Copyright 2003 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acidfree paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 191044011

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Newman, Simon P. (Simon Peter), 1960-

Embodied history : the lives of the poor in early Philadelphia / Simon P. Newman.

p. cm. (Early American studies)

ISBN 0-8122-3731-5 (cloth : alk. paper). ISBN 0-8122-1848-5 (pbk. : alk paper)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. PoorPennsylvaniaPhiladelphiaHistory18th century. 2. PoorPennsylvaniaPhiladelphiaHistory19th century. 3. Public welfarePennsylvaniaPhiladelphiaHistory18th century. 4. Public welfarePennsylvaniaPhiladelphiaHistory19th century. 5. Philadelphia (Pa.)Social conditions18th century. 6. Philadelphia (Pa.)Social conditions19th century. 7. Philadelphia (Pa.)Economic conditions18th century. 8. Philadelphia (Pa.)Economic conditions19th century. 9. Philadelphia (Pa.)PopulationHistory18th century. 10. Philadelphia (Pa.)PopulationHistory19th century.

HV4046.P5 N48 2003

305.5'69'097481109033dc21

2003042615

Introduction

Early national Philadelphia was a large, populous & beautiful city regular and well built, filled with wide and straight streets flanked by trees. To citizens and visitors alike, this metropolis of the United States appeared to be the nations finest town, and the best built.).

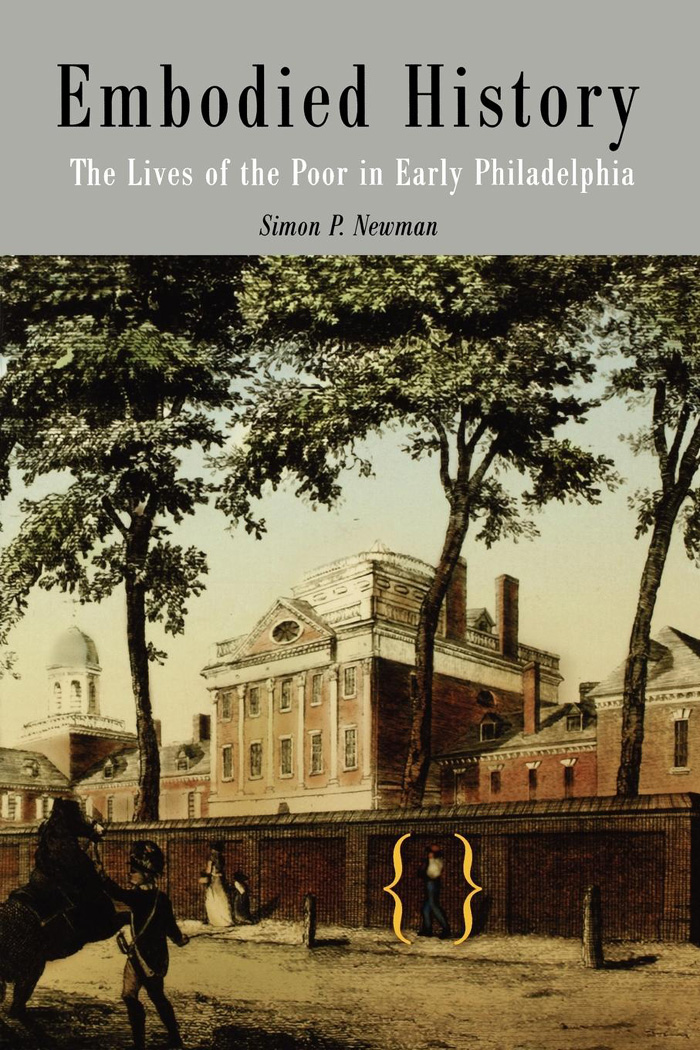

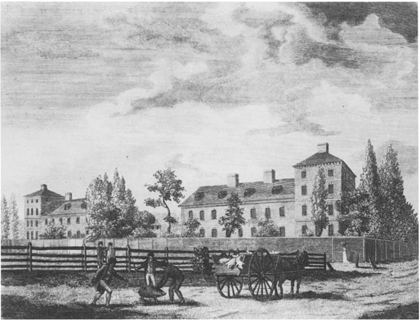

Conspicuously absent from these engravings and from many contemporary descriptions are Philadelphias poorer residents. Even Birchs renderings of such buildings as the almshouse or the Pennsylvania Hospital, structures designed for the citys poor, seem positively bucolic, and the very Philadelphians for whom these institutions were intended are nowhere to be seen (). For all its unusually wide streets, early national Philadelphia was teeming with people, and many of them looked very different from the finely dressed young men and ladies who strolled along the streets of Birchs imagined city.

As fast as the colonial town developed into a thriving and populous city of commerce, manufacturing, and trade, so too grew urban poverty. In stark contrast to Birchs prints were the words of those men and women of wealth and power who felt themselves surrounded and increasingly threatened by the children, dogs and hogs who swarmed through the streets; the dissipated men, and idle women who filled the ). However, Birchs prints were not flawed attempts to portray the reality of early national urban life, but rather idealized images of Philadelphia as the citys elite might have wished it to appear, as a place in which the troublesome poor were neither seen nor heard but rather controlled by and confined within civic institutions.

