes. Then it came to my attention that a fellow Yesologist named Thomas Mosbo had just published a book on the group, Yes, but what does it all mean? Still, finishing music of Yes in the late spring of 1996 (the book came out in October of that year), and turning to the writing of the book you are reading now, I gave in once more to a feeling of certainty, namely to the idea that I was writing the first intellectually oriented study of the larger field of progressive rock.

Foiled again! Indeed, at a bookstore party for the release of music of Yes, my graduate assistant, Aaron Fichtelberg, came up to me and said, Hey, have you seen this? He was holding Edward Macans Rocking the Classics. As many readers will know, the book features a concert photograph of Yes on its cover. Zeitgeist or what? As a matter of fact, I fervently hope so.

About six months later, as I was entering into the final stages of writing this book, I happen to see an advertisement in The Wire. (This is an English magazine, by the way, that often attacks progressive rock in terms that, by now, are all too well known to readers. Well, The Wire and other nemeses of progressive receive some well-deserved lashings in what follows.) I purchased that particular issue of the magazine to read an interview with Chris Cutler, percussionist and composer with Henry Cowone of the greats, in my view. (The interview is discussed in chapter 3.) Then what should I come across but an advert for yet another book on progressive rock, Paul Stumps