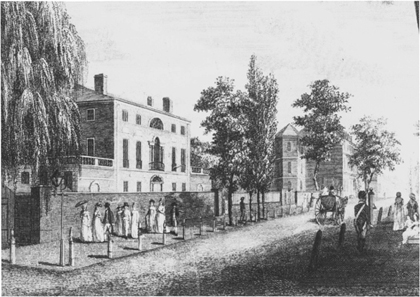

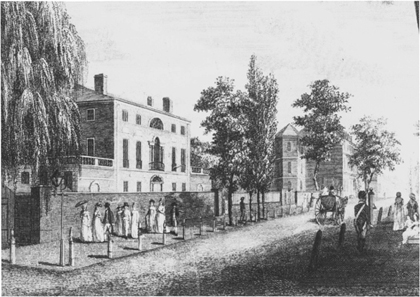

Figure 1. William Birch, View in Third Street from Spruce Street, Philadelphia, 1800. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia. The handsome Federal style mansion dominating this view was built in 1789 by William Bingham, a wealthy merchant, banker, and legislator. Set amid extensive formal gardens, William and Anne Binghams home was the preeminent center of elite social life in early national Philadelphia.

Impoverished Philadelphians were readily identifiable, for their appearance contrasted sharply with that of their more affluent neighbors. Periods of un- or underemployment and low wages took physical form in undernourished, undersized, and poorly clad bodies, which were far The former constituted the deserving poor, who, by demonstrating a willingness to work and by exhibiting an acceptance of their lot through respect, civility, and deference in their dealings with their betters, claimed a right to the support of the community. In contrast, the thriftless poor appeared dangerously disrespectful and subversive; they were held responsible for their condition and as a result were judged to be undeserving of aid and the objects of just punishment.

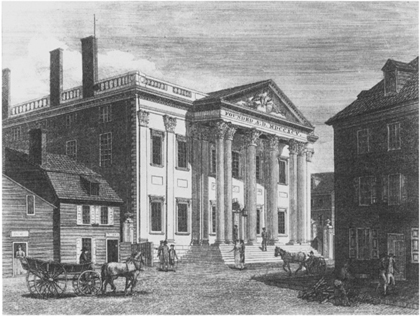

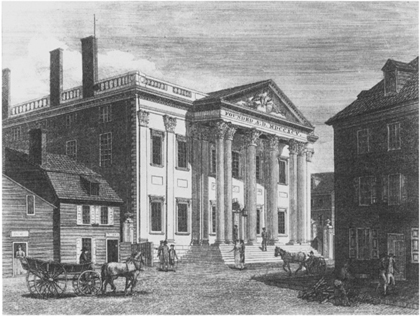

Figure 2. William Birch, Bank of the United States in Third Street, Philadelphia, 1799. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia. Adjacent to Dock Street and between the waterfront and the Walnut Street Jail, this was the heart of the city. In the alleys behind and around these buildings lived the citys lower sort, yet in presenting this image of the power and promise of the new nation and its government, Birch again neglected to include any but a handful of respectable men and women, and even fewer respectable working men.

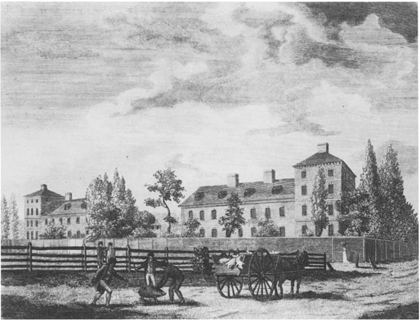

Figure 3. William Birch, Alms House in Spruce Street, Philadelphia, 1799. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia. Several hundred yards from Independence Hall, Pennsylvania Hospital, and Walnut Street Jail lay another of the citys great buildings, the Alms House. Designed as a place for the incarceration, correction, and betterment of the bodies of deserving and undeserving poor alike, the almshouse was for and about poor bodies, yet it appears here without any such bodies in evidence. Instead, it is a scene of bucolic delight in which a farmer heading to market attempts to capture an escaped pig.

Trade, population, and wealth inequality all grew rapidly in the cities of post-revolutionary America, and as the ranks of the poor increased a simplified discourse of sorts of people replaced the rhetoric of a complicated hierarchy of orders and estates, blurring distinctions between the deserving and undeserving poor.

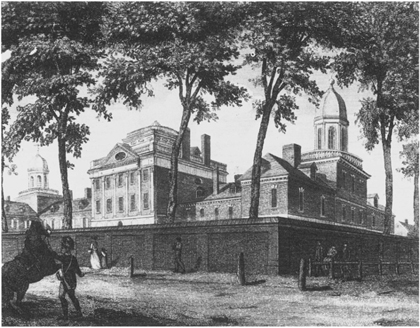

Figure 4. William Birch, Pennsylvania Hospital in Pine Street, Philadelphia, 1799. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia. Although the hospital was intended for the sick and injured bodies of the deserving poor, this engraving excludes images of such folk, despite the fact that many lived in the streets around the impressive building.